How India views Pakistan, and how it views its own Muslim population have always been two sides of the same coin; in BJP-ruled India, this has become all too apparent

A strange thing has happened in recent years: the word peace, "shanthi/shantha" in Sanskrit and all Sanskritic Indian languages, a common Indian name for women and men, and a word that is part of everyday prayers in Hindu households -- "Om Shanthi, Shanthi, Shanthi-hi" -- has become a pejorative. It is used as a word of abuse, or accusation.

An Indian who wants her country to seek peace with itself, and with neighbours, particularly with Pakistan, is someone who is backward, a moron, an offspring of an illegitimate relationship, betrayer of India, and Indianness. At the very least, any talk of peace with Pakistan is likely to be met with a raised eyebrow and a "You’re one of those, are you?"

In truth, we did not get here yesterday, or even in 2014. What we see today is the product of over 70 years of bad history that began over partition, and got handed down from generation to generation. The hope that memories would fade, that a new generation of Indians and Pakistanis, would step up to normalise relations, was misplaced. Instead, each generation has experienced war or terrorism or failed talks.

Still, the present public animosity in India towards Pakistan is at a scale that has never been so evident earlier, at least not in recent memory. One reason, of course, is that social media has enabled the easy public expression of views in a way that was not possible before.

As well, Indians who have come of age in the last 10 years have no significant memory markers of India-Pakistan ties aside from the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai that can offer a counterpoint to the narrative of terrorism from Pakistan. Instead, since Modi’s ascent to power, there has been a Pathankot, most certainly in response to Narendra Modi’s Lahore visit, an Uri, surgical strikes and the rest.

Rewind to 2001-02. After the big chill following the attack on the Indian Parliament and eyeballing at the border gave way to a thaw, it seemed as if a repressed bonhomie between the citizens of the two countries had erupted. Cricket, music, food, culture, visits, shopping, Bollywood -- they all brought India and Pakistan together in one big cathartic outpouring.

26/11 put all that in a box and shelved it. Pathankot has become the untearable duct tape on that box. Even the formidably popular Fawad Khan did not survive the anti-Pakistan sentiment that has held sway since then.

There was a BJP government at the time of the parliament attack and the Kargil war. They were both seen as a betrayal of Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee’s outreach to Pakistan, to the same Sharif, at the same Lahore. But what is different now is triumphal Hindutva, riding high on all the BJP’s electoral victories, which has fused religion, militarism, and patriotism to create an aggressive nationalism.

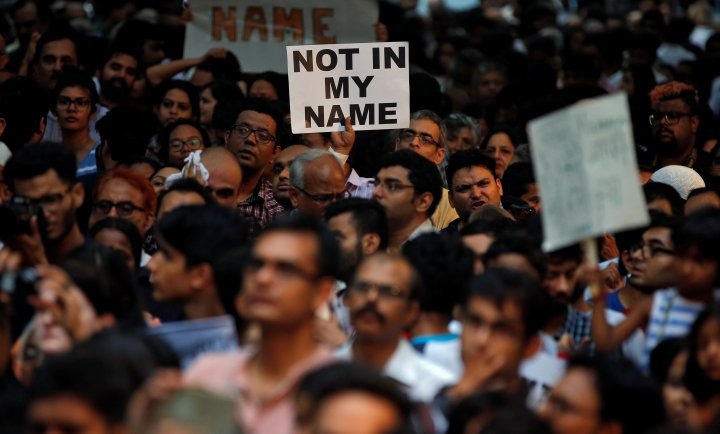

The nostalgia-driven people-to-people push that gave popular legitimacy to the 2003 ceasefire and the dialogue that began in 2004 is no longer possible. In the new mood, citizen and civil society appetite for contact with Pakistan has all but vanished, except in the few determined quarters that are not cowed down by the vitriol spewed on them.

Read also: A post-truth age

It is this same mood that determines there will be no more accommodation in Kashmir and valorises a soldier who uses a Kashmiri as a human shield, that changes military terminology of a secular army from ‘killed in action’ to the religious ‘martyred’.

The sarkari refrain is, "There is nothing to talk to Kashmiris about," along with, "There is nothing to discuss with Pakistan on Kashmir except terrorism and the return of PoK." Most of the media parrots this faithfully, and the message hits the target.

The jury is still out on the military outcomes of the "surgical strikes" after the Uri attack, but they were a political signal reiterating to a new and demanding Indian public that Modi had not turned into a "libtard". They also set a new bar for government responses to Pakistan -- the government can lower this only at great political risk.

There is no logic to the argument that "they are killing our jawans in Kashmir, therefore the government must give a befitting response," because what that means is that more soldiers should die. Modi, with all his popularity, should be able to expose the senselessness of this. In fact, if there is one leader in the country today who could come up with the most imaginative solutions to Kashmir and ties with Pakistan, and sell it to the Indian public, it is Modi. After all, he convinced India to live without money for three or four months.

But BJP needs more Hindutva to win more elections. As the lynchings of Mohammed Akhlaq, Pehlu Khan, and Junaid and others show, Hindutva is fast redefining the Hindu-Muslim dynamic in India. In the electoral calculus, the BJP knows it does not need Muslims to win elections. How India views Pakistan, and how it views its own Muslim population have always been two sides of the same coin; in BJP-ruled India, this has become all too apparent.

But what about Pakistan? I was one of those who cheered Modi’s 2015 Lahore touchdown as a "breakthrough moment" in India-Pakistan relations. Pathankot was an immense let down. Why do even liberal Pakistani political elites, including its powerful media, justify terrorism in India? Why have they not pushed for the punishment of the Mumbai perpetrators?

In this dark cloud, an Amarnath yatri last week told me there could be a silver lining somewhere, still hidden. He was in a convoy of yatris travelling under heavy security escort from Jammu to Kashmir for the pilgrimage: "War is not an option," said the man from Madhya Pradesh. "If we have 110 nuclear bombs, they have 130. "Aamney saamney baith key hal karo, larai sey kya hoga?" There must be more people like him in India, and in Pakistan, but at the moment, they are not loud, and we are not hearing their voices enough.