The mentally ill in rural and backward setups are often abandoned by their families at shrines, where they suffer at the hands of ruthless faith healers. This is where organisations such as MIND come in

It was a full moon on a Thursday night. Mooda (name changed on request), a middle-aged father of three, was acting crazy.

The neighbourhood in the katchi abadi where he lives, heard the cries of Shammo, his wife. Apparently, Mooda was beating her and their children in a brutal manner. Eventually, the neighbours interrupted, and saved the poor lady and the three little children from his wrath. Soon Mooda was calm. But this state of his wasn’t going to last.

As it transpired, the man was suffering from some sort of psychosis. He would have fits of mania and then he’d start behaving insanely and, as on that particular night, with violence. He was also known to doubt things, especially his wife’s character, and his suspicion was only becoming stronger by the day.

Mooda’s family, in their unblissful ignorance, believed he was under the influence of some evil spirit. One day, his father together with the brothers of Shamo decided to chain him, because they feared he might kill the family. They could not bring him to control his anger and aggression.

But chaining was not going to be a permanent solution, because Mooda was the sole bread earner for the family. So, they took him to the Data Darbar where he was drugged, while in chains, so that he could stay calm and the evil spirit could be shooed away.

They were at the shrine for three days, waiting for a miracle to happen. But they had no idea that it was a disease that called for clinical treatment.

At the Darbar, someone suggested to them to visit MIND, a non-profit organisation that works for the mentally challenged, especially those abandoned by their families. It also works to promote awareness about mental health issues to reduce stigmas attached to them.

Luckily for Mooda, his family understood the need, and took him to the organisation where he was given free medication and treatment.

Mooda was stable within a few months’ time, and his mania began to subside. Though, he couldn’t remember much about the times he was ill.

Mooda is not the only one to have gone through whatever he did. There are many mentally ill people out there, in rural and/or remote setups, who are left to suffer at the hands of ruthless faith healers. Not everyone is lucky enough to get the right guidance.

Dr Saad B Malik, President, MIND Organisation and Head of Psychiatry Department at Shalimar Medical College, Lahore says the charity engages volunteers among doctors -- mostly psychiatrists -- who visit the shrines routinely and look out for such patients.

"It often involves the risk of retaliation from faith healers or custodians of shrines, so we first speak with the locals and approach the patients with their support," he tells TNS.

"Many patients are bipolar or suffering from anxiety and panic disorders, clinical depression, schizophrenia, or some other psychiatric diseases but they are perceived to be victims of black magic which is brought to them by someone with evil intentions.

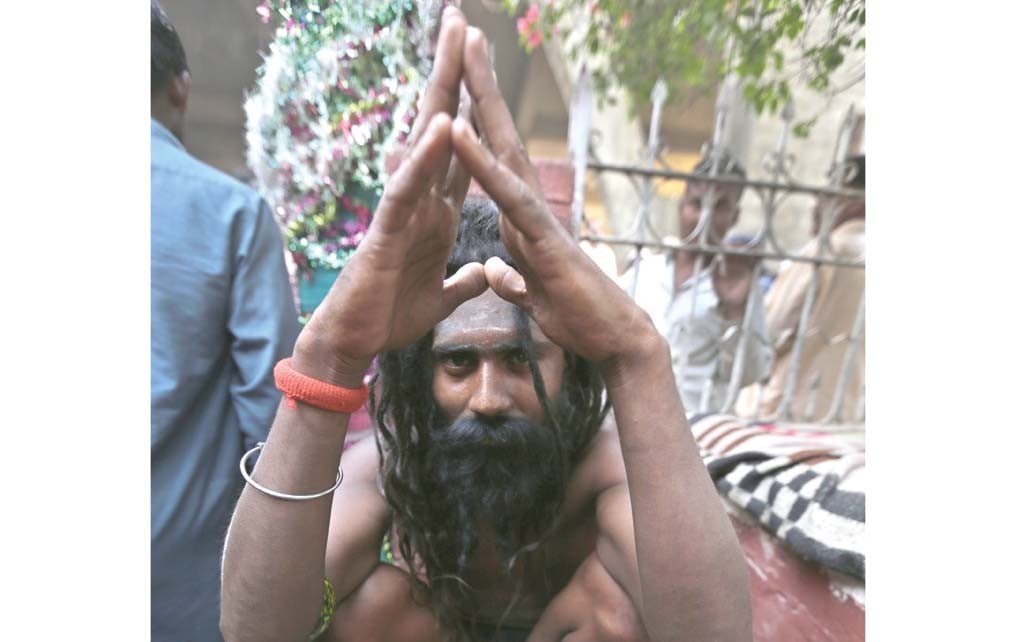

Malik says that such people are dubbed "Saeen" or "Majzoob," meaning those who are absorbed in the love of God and the saint at the shrine, and have nothing to do with the mortal world. "In rural areas, these patients are sometimes even hung upside down from trees and exposed to smoke rising from the ground below."

Malik recalls how once a team of doctors and psychologists visited a shrine in Burewala. They were shocked to see a number of psychiatric patients who had been tied with chains to the trees in the courtyard. "The doctors set up a makeshift clinic, next to the shrine, and a local practitioner was hired to conduct a tree-to-tree round of these patients who were then provided with medication and psychiatric care on location, free of cost.

"The guardians at the shrines were initially distrustful of the team, but soon they started to cooperate with the doctors and allowed them access," he adds.

There are more gruesome practices reported. In Hafizabad, it was found that bloodletting was a common ‘treatment’. Precaution was taken while removing the blood of the mentally ill. MIND set up a clinic there as well.

Dr Malik says that a team consisting of four psychiatrists, a multipurpose worker, and an administrator now visits Hafizabad once every fortnight and provides free consultation and medication. "The organisation [MIND] also holds awareness campaigns at the shrines, educational institutions, prison houses etc. We tell the people that these illnesses need serious treatment. If left untreated they aggravate fast and can result in further complications."

Dr Izharul Haq Hashmi, Director, Fountain House, acknowledges the seriousness of the issue and laments the absence of a proper programme to help those abandoned at shrines. "At the mental hospital, we take extreme cases," he says. "However, in Karachi, Darul Sakoon is working for the welfare of the shelterless among the mentally challenged. It not only puts them up but also provides them with proper treatment."

Hashmi reveals that the Fountain House administration has decided to construct four such places in Farooqabad that will take in 40 females each.

Tahir Raza Bukhari, Director General (DG), Auqaf and Religious Affairs, Punjab, rejects the report of MIND Organisation, saying that the department keeps a close watch on what is happening at the shrines. "We make sure no mentally challenged person is left at a shrine. Our culture is strong and families like to take care of their own people."

Bukhari also blames MIND for having "vested interests… just like any other NGO. Its purpose is just to receive donations from the West."