Watching an NDTV interview with Arundhati Roy on YouTube about her long awaited second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, I can’t help but notice that the first comment below it, the one with the highest number of likes, simply says, "Send her to Pakistan."

To explain that remark, a little context. Twenty years ago Roy was working as a screenwriter for independent Indian cinema when she wrote her first novel, The God of Small Things. Her fiction was given astounding international reception, it won The Man Booker Prize and was translated into 42 languages. But immediately afterwards, she vocally gave up writing fiction to address reality. As an activist she took up a number of contentious causes which went against Indian nationalist narratives. Like Kashmiri separatism and the Naxalite-Maoist movement from West Bengal. She also took up environmental causes, wrote scathing essays on politics and capitalism, and how the former was more and more derivative of the latter, with corporate interests dictating public policy.

She became a celebrity activist, an immensely popular woman, the face of political liberalism in India; a face that became recognisable outside of South Asia too, in some instances perhaps even more so. She’s met with and written on the NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. She’s critiqued the American invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq.

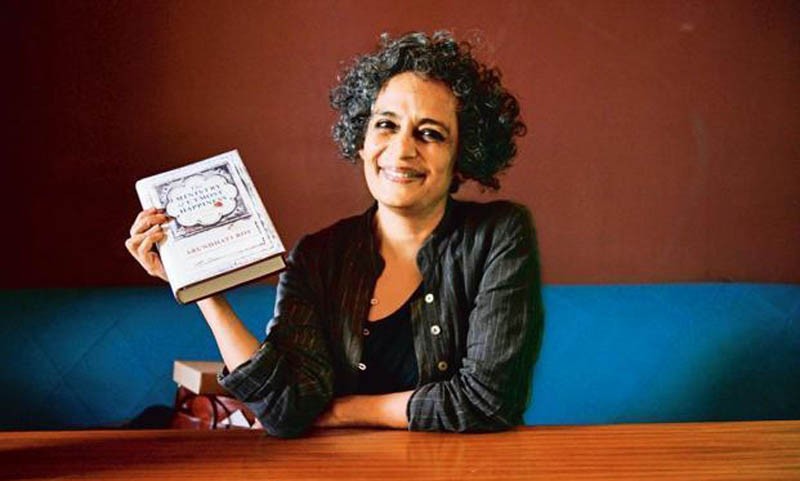

All of this meant that by 2017 she was in equal parts deified and vilified. Some years ago she went back to fiction, or as she says in the NDTV interview, "Fiction came back to me". She started a new book which was published earlier this month.

The release of this book has been met with more fanfare than any single piece of literature in South Asia. She has already completed book launch tours of the UK and the USA, given interviews, done meet and greets, book signings and readings in front of live audiences. Everywhere from universities to libraries to official consulates; from Los Angeles to London, from Harvard to Cambridge. She’s been reviewed in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian and a hundred other publications. The Atlantic calls it a "fascinating mess".

The book has been reviewed so extensively that there are now reviews of the reviews; in Scroll India and Outlook India commenting on how divisive the reviews are; and this one in Dailyo critiquing how reviewers are looking to pick apart her personal life and the 20-year wait instead of analysing the book, that separation of author and text made sacred by postmodernist thought.

In an interview published in The Guardian, before the book’s release, she says she sat down with her literary agent one day to discuss which publishing house to pick for her sophomore manuscript. She was, after all, one of the most sought after writers in the world. The offers were lavish and abundant. She is quoted as saying she let her characters decide which publisher to go with. She talked to the characters of her book and they settled on Alfred K. Knopf. This bit of prerelease hijinkery also got her a lot of press.

For a woman who’s become a living, breathing myth, conscious marketing gimmicks seem an unlikelihood simply due to a lack of necessity. Would it have mattered had she not said her characters lived with her and she converses with them all the time? Would it have meant that the book would not have made it straight to the bestseller shelves? I doubt it.

In a sense the phenomenon that is Arundhati Roy was fomented when Penguin India became the first international publishing house to open its doors to the second most populous country in the world, an explosion of English language publications and publishers followed, by now India is the second highest producer of English language books, right behind the United States. So Roy is not so much as marketing her book as fulfilling obligations of demand and supply.

We only have to look at our own country by way of comparison. Unlike India where the adult literacy rate is higher and English-medium education more accessible, our English speaking, or more importantly reading, middle class is restricted to a handful of cities. Even though a lot of money is being put into literature festivals, book launches remain confined to the smaller halls, or in some cases, out in the sun under an umbrella. There is little fuss, certainly no television interviews. The festivals themselves are increasingly becoming more about politics than literature. Perhaps because our urban middle class likes to talk more than it likes to read.

Nadeem Aslam, an accomplished writer of Pakistani origin who published his fifth book this year, called The Golden Legend, never even came to the country of his birth, where the book is set, to promote it. The most critically acclaimed English language writer in Pakistan Mohammed Hanif’s own second novel, Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, was well-reviewed at home and abroad, but he didn’t go globetrotting on a promotional rollercoaster.

So has Roy sold out to corporate interests in touring the world for her book, or is she simply making sure that people pick it up and read it, and love it or hate it but talk about it. After all, isn’t that the point of books, to be read, to evoke emotions and stimulate thought?

There is another immensely popular writer in India these days. Unlike Roy who waits for fiction to come to her, he goes to fiction with a sickle and hammer himself; he has churned out seven books in 13 years and is working on an eighth. He is reportedly the bestselling English language author in India. Here in Pakistan you might not have read him, but you’ve probably seen his works transposed onto the cinematic screen. 3 Idiots, 2 States and now Half Girlfriend. In all likelihood, Chetan Bhagat can now sell the film rights to his book before it’s even written.

Back in 2004, Bhagat hired a Public Relations firm to promote his first book, Five Point Someone, independently of his publisher, Rupa. Bhagat was an investment banker and had the personal wealth to do so. In his many sermons about marketing since then, he’s touched upon the same postmodernist dilemma mentioned earlier. Publishers promote books, but he believes in promoting authors, in his case, himself.

Places like Amazon India and dedicated bookstores preorder a certain amount of books given how they are expected to sell. By turning an author into a brand you can guarantee a higher number of preorders, even if reviews, subsequent sales and additional orders number poorly. Bhagat is not ashamed of his self-promotional strategies, which include newspaper and online advertisements with his face plastered all over them and his brand logo of being India’s bestselling author in boastful accompaniment.

But the sizable English speaking middle class in India doesn’t seem to mind this at all, postmodernism be damned. Chetan Bhagat has turned literary marketing and promotion from a publisher’s headache into a personal competition. Perhaps he’s part of the natural evolution of English language publishing in South Asia, as it’s making the journey from niche to populist. His number crunching obsession with preorders has also opened a window for first time authors, even from Pakistan, to market themselves well and make a few ripples in the literary pool. So 20 years on, in an entirely different publishing world, I think Roy can be forgiven for attempting a big splash herself.