A collection of articles about the laudatory journalism and politics which was being practised during the stifling dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq

There have been a handful of journalists in the 70-year history of print journalism in Pakistan who had preserved the sanctity of their pen and profession by penning down truth even during the dark days of martial laws. And Prof Waris Mir tops the list of those gutsy intellectuals.

A leading Urdu writer and analyst of his times and the chairman of the Journalism Department at Punjab University Lahore, Prof Waris Mir died of a sudden heart attack at the young age of 48 on July 9, 1987. He belonged to that era of Pakistan’s history when speaking one’s mind was a punishable offence.

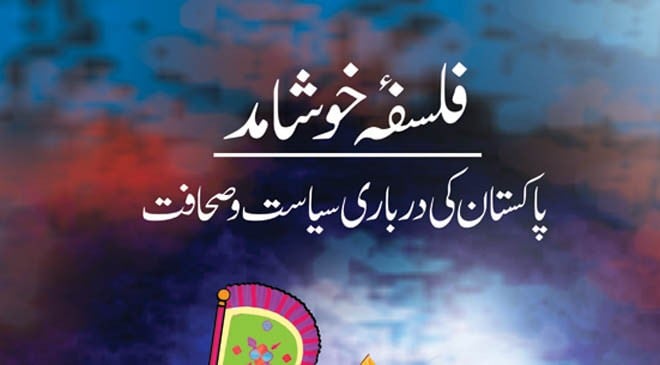

On the eve of his thirtieth death anniversary on July 9, the Waris Mir Foundation has published a new compilation of his writings: Falsafa-e-Khushamad; The Philosophy of Flattery. Basically a collection of his articles written in the 1980s, the book is all about the laudatory journalism and politics which was being practised during the stifling dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq. The subtitle of the book, The laudatory Politics and Journalism of Pakistan makes it all the more comprehensive as to which open wound of the ailing body of journalism and politics is being probed at in this 370 paged book.

Those who know Waris Mir would already identify that the man during his intellectual battle with the forces of extremism, kept the ball(pen) rolling with arguments, research and factual retorts while penning down his columns that were published in Daily Jang and Daily Nawa-e-Waqt. The book, in its entirety addresses those laudatory journalists, writers and politicians who made a deal by signing off their intellectual conscience to a dictatorial regime for the sake of expediency. At the same time, Mir also celebrates and compliments those writers and intellectuals who stood with truth, objectivity and sincerity to the masses even when offered riches or something similar.

Prof Waris Mir himself belonged to the later class of intellectuals. The synopsis of the book, a detailed study into the minute nuances Mir made in his writings, is a brief introduction to the complete thesis of the book itself. Written by Amir Mir, it mentions one column where Waris Mir questions his readers, "Take a look at the 36-year old history of Pakistan and ask yourself, who has been the real ruler of the country? Feudalism? Business owners? Bureaucracy? Or the Army? The truth is, whatever the mode of rule has been in this country, the real force behind any mode has been the political economy of capitalism.

This dependence on domestic or foreign money to rule over any country, especially for those rulers who come into power only with the help of a few cronies (and not the popular vote) arrive at a point where flattery or laudatory praise becomes essential for them. In the beginning, one likes to praise themselves and then once this weakness for being lauded is recognised by those who are ready to barter a deal with their conscience, this self-praise is taken to the next level where false pride falls prey to flatterers and a ruler hears (reads) only what he likes to hear since he surrounds himself with such oily tongued people who sing the songs of praise alone, completely avoiding any constructive criticism or progressive thought for improvisation." (Khushamad, dil ka muhlak tareen marz; Nawa-e-Waqt, 1984).

The Zia regime used to treat progressive minds, scholastic writers and philosophic thinkers as blasphemers. Speaking out, that too at the behest of the people of Pakistan, with a mission in mind -- ‘to write for the posterity, to speak as the people’s voice’ -- was a task not many could take up in those oppressive days.

Waris Mir was a strong proponent of freedom of thought and expression. Of course, a scholar who would think of tomorrow and how the future of an entire nation should be planned, would need breathing space to express his ideas. That breathing space was not something a conservative military dictator could allow. Yet, Waris Mir was not one of those people who would ask permission to think, express and write. He wrote his heart out. His words would become even more pinching, even more stinging when the dictator of the time would try to freak him out or put a price on his commitment.

"Freedom of press means being able to have your say and freedom of thought means having the liberty of thinking originally and individually," he wrote in one of his columns while negating the frustratingly remote regulations of Zia’s autocratic rule and encouraging his readers to think on their own instead of relying on the pseudo clerics.

Waris Mir was discouraged in many heinous ways from speaking his mind. But he kept encouraging the masses to think progressively. His only source of expression was the print media - "When the media would honestly and truthfully give its people the access to real information and not disinformation, the society would itself reflect values of honesty and reliability. If the media is given freedom of expression then the political system of a country would always be held accountable and thus just like volcanic lava, the impurities of the political system could be excreted out bit by bit. That sounds easier and manageable when compared to a huge explosion that could destroy the people, the system and the country."

Like the previous books published based on Waris Mir’s writings (Fauj aur syasat, Kya aurat aadhi hai? Hurriyat e Fikr ke mujahid etc), the reader of this book shall also acknowledge Mir’s writings are not based on his opinions. Even in saying so, his opinions on paper are not based on whims or half-baked observations. When he writes a piece, he does justice to the reader by quoting references, debating with his opponents with historical, religious, philosophical arguments.

In his last column, which was published uncensored, posthumous and in its rawest form, Waris Mir directly addresses Zia who, earlier in the evening, had spoken indirectly to Mir in a meeting, calling progressive thought ‘mould and fungi’. The reason was Mir’s relentless criticism of Zia’s masochistic, dictatorial policies which never involved public sentiment. He wrote, "Those people who are no more than fungi to the totalitarian regime are actually those patriotic citizens who want Pakistan to emerge as a modern state on the globe; those who want Pakistan to have a progressive personality; those who want to encourage the masses to be intellectually equipped enough to demand for their rights against poverty, mullahism and illiteracy".

Such truth had to be said but no one else said it. Prof Waris Mir, died of unusual circumstances, but it is safe to say anyway, he laid down his life for a cause he believed in -- the fight for truth, justice and objectivity; the pursuit of national development as opposed to laudatory journalism and politics.