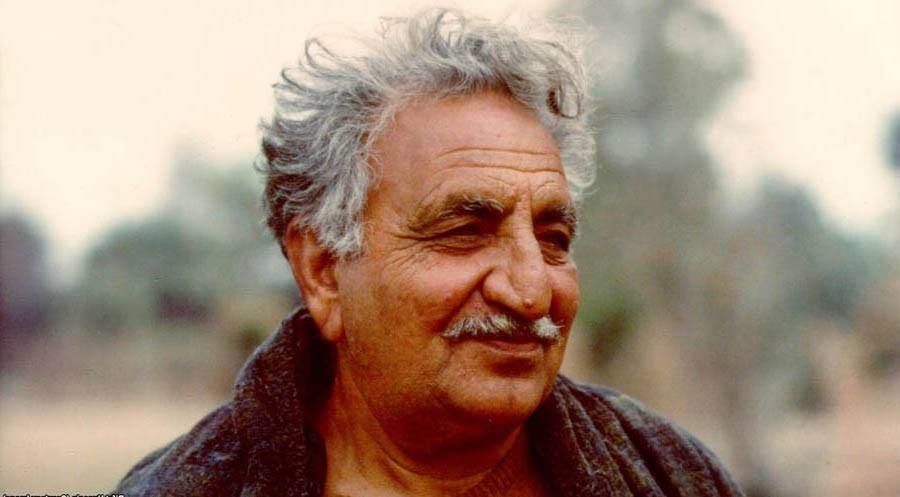

This is not a biography of Ghani Khan. It’s only a montage of stories of and about him

To write about a poet’s life is difficult. It is difficult because when gods speak, they speak through poetry. The mortal poet writes the words and dies, but the immortality of gods transcends, remains and shines through poetry. A poet is a chosen one. As Ghalib said, "sareer-e-khama nawa-e-sarosh hai" (the scratching of the quill is the voice of angel of paradise). Ghani Khan was one such medium whom the gods chose to write immortality on paper. This is his story.

My source on the great poet is a long conversation with Raheel Siddiqi, an admirer of the great poet Ghani Khan. Neither of us speaks the language of poetry but we have learnt a lot about the man.

He was the first-born son of great political leader of Pakistan’s frontier areas, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, who created the Khudai Khidmatgar movement. Much has been written about him so there is no need to delve into that episode of political history.

Ghani Khan ran away from home at the age of 16. In those days of United India, the trains chugged all through the country from the West to East. His train departed on a winter morning from Peshawar Cantonment Station, which still stands majestic. The steam, the whistle, the scrambling of passengers and a 16-year-old boy trying to get on the train, scared but determined to pursue a dream of becoming a painter.

I would like to imagine that he had heard about the school in Calcutta through his father’s friends from Indian National Congress, Shanti Niketan, founded by Rabindranath Tagore. Among other things that Tagore wrote, he wrote a beautiful short story ‘Kabuliwala’, which was filmed later with Balraj Sahni in the lead role. I imagine that Tagore got his inspiration from Ghani Khan although the times do not coincide but the characterisation of ‘Kabuliwala’ is inspirational and depicts a beautiful and humane soul. Sometimes we know a man before we even meet him; one of the oddities of life.

The 16-year-old entered the town of Shanti Niketan and started the pursuit of his passion at the Visva-Bharati University. He was good at what he did and he kept becoming better. Passion is a curious thing. It does not come as a singularity. It is a whole, rather a wholesome package. It is all consuming. It shines through all things you do. It cannot be that passion for one thing does not spill over to other things.

While educating himself, the poet fell in love with a girl from Hyderabad Deccan. The love must have been rewarding and must have awakened the poet in Ghani Khan; until she walked into his life, he was only an artist.

However, this bliss ended soon. The patriarch Abdul Ghaffar Khan despite his leftist politics was a Pakhtun and a staunch Muslim. The moment he learnt about his son’s interests, he took the next morning train to Calcutta as his son had done a few years ago. He forcibly took his son out of the greatest art school in India and placed him in the greatest madrassa of India -- Dar-ul-Aloom Deoband.

The ever-dutiful son, Ghani Khan, the painter and the poet, started his studies at Deoband, dutifully graduating from there.

A paternal order and a son’s respect for it is a trait rare in poets and artists. It is a strange thing that the greatest love poet of Pashtu language was a madrassa graduate.

He kept his promise to his love. After graduating, he went to Hyderabad and married the love of his life. He brought his bride from the South of India to a small town in Frontier -- Charsadda. Ghani Khan also espoused the political cause of his father. He spent his time in Pakistani jails from 1948-1954, led the political movement and had followers. His father somehow had not forgotten his rebellion of passion, so he named his younger brother Wali Khan as his political successor in a political meeting. The poet walked out of that meeting and politics forever.

I must clarify here that this story of the poet is not a biographical account; it is a montage of stories of and about him. The persona will be pieced together like beads on a string, one story by one.

He used to make wine using his own grapes, wrote poetry and painted away for the rest of his life. He kept his wine in big earthen pots or maybe wooden vessels. These vessels were left to ferment in a locked shed out in the garden of his home. Once it happened that the door of the shed remained unlocked. A donkey just roamed in and looking for shade entered the unlocked wine shed. I am sure the donkey was thirsty so he drank from the vessels of wine, not realising what it was that he was drinking. He drank the sweet drink and felt its effects.

Soon, the servants discovered what had happened. They were mortified as Khan would be enraged to know that his season’s wine was in the belly of a donkey. Reluctantly, they informed him.

The poet came out and saw what had happened. The poor donkey was lying on the floor, occasionally trying to get up on wobbly legs and falling down again. Instead of mourning the loss of his precious wine, the poet started laughing and said, "You ass, you proved to be an ass. If it were Ghani Khan in your place, he would have stood after drinking a barrel of wine". He walked away laughing, with instructions not to harm the poor beast and let him lie there till he was able to walk away.

This is one bead in the string of our stories about the poet.

Another story was related to my friend by someone who had visited the poet while he was on his death bed. It’s better to hear it first-hand.

"I went to Ghani Baba’s home to pay my respect. I was nervous as a Masters student should be whilst being ushered to the bedroom of the greatest poet alive in Pashtu language. He was lying, weakened by his ailment. I sat down beside his bed and exchanged pleasantries and prayers. I glanced around the room. It was a simple room adorned with his paintings and some photographs. I could not help glancing at his bedside table. There was a framed photograph of the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. Realising she must be someone from the family, I felt a sense of guilt and must have blushed too. As I forcefully turned my gaze away, Ghani Baba saw it. I heard him chuckle, ‘Isn’t she beautiful?’ I was dumbstruck as if caught in an act. ‘I know she is. She is my wife. If you want the photograph, you can take it. A thing of beauty should not be kept in veils.’ I was ashamed beyond redemption but the poet assured me that he meant what he had said. I came out with a heart full of shame and admiration for the man who did not want to possess beauty."

Another bead was then added to our string.

Ghani Khan had only one son. As the story goes, his son was roaming in the garden when he saw the gardener boy was not paying any attention to flowers nor was there a proper pruning of hedges. He knew his father loved his garden. The gardener boy happened to be a Mohmand from the tribal agency and had grown up in that very house since he was a child. He must have been a second generation servant.

The poet’s only son got angry as was his due because the boy was not doing his job well. The clash of words turned nasty and the poet’s only son abused him verbally. The gardener boy got so angry that he hit the poet’s only son with a spade many times, killing him there and then. People came running but it was too late.

The poet was informed about this tragedy. He told the people not to call the police or harm the boy. He would himself decide in the evening. He came out in the evening. The boy was in chains and sitting on the floor with guards all around. It was expected the Khan would himself shoot the boy or order his killing as is the Pashtun tradition. But what people heard was not the Khan but the poet. "This boy has done me greatest wrong. But no one will harm him. He grew up in this house; this is his home, so he will stay here. He has no skills so he will still work here in my gardens."

He paused and with eyes on the boy who was looking up in disbelief, he said, "I don’t want to see you again". He walked away delivering this poetic judgment. The last bead is added to our string of stories about the poet and the knot tied.