A look back at how Nehru toppled the first elected communist government in the world

It was an interesting year in 1957 in India. The people of the newly-formed Indian state of Kerala elected a communist government. It was one of the earliest elected communist governments, after communist success in the 1945 elections in the Republic of San Marino -- a small city state surrounded by Italy.

In 1957, the San Marino communist government collapsed and Kerala assumed the distinction. Thereafter the communists have remained in power in Kerala intermittently for the next sixty years up until now. Interestingly, communism and Marxism flourished in Kerala even after the collapse of communism in the USSR and Eastern Europe, and after its radical transformation in China.

It needs to be noted that the widespread inequality in Kerala contributed to the Communist Party of India’s (CPI) success in Kerala. It doesn’t mean that the other parts of India did not have economic inequality -- certainly they had -- but in Kerala perhaps it was more pronounced. One of the factors was a very high proportion of extremely poor agricultural workers in the 1950s, in contrast with exceptionally wealthy landlords. The main attraction was the promise of the CPI to distribute wealth more evenly. Then Kerala also had a sophisticated education system that flourished in the post-independence period resulting in high literacy rate in peasants and workers who were encouraged to engage in politics.

After coming to power in Kerala, the CPI further expanded the education system that led to the highest literacy rate in all of India by 2007. Despite high economic inequality, sectarian conflicts have been conspicuous by their relative absence. While the rest of India simmered with ethnic and religious violence, in Kerala it has been rare. Poor Hindus and Muslims have not been as divided in Kerala as in other parts of India, and this has facilitated various religious sects to cooperate politically among the lower classes of society.

Another factor that contributed to the rise of communism in Kerala was the persecution of communists in post-independence years that encouraged support for the Communist Party. Per some estimates, the Indian police killed thousands of communists, following the independence. This violence encouraged sympathy with the communist cause that was trying to secure minimum wage increase and other rights for peasants and workers. Communists opposed the powerful elites and won hearts and minds of the Keralites. Moreover, the communists had accepted the perception that in pluralist democracies, socialism could be established through a peaceful democratic process.

It may be recalled that by the mid-1950s, the democratic socialists had accepted universal suffrage as the right method, whereas the revolutionary socialists continued to press for organising violent revolutions. Discarding the earlier revolutionary zeal, now the CPI was also trying to bring about socialist reforms through democratically elected representative institutions. It was more like a Scandinavian model to establish a strong and stable welfare state.

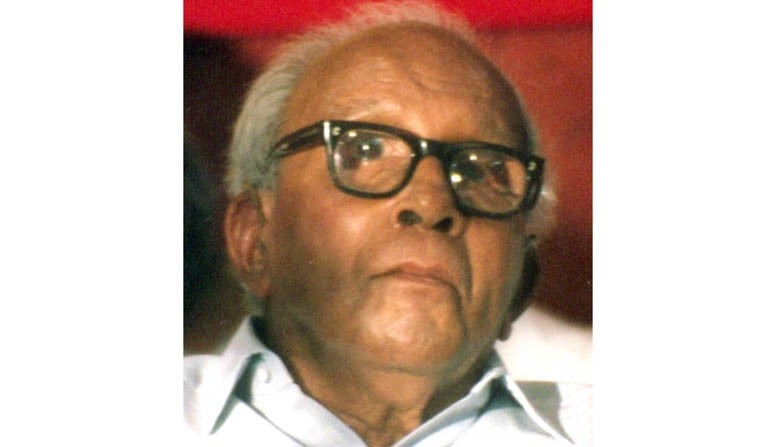

In 1957, the CPI won a majority in the state elections and formed the first communist government after assuming power. The communist leader, EMS Namboodiripad (1909-1998), became chief minister and set a new example for the communist parties in other Indian states.

He had the distinction of being the first non-Congress chief minister in the Indian republic. The bitter experiences of following a revolutionary road had greatly influenced the CPI and after participating in universal adult franchise under the new constitution it was ready to introduce a new approach and outlook. It concentrated its efforts to win the electorate and tried to become a partner of a healthy democracy. The first communist government in Kerala had the cream of the CPI in that region such as Goplalan, Damodaran, Namboodiripad and Achutamenon.

All big names, well-known in the communist movement across India, had participated in earlier popular struggles. After forming the government, they initiated thoughtful changes in state government policies from the angle of the poor. Two of the first progressive legislations introduced were the Land Reforms Act and the Education Act.

Now the question is why did they fail? One of the causes was the failure to draw a line between the party and the government. The party started interfering in the local administration, and the police itself resisted. Then there was widespread opposition to the Land Reform Act especially by vested interests.

Almost at the same time certain segments of society lined up against the Education Act too. Within two years all opponents began to converge and a ‘liberation struggle’ was launched against the communist government. This led to the dismissal of the state government that was elected for five years but could remain in power just for 28 months. Somehow, the landlords could build a movement that appeared to have support mainly against the Land Reform Act and the Education Act. The government was dismissed in 1959 while it still enjoyed a majority in the Legislative Assembly. The dismissal was initiated on the recommendation of the governor of Kerala.

Why did Nehru, the prime minister of India, and a loud preacher of democratic ideals, follow the recommendation? It was rumoured that Nehru was hesitant to dismiss a democratically elected government, but it was his daughter, Indira Gandhi, who persuaded him to make such a decision. Her authoritarian tendencies were taking shape to take full bloom when she became prime minister and imposed the state of emergency in 1975. In Pakistan, such dismissal had happened many times in the first decade after independence, and now India followed in the same footsteps. In both countries, they were clearly against the letter and spirit of parliamentary democracy.

Ideally, no government -- state or central -- should be dismissed while it enjoys a clear majority in the legislative assembly. But it goes to the credit of the political parties in both India and Pakistan that despite such dismissals, they have not diluted their commitment to electoral politics and parliamentary democracy. Namboodiripad remained a leading communist politician and theorist. During the 1962 Sino-Indian war, he did not join the bandwagon of the Indian jingoism, and that led to a friction within the CPI. In 1964, he led a faction of the CPI that broke away and formed a separate party called the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPM.

As the CPM leader in Kerala, he was elected again in 1967 to remain the chief minister for another just two and half years. This time around he became a victim of his CPI opponents who withdrew support to his coalition government. The CPI formed its own coalition government with Congress and remained in power till 1977. The CPI supported Indira Gandhi in her declaration of Emergency in 1975, whereas the CPM remained a bitter opponent to Congress. Namboodiripad was a Politburo member and general secretary of the CPM from 1977 to 1992.

He served as a member of the Central Committee of the CPM until his death in 1998. He also authored a notable book on the history of Kerala and always considered M K Gandhi as a Hindu fundamentalist. One wonders how many chief ministers in Pakistan have written any book on their province’s history or on any other subject for that matter; and how many can question the father of the nation as he did.