Do advertisements reinforce a reality or create one?

Eight in the evening was the height of activity in every household. As the Pakistani male egos of fathers explained the importance of news channels and the sport-oriented brothers pleaded to get a glimpse of the cricket match, the sisters and mothers proudly guarded the television control to view their nightly episode of the current series.

Let’s skip to contemporary times, with all members of the family in their separate rooms indulging in media through a range of sources. Everyone isn’t in the same place -- which makes it harder for the advertising agencies to get attention.

This gives them a reason to expand uncontrollably in all directions. Fathers now get irritated by forceful advertisements on news websites, brothers encounter a range of ads on their social media, sisters have to wait 30 seconds to watch a commercial on YouTube before their actual video starts, and mothers receive text messages of sales happening in their favourite store. Advertisements are all around us occupying every wall, every billboard and every device.

The role of advertisements is simple; they convince consumers to purchase certain promoted products in order to maximise their profits. As Azra Noor, a 50-year-old housewife says, "It’s a commercial age, there is more focus on quantity these days compared to quality".

Advertisements thrive in a consumerist society, prompting the population to keep on spending a few more rupees. Everyone thinks little of these advertisements, treating them as an amusing routine or nuisance. Unbeknownst to the people, such commercials do create shifts in the consumer’s minds -- increasing sales.

Advertisements have an unconscious psychological effect on the average human. As human beings we use sensory perception as one of our primary means of obtaining information and gaining first impressions of things. In the corporate headquarters of NeuroFocus located in Berkeley California, an experiment was done in 2011 where electroencephalogram (EEG) was strapped to the head of subjects of a study and it picked up brainwaves created by the electrical activity that passed between neurons when the brain processed anything. As a commercial was played, the subconscious effects of advertisements were seen as tall peaks in parts of the brain. Such peaks are usually invoked by emotion, attention, and memory.

If an advertisement is repetitive, catchy, and sentimental enough, the brain incorporates the ideas shown in the commercial, and is prompted to buy the product. These scientists tell advertisers how to make better commercials in the light of their studies.

Wafa Zainab, an 18-year-old Youtuber, explains, "My business sir, showed us a Molty Foam ad where the company put up 150 billboards made of mattresses in many parts of Pakistan. These mattresses could be flipped at night and turned into beds for homeless people. The company was creative and raised social awareness, while attracting more customers. This had a huge impact on me and made me want to help people more."

In a PBS documentary titled Merchants of Cool, American advertising agencies try their best to find out what’s popular among teens in order to sell what they desire. But at a point, they go so far ahead to even ‘manufacture those desires in a bid to secure this lucrative market’. The line between advertisements reinforcing reality and advertisements creating a reality has become blurred. No one can determine if the latter borrows from the former or vice versa.

In a 1985 life insurance advertisement a little girl sang, "Aye khuda meray abbu salamat rahain" (Oh God, may my father stay healthy), wishing for the health of the breadwinner of the family. Interestingly, a similar life insurance advertisement can be seen in present day. The Jubilee Insurance company came out with a commercial starring Nouman Ijaz that shows a father worrying about his life because he had to pay for his son’s education, his daughter’s marriage and his wife’s old age. This advertisement again emphasised on the importance of the breadwinner of the family. Ali Akbar, a young Islamabad resident, gave his opinion that most of the Pakistani commercial storylines are the same. Are the commercials the same because the economic structure has remained unchanged? If the female is the breadwinner, would Pakistani commercials be more progressive or different?

According to the Labour Force Surveys done by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics in 2001-2002, 9.86 per cent of the female labour force was active compared to 48.04 per cent of the male labour force. The same survey was done in 2014-15 and a change was noticed. While the male participation rate only increased till 48.08 per cent, the female participation rate rose to 15.81 pc.

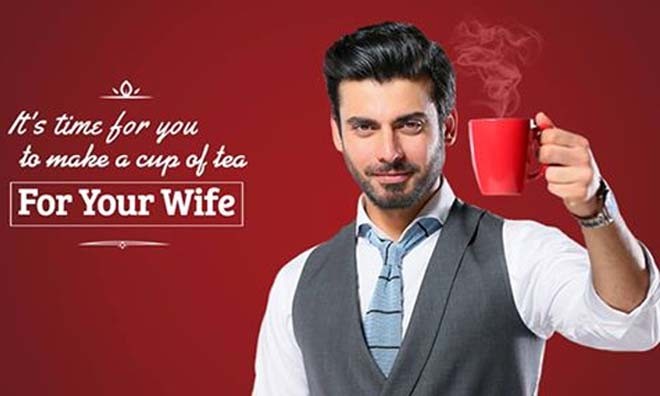

This tiny progress can be seen in rare advertisements because most companies are afraid of the risk such commercials entail. Most tea advertisements show a female pushing a tea trolley and serving tea to her family/in-laws, but a recent Tapal Danedar advertisement with Fawad Khan, a male making tea for his female counterpart, Momal Sheikh, caused a pleasant stir in society.

Despite the positive message, the female was seen returning home with grocery bags in hand, continuing the same trend. Advertisements like these are still more invigorating compared to the advocacies of fairness cream and the stereotypical marriage injected commercials.

Considering the blurred line between reality and advertisements, could commercials correspond to changes in the economic structure of society? Can they at least reinforce a new and emerging perspective in Pakistani society?

For now, our sluggish advertising agencies are practically at a standstill but is there hope for a more propitious future?