Director Alankrita Shrivastava tells compelling stories of four ordinary women without having her characters pander to the male gaze

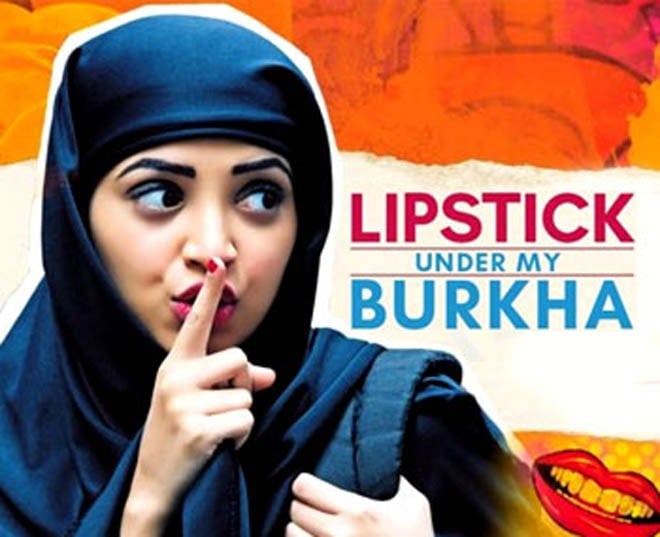

Most Indian films make it difficult, almost impossible, for ordinary women to relate to female protagonists. Under the direction of the male gaze, female characters are often one-dimensional, they are either too gentle, kind and subservient to be relatable, or too liberated for our imaginations. Rarely is there middle ground. But in Lipstick Under my Burkha, each of the four leads is docile but determined, virginal yet vampy, imperfect while illustrious, meaning that each character, much like the film, is very real.

This makes it easy for the audience to find themselves in the film. You will resonate with Rehana if you grew up, or are still growing up, under a controlling father who can’t fathom that you may have secret aspirations of your own. If your mother is emotionally blackmailing you to tie the knot with a ‘decent’ stranger for financial stability, despite witnessing you struggling to carve out a career, then you will feel for Leela. If you’re married to a man you despise, and deservedly so, then you will see yourself in Shireen. And if you’ve been taught that you’re too old or too unmarried to feel sexual desire, then Usha, or buaji as she is known, will serve as your alter-ego.

The film flits between the lives of these four women (two Muslim, two Hindu), connected by the fact that they all live in the decrepit old Hawai Manzil, loosely translated to ‘Fantasy Destination’. The film explores each protagonist’s desires, and how far she will dare to live her dreams. Out of their seemingly ordinary lives, Alankrita Shrivastava, the director, pulls out compelling and extraordinary stories. But Shrivastava doesn’t garnish these stories with platitudes, nor does she dramatise them to the point of making them appear trivial; for instance, the brutality of a marital rape scene is not conveyed the conventional way, through shock, screams and tears, but through a very humdrum, by-the-way depiction.

But while Shrivastava ensured that her female characters were not being used for the fulfillment of male sexual desire, nor as props to fill empty screen spaces or boring plotlines, she inverted this outdated model on its head and gave the men these roles. Each male character was deeply flawed and even upon searching couldn’t offer a single redeeming quality. I don’t say this in the defense of men, but simply for the sanctity of the generous realism that the film otherwise offers.

Shrivastava aptly floods the screenplay with symbolism, metaphor and allegory. While ‘Lipstick’ is singularly used as a symbol of freedom, the film is more playful with the metaphorical ‘Burkha’. Sometimes it drapes too heavy on women and cloisters them in so much darkness that they themselves lose track of their desires, and yet, at other times it provides them a shield to stalk and steal as they please.

The most interesting social commentary that the film makes on women’s clothing is that Rehana and Shireen in their black burqas, Leela in her backless, sleeveless kameez, and Usha in her matronly saaris are all equally and simultaneously oppressed and liberated. Outsiders read the women by their clothes, but the women themselves don’t necessarily feel defined by them.

The allegory that runs through the course of the film is the omnipotent story of Rosie, a potential fifth character. Narrated in Usha’s soft voice from a tattered copy of Lipshtick Walay Sapney, Rosie’s erotic tale of longing for her landlord is central to the film. It keeps us busy with its teasing words, provides material for Usha’s telephonic sex-capades, and gels the four storylines together.

Although the film has been described as vulgar, even as "orally pornographic", I found that much of its beauty was subtle. In one scene Usha/buaji has to climb an escalator in order to buy herself a swimming suit; she almost dares to take the leap of faith and plant her foot on the automatic staircase that could symbolically transport her towards sexual freedom. Just as she’s giving up, a straight line of tiny hijab-clad schoolgirls neatly climbs the escalator, all holding hands; the last little girl extends her hand to a gracious Usha. And so buaji navigates through her fears with the help of other females.

The scene is tucked away within a song, and cutting it out would not have affected the storyline at all; but the message it sends is comforting and clear: the only way forward is if we work together.

Another subtle scene that stole my heart was when a defeated Shireen walks into the kitchen to put away a plate of uneaten cake and unable to remain indifferent to her humiliation, bursts into tears, picks up the chocolate cake and shoves it down her throat. Her misery-driven consumption of chocolate was relatable and cathartic.

The fact that the Indian Central Board of Film Certification had attempted to derail the film because "the film was lady oriented, their fantasy above life," hinted that the film would make an outrageous cry for feminism. It was proclaimed far and wide as a ‘feminist movie’. Does the film show that both women and men have dreams and desires? Yes. Does it depict both women and men have the right to have said dreams and desires? Not entirely. Does it depict both women and men have access to achieve said dreams and desires? Definitely not.

What the film does do is hold a mirror to society, show us the nitty-gritty as well as overarching ways in which male and female desires are differently treated, understood and imagined. It shows us the real, brutal cost women have to pay for having dreams and chasing desires. The film doesn’t provide a neat, linear solution to defeat patriarchy, but perhaps that’s because the answer to patriarchy can’t be packaged as a magic formula, to be digested in 1 hour 50 minutes?