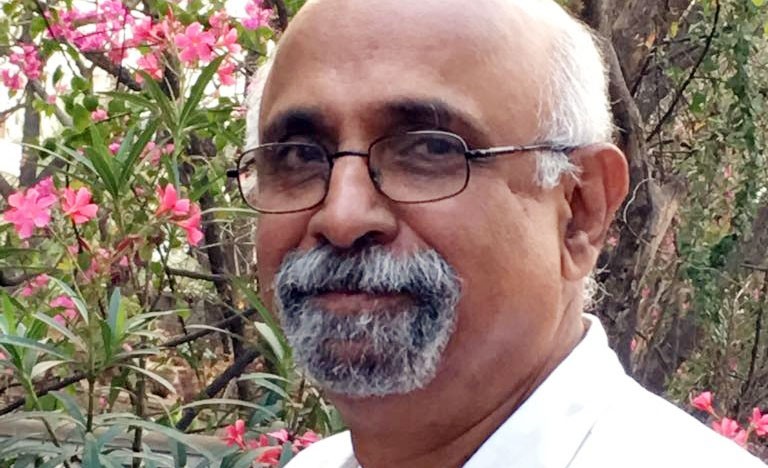

C. Rammanohar Reddy is a writer and commentator based in Hyderabad (India). He was Editor of Economic and Political Weekly, Mumbai between 2004 and 2016. He is also the author of the recently published 'Demonetisation and Black Money' (Orient BlackSwan, 2017). Here he replies to various questions about the growing intolerance in India in an email interview with TNS.

The News on Sunday: Why this sudden anger against cow slaughter? Are these incidents spontaneous or product of a conscious and sustained campaign against Muslims by Hindu nationalists?

C. Rammanohar Reddy: Cow slaughter is not a new issue in India. It has been around for decades. For instance, in 1966 more than a hundred thousand people who were demanding a ban on cow slaughter marched on Parliament in New Delhi. They were stopped only by police firing in which scores were injured and some died.

However, over the decades, the issue has been under the surface partly because the right-wing Hindu groups were not strong enough to put pressure on the government, partly because there was no wider public demand for a prohibition on cow slaughter and partly because the government recognised the value of dairy farming in supplementing farmers’ incomes.

Things started changing from the 1990s when first some Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led state governments imposed a ban on cow slaughter. Then in 2014, the BJP successfully made what it derisively called the "pink revolution" (referring to the flow of blood in slaughter houses) an issue in the general elections. India had by then emerged as one of the biggest (buffalo) beef exporters in the world and this was falsely made out as violating Hindu sentiments about the cow.

But the message that Hindu feelings were being outraged under the previous Congress government was successfully put across and paid off electorally for the BJP. The major exporting firms are owned by Muslims and most of the workers in this activity are Muslims and Dalits.

The stoking of this issue has now turned into a fire after a near country-wide ban on cow slaughter. The BJP governments in states where it is in power have actively encouraged the formation of vigilante groups, the gau rakshaks (cow protectors), to help enforce this ban. It is these groups who have been behind the current violence against Muslims and also Dalits for allegedly (wrongly in almost all cases) carrying out cow slaughter. These rakshaks are mainly young men without jobs. It serves the ruling party well to divert the attention of these unemployed men to protection of the cow.

TNS: What is happening in the Indian society at the moment? How did religion creep into the multicultural secular India? Who are these angry mobs? Why are they so angry and what has changed to embolden them so much?

CRR: Religion has always been part of Indian society; it is religion in politics that is now ascendant. It would seem that in spite of efforts to make secularism strike deep roots in India after 1947, the roots have not been strong enough to withstand passions as at present.

Extremist Hindu groups have been working since the 1920s, they became mainstream in the 1970s and 1980s, and started acquiring state power from the 1990s. The rise of the Hindu right is beginning to take the form of Islamophobia in some parts of the country.

What we are seeing now is a kind of "Zia-isation" of India much like what happened with Islamisation of Pakistan in the 1980s. The difference is that while in Pakistan, Islamisation was directed from above, in India mobilisation of Hindu extremism started from the ground upwards.

The emergence of the gau rakshaks is taking place in a larger context of mobilisation of Hindu anger which shows itself in violence against Muslims and even other minorities like the Dalits.

The refusal of the State to act to prevent this violence says something as well. In 2016 and again more recently, the Prime Minister made statements criticising the vigilante groups. But these statements were made a long time after the bouts of violence. They were also one-off and mild statements. So the gau rakshaks remain emboldened.

TNS: How correct is it to see this rise of the right or BJP as a consequence of the failure of the Congress. Did the language of ‘pluralism’, ‘tolerance’, freedom of expression die a natural death with the fall of Congress?

CRR: The rise of the angry Hindu right is not a sudden phenomenon. It became stronger by the year from the mid-1980s. It was not that the Congress itself always stood strongly for pluralism and against communalism. At times, the Congress Party was a cynical and passive witness to the rise of communalism. So the rise of Hindu extremism today is the result of twin processes -- the successful mobilisation by the BJP, RSS and their affiliates and the corresponding failure and unwillingness of the Congress Party and others to counter them.

The more important question is if this retreat from tolerance and the State’s passive if not active support for discrimination against the minorities is something permanent or only temporary. From the ferocity of the push-back against tolerance and plurality, one should be worried. But one remains hopeful that a society with a long history of openness to all faiths cannot be changed so easily.

Read also: No map for deep currents

TNS: Is ‘cow protection’ a strategic choice for BJP or they do it out of conviction? It is being said they are doing it to deflect attention from some real issues like economy, Kashmir, farmers’ suicides. Comment.

CRR: One must understand that the cow has an important place in the Hindu ethos. To that extent, there is a conviction and not opportunism about the Hindu political parties and organisations demanding and succeeding in putting in place a ban on cow slaughter.

However, until now there was also tolerance and respect for diversity in food habits. While Hindus in most parts of the country revered the cow and did not eat beef, there was acceptance and even respect for the food habits of minorities like the Dalits, Muslims, Christians and people living in North-East India for whom beef was an important part of the diet.

That has changed now. Indeed, a worrying trend is that in the aim to "Hinduise" Indian society, there is a larger push towards vegetarianism as well. The crackdown on abattoirs in Uttar Pradesh (where goat meat was processed) and even the recent decision by Air India to stop serving meat on domestic flights should be seen as part of this drive. But only a very small section of Indian society -- the upper caste Hindus -- are vegetarians.

Yes, as I said earlier, mobilising the gau rakshaks and making cow protection an inflammatory issue serves to divert attention from serious problems like unemployment and helps to contain economic resentment.

TNS: How do you look at the role of media -- electronic, print and social -- in this situation?

CRR: The media in general has failed in its job. There are a few exceptions but on the whole both the English and Indian language media in print and TV has not been able to stand up for secularism and plurality and against communalism. Indeed, in many respects it has been an active supporter of the mobilisation of communalism. It has also given expression to an aggressive form of what can only be called "Indian-Hindu" nationalism. This is especially so on television.

Social media often sees a hate-filled spouting of views and the propagation of fake news meant to strengthen Hindu extremism. A few groups try to fight back; a few media outlets try to speak truth to power. But there are not many.

TNS: How is this impacting Pakistan India relations? How does an ordinary Indian view Pakistan and Pakistanis?

CRR: As you know India-Pakistan relations have taken a dive since 2015. We are now a long way from the bonhomie of 2004-05.

On the ground, the media, on encouragement from the ruling establishment, is stoking the embers of an aggressive form of Indian-Hindu nationalism that is directed mainly at Pakistan. This nationalism also takes the form of Islamophobia, which is now a global phenomenon. Then there are the unrestrained and extreme views expressed on social media mainly by the middle and upper classes.

All this naturally affects the feeling of people towards Pakistan.

At the same time, I would not be pessimistic about the future. There are often surprising events that tell you the opposite about what ordinary Indians feel about Pakistan. For instance, as recently as in 2015, the biggest grossing Hindi film (and currently the third biggest grosser ever) was Bajrangi Bhaijaan, a straightforward story about a simpleton Hindu who risks his life to take back to Pakistan a little girl who gets accidentally left behind in India. It was a universal story about a lost girl. But it was also a particular story about a man proud of his Hinduism and Indianness caring for a Pakistani Muslim.

Such films do strike a chord and perhaps tell us that there is room for optimism about the feelings of common people in both countries towards each other.

A shorter version of this interview was published in The News on Sunday, July 16, 2017