How practising psychiatry in Pakistan is different from the west

"But I don’t want to go among mad people," Alice remarked.

"Oh, you can’t help that," said the Cat: "we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad."

"How do you know I’m mad?" said Alice.

"You must be," said the Cat, "or you wouldn’t have come here."

―Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

The first time someone suggested it I was horrified. It was probably my first year back from America. I had gone there as a young doctor in training and my entire professional career until then, around sixteen years, had been spent in America. I got training as a psychiatrist, then went on to work at a large mental health centre in the southern United States catering mostly to people with ‘severe mental illness’. Most of these people had been ill for many years, some for more than twenty or thirty years and most had severe, lifelong illnesses such as schizophrenia, severe bipolar disorder or the like. Most of them were not able to work because of their illnesses and received small government pensions. Many of them had no family or social support of any kind and lived in housing provided by the government and managed by us.

The situation I was now facing in Lahore as I struggled to learn the ins and outs of practising psychiatry in Lahore was quite common in Arkansas where I had worked. We frequently had patients in the throes of acute illness who refused to admit that they were ill. They would be brought in to our hospital by the police or occasionally by family and friends because they were hallucinating, talking out of their heads, had not slept for days, had made a scene somewhere and were agitated and violent.

In all cases, they refused to accept that there was anything wrong and flatly refused treatment. The protocol for dealing with such patients was fairly straightforward: if the examining doctor felt that they were ill and (importantly) that they posed a danger to themselves or society, the law allowed us to detain the patient against their will for up to 72 hours after which we could make an application to the local court and ask for a ‘petition’ to detain the patient longer (up to 7 days, then again up to 45 or 180 days).

The patient was allowed (in fact required) to appear in court and could speak to the judge on their own behalf. If the judge determined that they were safe to be released, they were let go right there and our responsibility ended. In most cases, as you might imagine, one look at them and the judge granted our petition to hold them against their will and, if necessary, treat them.

Now, here I was in Lahore and all that was a hazy memory. A family had come in to see me and described a daughter in the throes of what sounded like an acute episode of mental illness. The patient herself had refused to come in but the family’s description sounded fairly accurate. It was obvious she needed treatment but she had refused to even see a psychiatrist, let alone take medication.

This was the first time I had faced such a situation in Pakistan and my US training appeared less than adequate. In desperation, I called one of my students, a trainee psychiatrist in the large public medical university where I was teaching. He appeared completely unfazed: "No problem sir. Just ask the family to give her the medicine mixed in her food or drink, we do it all the time!"

I was taken aback. Not only would this be completely unethical in the United States, it could well lead to legal charges of ‘assault and battery’ and an arrest (for me). Medicating someone against their will would be considered totally unacceptable, a gross violation of their ‘civil rights’. In the absence of a legal framework to deal with the dilemma I was facing, it appeared to be the only solution.

I later learnt that even though, on paper, Pakistan had a ‘Mental Health Act’ which was passed as far back as in 2001, it was never implemented in letter and spirit. When I later read the Act, it did indeed specify the legal steps that were to be taken in such a case. They were similar to what would be done in Western countries (the Act had been adapted from the equivalent Mental Health legislation in the UK). However, the legal (and practical) framework for the implementation of the act was totally missing in Pakistan. We could not contact the police to pick up the patient, we had no designated courts to take the patient to and there were no forensic psychiatric units where the person could be confined while they received treatment.

With some reluctance, I advised the family to start medicating the patient without telling her, to report back to me on weekly basis and to bring her in to see me as soon as she was agreeable. To my surprise, a week later the family reported that she was better and within a month she had agreed to come and see me. Eventually, she agreed to start taking medicines on her own and recovered completely (we never did tell her that we had given her medicines without her knowledge).

Since then, I have treated dozens of patients this way. Every week, one or two families come to see me with this same dilemma. I am now more comfortable prescribing medicines to such patients and in most cases, the outcomes are pretty good. Most people eventually recover and do okay. In one or two instances, families over medicated patients and ended up in the emergency room after which I insisted that the person be hospitalised and treated there.

But many nagging doubts remain. How much of a person’s illness is due to family conflict and social pressures, none of which is resolved by just medicating the patient. How would any of us feel if we found out that our spouse, mother, father or child was secretly medicating us without our knowledge?

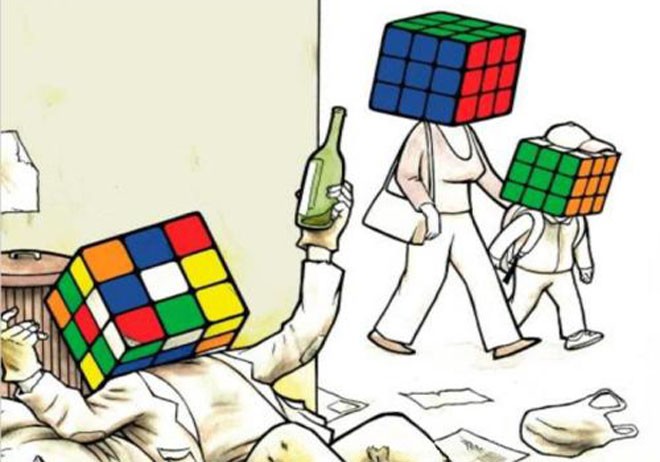

And who gets to decide our sanity anyway? Who decides that I am mad? My psychiatrist, my wife or husband, society or me?

(To be continued)