Web-logs became popular among niche networks and spaces of discourse in the mid-2000s, but today blogging has become effectively defunct, obsolescent, anachronistic, in other words -- dead

New formats and mediums of expression are constantly arising, changing form, being challenged and manipulated and gradually dwindling away or becoming irrelevant. However, a decade ago if one were to suggest that blogs would be more or less extinct in a span of a few years, one would have been laughed right out of the new cyberspacey self-publishing world that was blossoming back in its heyday.

Web-logs, or blogs as they came to be known, were all the rage when they started becoming popular among niche networks and spaces of discourse in the mid-2000s. No doubt, this new format and means of publication has impacted and changed many traditional forms coming under its sway, though ironically it could not outlast the forms that rehashed and appropriated it. In 2017, then, one can claim in a newspaper article that blogging has become effectively defunct, obsolescent, anachronistic, in other words -- dead.

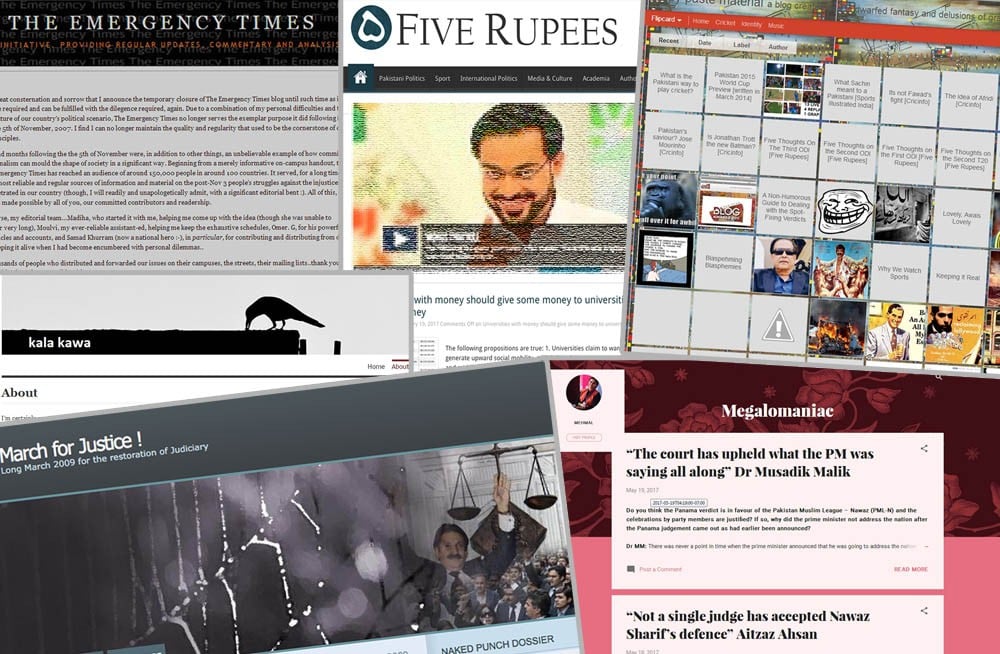

In Pakistan, the rise of blogging precipitated a new kind of ‘digital’ public sphere populated by young internet-savvy commentators. This space came to be known as the Pakistani blogosphere, and was the social media before social media was really a thing. Twitter was marginal at best, and Facebook and MySpace were used for sharing things entirely different at the time than opinionating. In contrast, blogs were a way of sharing opinions, anecdotes and accounts of a wide variety and disposition. A number of publications that were widely read and commented upon quickly populated the fringe community of internet users that was the Pakistani blogosphere.

"We started our group blog in 2006, it was me and two or three friends who had gone to high school together," says Ahsan Butt, one of the founding members of the popular blog Five Rupees. "We did it because that was the golden era of blogs and that was the thing to do." Butt and his friends used to have long email chains that would comment on current affairs, politics, sports etc. At some point they decided to go public with their witticisms in the form of a web-log and that was the birth of Five Rupees.

To date, this blog has been one of the most consistent threads in Pakistani blogging - however, this too waned after enjoying a brief revival and a brand new domain a few years ago. "I definitely think blogs are now dead as a form. Nobody has blogs anymore," says Butt, adding that even though fiverupees.com still exists as a domain it is scarcely updated owing to various commitments of its contributing members.

In 2007, the Pakistani blogosphere faced a new kind of political challenge along with an opportunity to grow in the form of the Lawyers Movement and its clampdown in the Emergency that was imposed by General (retd) Pervez Musharraf. "From March 2007 onward, there was a palpable sense of enhanced interest in the political sphere," says Ammar Rashid, one of the editors of Emergency Times. The blog was an "attempt to circumvent the mainstream media blackout and get out news and opinion about the protests," adds Rashid.

At the peak of the Emergency a "media blackout" was imposed, and in this period blogging became a veritable tool of resistance for those organising on the ground. "When the TV channels were off air, the best way to get information about what was happening or who was arrested was through blogs," notes Qalandar Bux Memon, who was active in the movement and wrote for the March for Justice blog. "Blogs were the best way to communicate from outside and inside the country and different centres of the movement."

In its heyday, even influential leaders like Asma Jahangir and Aitzaz Ahsan wrote posts on Emergency Times. After the Emergency, the editors of the blog decided to discontinue it due to personal commitments and the fact that democratic rule had been reinstated.

The post-2007 democratic era saw a mushrooming of many Pakistani blogging mainstays, political and non-political alike. "Post-2007 blogging became a lot more about politics and culture in Pakistan," says Ahmer Naqvi who used to blog under Karachi Khatmal, a pseudonym.

Another famous blogger, Kala Kawa, who prefers to stick to this pseudonym, says he started blogging in 2010. As someone invested in a Pakistan eventually transitioning towards full democracy, his "focus was mainly on those characters who were clearly "plants" to discredit democracy as a venture entirely." Hence he would focus his satirical critiques on "people like Zaid Hamid and Shahid Masood." He was ultimately battling against "an image of Musharraf’s years being "better" [which] was being rosily repainted right before our eyes."

Around the same time, we saw the rise of the new micro-blogging format known as Twitter. Bloggers initially gravitated towards Twitter as a means of increasing the audiences and circulation of their blogposts and in the start, Twitter and the WordPress/Blogspot scene worked as a synergy, but later Twitter cannibalised blogging and began to make the scene redundant.

"The onset of democracy made the blogosphere more partisan – divided between ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’ blogs," says Umair Javed, a contributor of Five Rupees. But he adds that what killed blogging was Twitter and to a lesser extent, the rise of web-friendly English language newspapers and their affiliated blogging sections. "Writing for newspapers became easier for a population historically kept out of print media," says Javed.

"I think Twitter completely destroyed blogs," concurs Butt, adding that he rarely updates his blog because whatever needs to be said is easier said in five to six tweets, or a newspaper opinion piece.

"I remember by 2009, everyone whose blogs I would follow, moved over to Twitter, which meant they wouldn’t blog as much," says Naqvi. As a micro-blogging format, Twitter provided instant feedback. Naqvi says Twitter "took away the most important part of blogging, which was the comments section - Twitter itself was a giant comments section." As people’s attention spans became more and more fragmented, the bloggers began relying on twitter-threads to dish out their unconventional opinions.

In the years that led up to the 2013 elections, Twitter too became a heavily contested space populated by several "patriotic bots" and fake accounts. These accounts began policing opinions and drew those populating the microblogging forum to the margins of social media.

With the popularisation of Twitter also came the far-reaching tentacles of the state apparatus. "The surveillance state has definitely expanded, the intelligence agencies are wiser," says Butt. "Their eyes are wider, their ears are larger." Kala Kawa says he started self-censoring his Tweets, despite having an anonymous account "around the time ISPR became more active on Twitter, indicating that ‘they’ were watching."

Mehmal Sarfaraz, a journalist and blogger recalls that "back in the early days, one could get away with saying a lot on social media. Now people are more careful due to the Cyber Crime Bill." As a result, she adds, "social media is now self-censoring like mainstream media does. The fear of being ‘picked up’ or stepping on someone’s toes is now more palpable than ever."

"The intelligence agencies today seem fixated on the idea that that the next major attack on Pakistan will take place through 5th generation warfare, insidious blogs, and ‘psy-ops’," says Javed. He says that the Cyber Crime Bill has led to a considerable amount of self-censorship as well, with overtly confrontational topics being sidelined for more vanilla politics and cultural content.

The other significant death-knell of the Pakistani blogging community was the rise of the veritable newspaper blogs. "One of the things that happened, is that the people who were doing it for no money and simply for the labour of love," says Butt, "the ones who were good at it, got taken over by established media institutions who saw an opportunity or a threat." English dailies like Dawn and The Express Tribune, to stay with the hip and trendy times, launched their own blogs.

"I started blogging for Dawn around 2010," says Naqvi, "The Express Tribune started this heavy clickbait-y usage of blogs; I think that put off a lot of bloggers, it also changed the nature of the game."

The old bloggers who managed to become influential have now shifted to the older, more conservative medium of newspaper columns. Naqvi, himself got the opportunity to write for local newspapers as well as CricInfo.com through his earlier blogging activity.

Sarfaraz tied her blogging with professional journalistic aspirations from the get-go. "I got into blogging just a few months before I joined journalism so most posts on my blog are actually reports, interviews, columns and editorials that I wrote for newspapers."

Ultimately blogging managed to change newspapers themselves as they adapted, or at least blog sensibilities became incorporated into online newsprint. "There was a big shuffle in the roster" notes Naqvi referring to newspapers. "The way they began writing was a result of how bloggers wrote about things."

Sarfaraz suggests that "the blogging scene actually penetrated the mainstream media and made them think out of the box." They forced newspapers to make their websites more interactive. Ultimately, however, blogs themselves didn’t survive the dual-onslaught of the leaner Twitter post and the denser newspaper blog that grew out of the original format.

Blogging, as it was originally conceived is now a thing of the past, being replaced by Twitter-threads and long Facebook posts which are, as Kala Kawa notes, only meant for one’s immediate audience that is contained and markedly different from what originally a blogpost would reach.

The term ‘bloggers’ now widely refers to influencers and opinion makers on the social-web who command large Facebook pages and Twitter followings. Recently the ‘bloggers’ who went missing were not bloggers in the traditional sense, but administrators of influential Facebook pages with political content, which have since then disappeared off the face of the social web. On the pages that did survive this onslaught, politics has now been replaced by new kinds of branding and e-commerce sensibilities ala Buzzfeed-clones, like Mangobaaz, that no longer ascribe to the unruliness that the blogosphere once espoused.

Bloggers are no longer the new kids on the block - they have moved onto bigger things in life and their blogs have become stagnant forms lacking updates and vivacity. The Pakistani blog generation has grown up over the past decade. Kids who had ample time to compose whimsical posts with pictures and links for no monetary retribution, have now gotten jobs, spouses and responsibilities.

"People in circles we were in, grew up," says Butt who now holds the position of Assistant Professor at George Mason University in the US. "Maybe they got married and had kids. The idea of perfecting this 500-word post is a bit too much especially if you’re not getting paid."

Ultimately, of the famous bloggers, the ones who could get paid to write posts made a profession out of it, the others used their blogging career as a stepping-stone onto other more lucrative opportunities in the development sector and other industries. As the Pakistani bloggers grew out of blogging, Naqvi notes that a new crop of bloggers didn’t come to replace the original innovators -- hence we witness the end of an era of an internet self-publishing community.

Possibly in the most rapid fashion, the future has become history. What was the cutting-edge and avant-garde form of futuristic expression is now at best an anachronism or a digital archive. The blogs that were once breaking new ground still exist on the web as crystallised forms of expression -- most haven’t been updated in a few years, some have posts declaring the cessation of updates due to one or another reason.

Far from their once future-bound essence, these blogs that once populated Pakistani cyberspace and heralded critical discourse of a new generation now lie stagnant as mementos and memorabilia of a past world. In 2017, they read less like a current medium, and more like pamphlets and zines baring witness to a historical era. Whether they will be one day displayed in museums or archival catalogues, or whether they will rot on the margins of the internet, is a question left to the future to come; for now, these forums and formats of expression deserve to be memorialised -- in a traditional newspaper article -- as a form of the new that became old too fast.