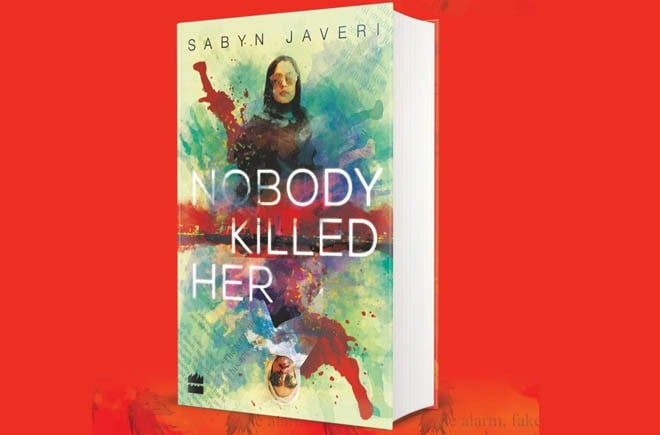

On why this political thriller is a perfect summer read for every book lover out there

Reading Nobody Killed Her is like watching a train heading for a crash. The train lurches and screeches, the sound so deafening, you feel your eardrums thumping in protest, the train carriages going off track. They knock everything down in their wake, the ground rumbling, terrified of being destroyed. You can hear the screams, the train’s siren, and the wheels squealing against the tracks.

The thing about catastrophes is that you can never seem to look away, their beauty so alluring. So you watch the train head for an impending disaster, mouth agape. It is only when you reach the book’s ending that you find out if the train crashed at all or, despite it being impossible, survived. And that task I leave to you.

The book does not just contain an answer to the train’s end; it also holds the explanation as to whether the train was Rani, or Nazo. Curiously enough, for every reader, the person embodying the train will differ and so will the choice to either wish the narrator dead or admire her guts.

The book depicts two different scenarios side by side: the trial against Nazneen Khan for Rani Shah’s murder, and Nazneen recounting her life chronologically, from her first meeting with Rani up until her death in the bombing at her rally. The story has a mundane start: Rani is portrayed as an enthusiastic politician with a desire to become the country’s Prime Minister and Nazo approaches her following an escape from the jihadists who had murdered her family before her very eyes. The subsequent chapters follow Rani as she prepares to run in the elections for the PM in New York with Nazo hell-bent on helping her in whatever way she can.

For me, the story turned interesting when Rani, upon her arrival to her native land, was welcomed by an attack from the jihadists. Thus followed a complex story with a number of players manipulating each other, every character trying to grasp the maximum amount of power. Rani and Nazo begin their journey as employer and assistant, and end it with the duo entangled in a battle of love and attention.

True to her promise made in the book’s blurb, Sabyn’s story portrays the country as a place infested with fanaticism and patriarchy, although set in a fictitious background. The setting’s description presents a dichotomy with the present occurrences in the country. Sabyn’s version of Pakistan is inhabited by a jihadist group influencing every political decision made by the leaders, much like the 1980s version of Afghanistan.

In what can be construed as either a bold or an outrageous attempt to appear passionate about women’s rights, the author shows the female population as greatly oppressed, subjected to dress a certain way and behave a certain way. The biggest focus is on the fact that no woman can attain education or leave her home sans a burqa or a male companion.

Though I admit it became disconcerting as the story progressed, I found myself formulating any logic behind Sabyn’s refusal to name the country the story was set in. Apart from the fact that the country was populated by Muslims and Rani mentioned going to the Metro City, there is no way to pinpoint where the story occurs. It was crucial to give Rani a reason to appear as an invested leader and what better way to do it than showcase a country ruled by a jihadist regime, with women having no say whatsoever in any matter. It helped put Rani in a much better light as she constantly campaigned to free the women of the societal boundaries and help them claim their right to education.

Nobody Killed Her is a low-key dedication to Benazir Bhutto, the first Prime Minister of Pakistan. I feel that we appreciate our leaders less than we should; hence a reason to like this story. It is futile to consider which leaders were more corrupt or which were less invested in the country in reality considering Sabyn tried her level best to depict a PM this country could have in real life. What she also managed to do was explain how power saps the faith of any well-meaning person and forces him/her to make choices they would never have made otherwise.

She also succeeded in building up Nazneen’s character from a meek assistant to a woman eager to help the women of the country although Nazo’s lust for attention had us reading about a number of heart-breaking events, some of which sadly include violence and graphic scenes, making this story one that cannot be stomached by the faint of heart.

I would like to add that a few of them had me question the lengths Sabyn had gone to show how Nazo was drunk on power, least of which include choices concerning children’s well-being. It was her irrational beliefs, including her utmost trust in Rani’s capability to be the leader she had promised to be, that had her commit her most heinous acts, or in some cases, only pray for the heinous act to commit itself.

Finally, the trial against Nazneen takes a shocking albeit somewhat unrealistic turn, which had me gripping the edges of my seat, and ends with a twist I did not expect. Although the conclusion appears a mixture of Bollywood thrills and clever planning, it still had me excited enough to both curse the story’s characters and marvel at how Sabyn was able to pull it off. A female PM rises as a hope for those without a voice in the heart of a country ruled by politics and army marshals and abandons her throne after being played as a puppet, betraying and being betrayed by those around her, experiencing the worst of tragedies and ultimately dying as a hero for those who made the mistake of believing in her, especially the one she both loved and hated the most throughout the story, her companion, Nazneen Khan.

And this is the reason why this book is the perfect summer read for every book lover out there.