Purposeful sameness turns Sajjad Nawaz’s drawings of landscapes into a timepiece on display at Canvas Gallery

Cholistan or Rohi in the local patois, (deep in the south of Bahawalpur) as it appears in Sajjad Nawaz’s drawings grouped together in an ongoing show ‘Land Escapes’ at Canvas Gallery, Karachi, from July 18 is inescapable. Draped in cloud, drenched in sun, swept clean by inexhaustible tides, the desertland is always there, dutifully magnificent, stoically radiant. It fills the postcard, frames the visit, defines the experience. It captures the imagination of all who pass by.

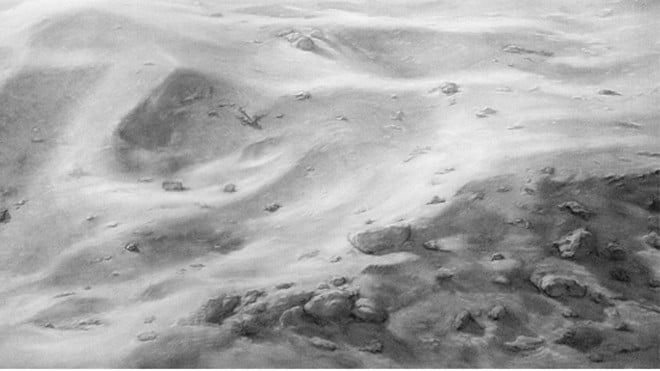

But, in and around the sandy wasteland there is a great deal that does not readily come into focus. Beyond its magical realism lies the geographic magic done by the hand of nature and humankind. The hidden geography of Rohi can be seen in the rocky points and mouldering dunes cloaked in grey sand, in stipples of green and brown along the ridge, in dots of mica and mineral stone tucked into the ochre belt. But it must also be called up from hidden places of collective memory, these clouds of history.

A roomful of Sajjad Nawaz’s drawings is uncanny first of all because so much -- beneath the flamboyant variety -- is much the same and repeated. There is the same, always unsettling relation between sea, land and sky: the sky ostentatiously dominant, the ground plane of sand and soil, somehow contriving to hold their own. There is the same fixity and clarity, with only very occasionally the action of clouds way up in the top of the frame seemingly beginning to blur things a little. The same landscape without foreground, the same view from nowhere and the same perfect yet enigmatic balance but all of it unstressed, clean and informative with the feel of efficiency. Maybe proposing some other measure of visibility than the human, but doing so pragmatically; trying to do its best by the scenery; repeating itself, but not according to any algorithm or set plan. All that is necessary to Nawaz’s purpose is that there be enough sameness in the sequence for the images to declare themselves a timepiece.

A landscape, (borrowing a phrase from Roland Barthes about the camera) is a clock for seeing. But ‘seeing’ is generally very unlike what happens on Nawaz’s plane. Seeing is unstoppable, momentary, continuous, forgotten as it happens, embodied, inattentive, arbitrary and appetitive. ‘Momentary’ may be the key word in the list here - precisely because it means something different from ‘arrested’ or ‘instantaneous’. Momentary means flickering in an ongoing flow. And Nawaz’s images do not flicker. They do not exist between a before and after, experienced as pressing in on them and interfering with their Now. They are unblinking. That’s why the words on the back of Constable’s cloud studies truly usher in a new epoch and point far into the future. "In such an age as this, painting should be understood, not looked on with blind wonder, nor considered only as a poetic aspiration, but as a pursuit, legitimate, scientific, and mechanical," writes Constable.

Ostentatious is a crude word for the many different ways the sky fills the frame in Sajjad Nawaz’s large-scale drawings on paper in charcoal and graphite. Most of the time, everything that appears on surface is perspicuous and dramatic, the sky no more so than the solids and liquids. But the sky is dominant, quantitatively and qualitatively. It is meant to register as larger, higher than we ever naturally take it to be - dictating the note to the world far below.

Part of the point of Nawaz’s handling is to maximise detail and demarcation, where land, sky and water meet - not to have everything be swallowed by atmospherics but to let the flattening of the flatlands be savoured for what it is, a thing with its own kind of suggestiveness and difficulty. The fact that the ‘scenes’ as a whole are so little contained and supported at the sides - wingless, as an art historian called this compositional type - chimes in with this sense of flattened, elusive immensity.

The sky, by comparison, is massive, well articulated, moving backward in layers and stages that are much easier to grasp - may be cumulative would be the word for the overall feel and organisation. It does not seem at all stressed or paradoxical that the sky is given more space in the drawing than the land. The eye tends to compensate for the disparity.

"What should we have thought," asks John Ruskin in Modern Painters, "if we had lived in a country where there were no clouds, but only low mist or fog - of any stranger who had told us that, in his country, these mists rose into the air…I am aware of no sufficient explanation of their strange mingling of opacity with a power of absorbing light. All clouds are so opaque that, however delicate they may be, you never see one through another. Six feet depth of them, at a little distance, will wholly veil the darkest mountain edge; so that, whether for light, or shade, they tell upon the sky as body colour on canvas."

It seems to be the mixture of opacity and absorptiveness that fascinates Nawaz. He is interested in the analogy between the behaviour of clouds and the characteristics of their medium - body colour for the painter, filmy emulsion (blending opacities into transparencies) for the photographer, who is in continuous dialogue, real and imaginary, with the technician pulling the print eventually from its chemical bath. Nawaz is preoccupied - to the point of obsession - with the actual, physical surface of his end product and the distance it takes from the objects it attends to. Surface interacts with format. The quiet preponderance of the sky gets more interesting the more one appreciates the intricacy - the deliberateness - of what is done to the land.

Having lived in Cholistan, searching for and rediscovering it, Sajjad Nawaz claims it as a new land. The work consists in the process of staking the claim, and its meaning lies in the attention it draws to the imaginative power of place. A new land, especially one discovered in the context of an issue as emotive as global warming, is a potent symbol. In some of the drawings, the sea recapitulates the sky, as if hardening and epitomizing it. The world is in order. Nowhere is a good piece of real estate. Nature from nowhere looks better than usual.

The circuit of questions set off by these the monochromatic drawings is typical of those provoked by the pictures in general. These landscapes exist in the space between truth and verisimilitude. The truth of the ‘landscape’ is that it is a cliché, and the reality is that the cliché is beautiful. Drawing is the right medium to expose that non-contradiction because it is not afraid of repeating itself.