A week of wandering through museums in Berlin to explore public history

Holding heavy histories and undecorated truths, Berlin’s urban landscape is imprinted with memories of various events, wars, movements, and everyday life in 20th century Berlin, including the Third Reich (Nazi Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). Opposites collude at these sites of imprints which embody tensions that are harder to uncover in history textbooks: of trauma and beauty, of the mundane and the unusual, of domination and resistance, of loss and love, of craftsmanship and mechanical reproduction, of the untold and the recounted, of life and death. Spread across the city, these sites foster public engagement with the past and offer quiet moments for critical reflection on history.

I arrived in Berlin on May 14 with an overly ambitious week-long itinerary that listed museum after museum and a tattered Lonely Planet paperback. I was most excited about the art, and Berlin is home to some of the best collections in the world. I was second most excited about the cafes, and late May allowed me to spend hours sitting outside, soaking up the sun and the city between sips of cappuccino.

Judging by the throngs of German students I saw in nearly every museum I visited (there were significantly more German students than tourists with fanny packs), an active engagement with history is a serious project in Berlin, and much of it takes place outside the classroom. It isn’t some surface-level project either: check out all this public history and have a juice box with a slice of nationalism. Instead, young learners ask questions and teachers welcome these questions and engage in sincere dialogue.

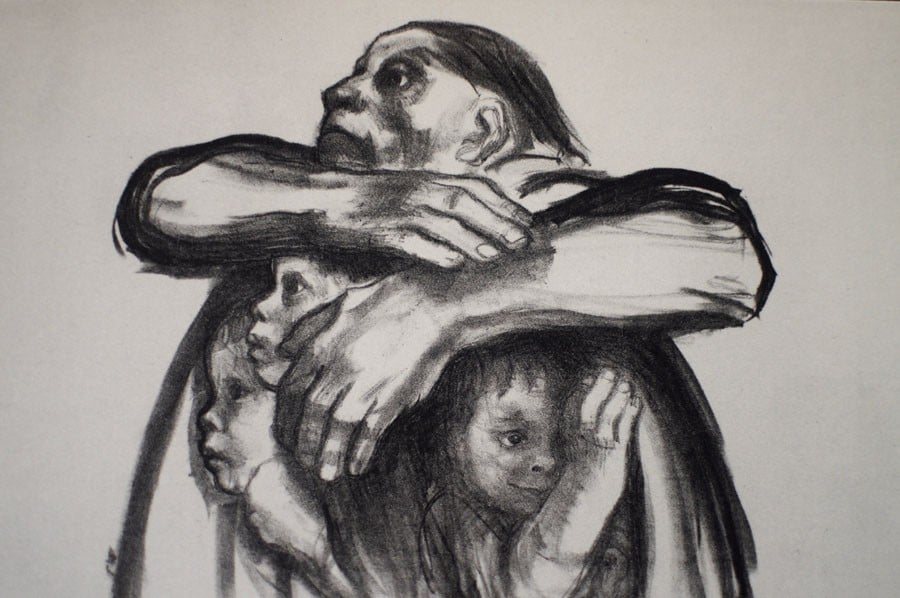

Of all the museums I had listed in my itinerary, I was looking forward the most to the Käthe Kollwitz Museum which houses the largest collection of Kollwitz’s work (1867-1945). I was first introduced to Kollwitz in a drawing class I took in college, and her stunning line work has haunted me ever since. Her subject matter deals with the stories left out of larger historical narratives, stories of working class families, motherhood, women, children, labour, hunger, and death. So when I came across a group of first graders sitting around and discussing Kollwitz’s final lithograph, Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground, I was a little surprised -- it seemed like a pretty intense Tuesday morning lesson for seven-year-olds. I can’t be certain of what was talked about since instruction was in German, but I did notice how the students raised hands to ask questions, demonstrating genuine engagement with the image in front of them.

Engaging with history is as much about the present as it is about the past and Kollwitz’ drawings, prints, and sculptures offer more than glimpses into the lives of the proletariat of the 20th century -- they depict the eternally recurring themes of loss and love -- she expertly illustrates both the clasping embraces of love and the grasping clutches of death.

After a long morning spent at the Gemäldegalerie (which holds an extensive collection of European paintings from the 13th to the 18th centuries), I grabbed lunch under the impressive canopy at the Sony Center and proceeded to wander the Potsdamer Platz neighbourhood. It started to rain when I caught a glimpse of a sign ‘German Resistance Memorial Center’ and followed a group of high-schoolers into the courtyard. The Memorial Center wasn’t on my itinerary but I’m glad the rain led me inside.

Located in the historic section of the former headquarters of the Army High Command, where Claus von Stauffenberg and other conspirators attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944, the Memorial Center houses an exhibit that documents the history of the individuals and groups who resisted against Nazi Germany. These resistors include military and political figures in addition to students, artists, publishers, and workers in the labour movement. This exhibition is critical because examining resistance is key to understanding how power operates. Why and in what ways did certain individuals or groups resist? How did these individuals resist becoming subjects of Nazism? And why was there no united resistance movement in Germany? We must continue to confront history and ask questions that are just as significant to us today as intolerance spreads and states and societies continue to violate human rights. What does resistance look like today? How can we build stronger movements of resistance to protect the most vulnerable in our communities? And what can we learn from histories of resistance?

The intimate connection between the mundane and the unusual is manifested in the DDR museum -- not a museum dedicated to the popular video game of the early 2000s like I had first assumed -- but the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (Soviet occupied East Germany) during the Cold War Period (1949-1990). The museum houses a collection of seemingly banal objects, school books, talcum powder, a can of sardines.

However, the stories accompanying these objects are less banal, of rationing commodities and STASI interrogation. A recreated kindergarten classroom showed how individualism was discouraged through communal activities, including collective potty training! Collective benches required that everyone remained seated until the last child was finished.

These sites of imprints allow us to confront histories that may be traumatic, unpleasant, and not necessarily fit into a coherent narrative. Discussing the importance of public history, Paul Gardullo, Museum Curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture writes, "What we choose to save, recover, hold up to the light of day and remember IS crucial -- personally and collectively, unofficially and officially, for the body politic and for the soul."

Sites of public history are political because they serve to remind us that history may not fit into a coherently chronicled narrative, that memory is always mediated, and consequently, these ambiguities lead us to reexamine, to question, to engage with. It is important to do this work because the past is inextricably connected to the present. Our histories, as complicated as they may be, help us understand ourselves better.

More importantly, history helps us understand those who are different from us, and so really, a lesson in history is a lesson in empathy. And in Berlin, there is a history lesson imprinted at nearly every other step!