What happens to such innovative, albeit small, engineering marvels beyond these exhibitions

Last month I happened to visit the All Pakistan Science Festival that’s an annual affair at the University of Engineering and Technology (UET), Lahore.

I was glad to see participation from kids and young adults alike; they had come from different parts of the country. I was even gladder at the incredible creations on display. And I couldn’t help asking myself as to what happens to such innovative, albeit small, engineering wonders beyond these exhibitions. Do their creators see the consumption and feasibility of their works in the big, bad, and highly competitive, commercial world out there? Are they actually seeking to develop their future projects beyond the blueprints? How do they hope to go about it all?

At a table close to where I was standing, I saw three young boys who were raring to explain the purpose and utility of a gadget they had made with "some LEDs, a transistor and a battery." They had named it ‘Simple Wireless Electricity Transmitter.’ "It works on the principle of Electromagnetic Induction," explained one of them.

At some distance, I came across a group of kids whose table had a board that said, ‘Gyroscope.’ This looked simple but eye-catching. I was told that it’s a "device for measuring or maintaining orientation, based on the principle of preserving angular momentum."

I stepped out of the venue, still thinking about the brilliant pieces I had just witnessed. Every year, our science colleges and universities turn out students who are brimming over with ideas to revolutionise the world. Hira Jabbar, a fresh Computer Engineering graduate from a local university, hopes to "grapple with the helplessness of the deaf-and-mute." She has developed an app (or application) which she says can convert sign language into spoken language.

"It’s still in its infancy," she tells me. "Its true implementation may take years as the project involves several modules."

However, she admitted that without proper funding, the idea may never see itself through.

This dilemma is commonly faced by the educated and ambitious youth of our country. Of course, every student I met (at the festival) expressed their gratitude to their respective institutions for providing them with lab and other facilities. But, financial help -- a grant, fellowship or the like -- is what everyone said they would need in order to take their projects forward.

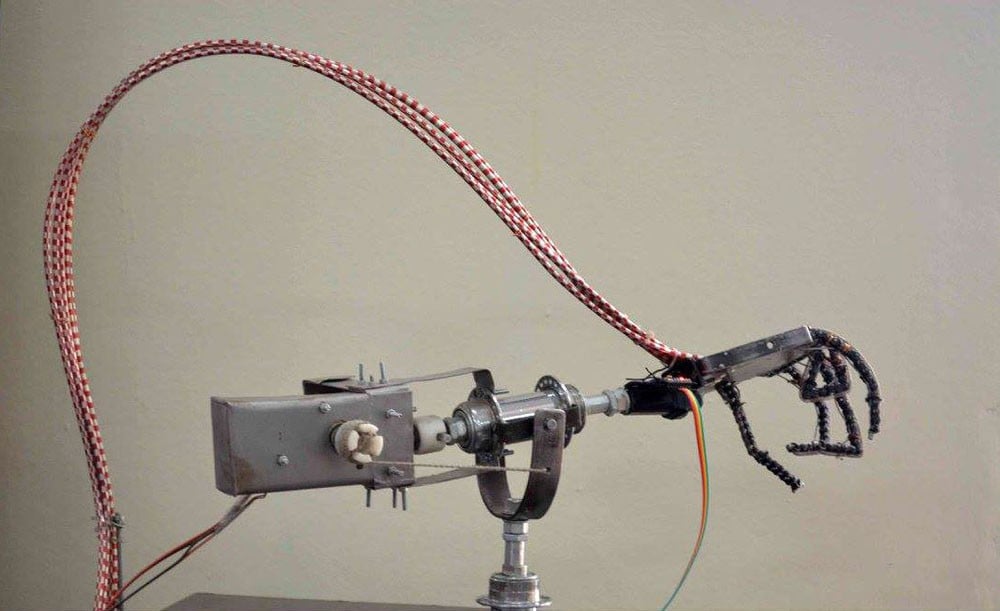

Shahzaib Aslam, a more recent UET graduate, had showcased this "multi-purpose robot that learns from demonstration. It records every gesture of the user and replicates it." I thought his project deserved more than just appreciation. Again, Aslam feared that scarce research opportunities and lack of financial aid might hamper his progress.

An international survey suggests that the Cambridge University, UK, has a research endowment fund of €3.9 billion, while Oxford University has €4.3 bn, and America’s Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has $13.5 bn. Even in our neighbouring India, the Delhi University offers different research programmes on subsidised rates.

Pakistan is lagging far behind. Though, things might be looking up. Shahid Munir, Director for Center of Coal Technology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, claims to provide the students funds and grants for their projects. For MPhil students also, the Higher Education Commission (HEC) is said to come forward.

Munir speaks of a Research Endowment Fund that should be developed by universities in order to finance the research projects.

Another factor that doesn’t let the budding projects see the light of the day is the ever-widening gap between academia and industry. Usman Ahmad, Assistant Manager, Maintenance and Projects, Panther Tyres Pvt. Ltd, rightly says that the CEOs of various companies have a conventional mindset, "They aren’t ready to bring about any changes in the system. Consequently, the creative minds are forced to replicate the tasks that have been in practice for ages, in order to keep the ball rolling.

"Since research does not find its application in jobs and industry, this makes our engineers trade their innovative abilities for meagre sums of money."

Munir proposes the idea that the universities convening career fairs should "invite industrialists to suggest ideas for research projects in accordance with the needs of the time. This way, the hard work of the researcher can bear fruit for the industry and the common consumer can benefit from it too."

He further says, "The universities should develop incubation centres, and industrialists should be made a part of the boards of studies."