In an important book, Nasir Abbas Nayyar replaces the stereotypical image of a dirty, uncouth bohemian with that of a modern man and poet

Nasir Abbas Nayyar has shaken the scene of Urdu literary studies with his unique interdisciplinary approach, just as young Wazir Agha did more than 60 years ago when he applied the Jungian theory of collective unconscious to analyse some pieces of Urdu poetry. While Agha’s work was single-layered, straightforward, and easy to comprehend, Nayyar’s approach is multilayered, complex and much more challenging.

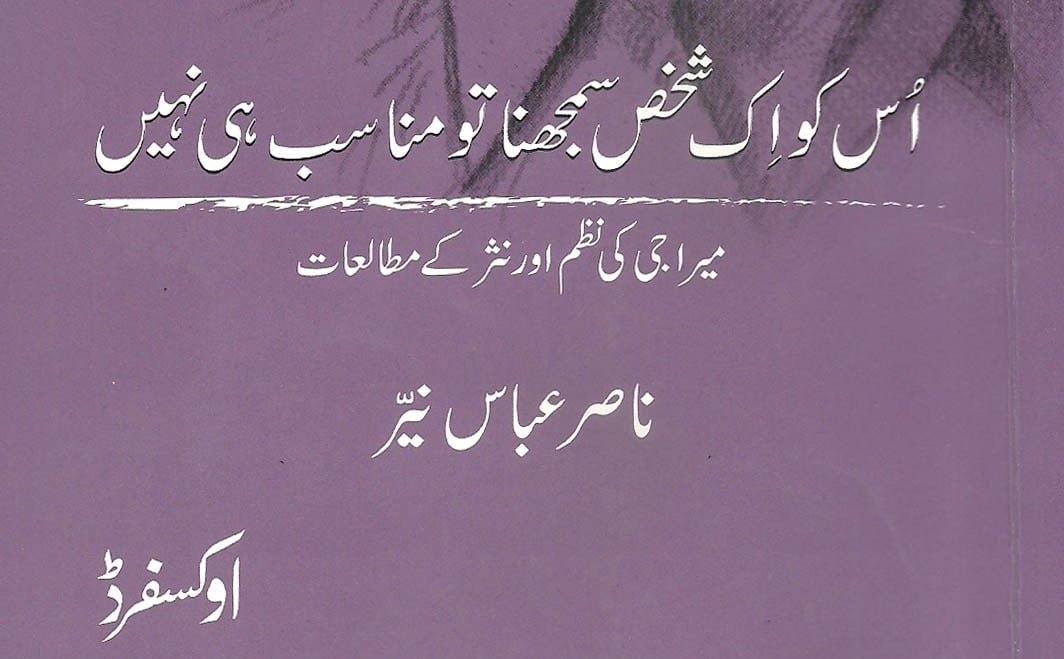

Nayyar is the pioneer of postcolonial studies in Urdu and has written extensively on the poetics and aesthetics of Postmodernism. The book under discussion, Ussko Ikk Shux… is a thorough study of Meeraji’s poetry, prose, and his remarkable critical vision.

Meeraji’s dominant image, unfortunately, has been that of an unkempt man, with an outlandish dress sense, long and floating hair, a dagger-like moustache, big earrings, colourful headgear, an amulet, a string of beads around his neck and most notoriously, three small balls in his hand -- like the ones used by jugglers -- wrapped in thin silvery foil.

Manto’s sketch ‘Teen Golay’ (The Three Balls) enhanced and authenticated this image in such a powerful way that all efforts of Altaf Gauhar and other fans of Meeraji failed to undo this bohemian mask in order to bring out Meeraji’s real face.

Gauhar, the young bureaucrat, was perhaps the first person who in the early 1950s, made many sincere efforts to evaluate Meeraji’s poetic skills, independent of his physical appearance and personal eccentricities. In later years, Zia Fatehabadi, Shafey Kidwai, and Rasheed Amjad contributed valuable material to the subject. But Nayyar’s present work is the first attempt to see Meeraji’s poetry and prose in a postcolonial perspective.

As a critical theory, postcolonialism presents, explains and illustrates the ideology and practice of neocolonialism. It also examines the effects of colonial rule on the cultural aspects of the colony.

In the first chapter, the author explains the modernity of Meeraji with reference to his poem, ‘Silsila-e-roz-o-shab’. He distinguishes ‘modern’ from ‘modernist’: any liberal and enlightened person of a given era in human history can be ‘modern’ in the context of that particular period, but being ‘modernist’ is a purely 20th century phenomenon. The modernist walks on the tightrope of the present moment, step by step. He comes out of the darkness of the past and enters into the misty, foggy future; the only bright spot being the present moment.

The modern man’s dilemma is that on the one hand he wants to cut off from the past, and on the other -- to interpret the intricacies of the ethereal present moment -- he takes refuge in the distant past where mythology is king. Here the concepts of duality and synchronicity pop in and the author deals with them masterfully.

The second chapter is devoted to analysing the problematic relationship between modernity and mythology. Referring to various modern Urdu poets, Nayyar tells us that from Meeraji, Rashed, Munir Niazi, Agha and Gilani Kamran to Sarwat Hussain, Afzal Ahmed Syed, Satya Pal Anand and Ali Mohammad Farshi, every modern poet has been using myth in some form or the other. The reason being is that myth itself was a product of poets’ fertile imagination, especially for poets of the classical era. Greek mythology first appeared in Homer’s Iliad and a big bulk of Indian mythology is derived from the poet Valmiki’s Ramayana.

Meeraji not only fully utilised the force of myth in his poetry but also defended it robustly when the Progressives attacked such poetry in the name of Realism.

In the third chapter of Nayyar’s book, Meeraji’s long poem ‘Ajunta kay Ghaar’ (The Caves of Ajunta) has been analysed. These caves were developed, and decorated with religious carvings 2,000 years ago for Buddhist monks, but Meeraji visits the site neither as pilgrim nor as tourist. He looks into these caves with the eyes of "a modern man from the colonial sub-continent".

The fourth chapter is a detailed structural analysis of Meeraji’s poem ‘Sumandar ka Bulava’. Before we proceed, let us have a look at the beginning of this poem:

Call of the Sea

These murmurs are saying, "come along,

Calling you for years has wearied me to death"

I have heard voices, briefly, or for longer,

But this strange one is new.

Calling never wearied anyone, and perhaps never will.

"My darling child" "Oh, how I love you" "I’d go mad

If ever you did that" "Oh my God"

At times a sob, a smile, or just a frown

Those voices are my old familiars,

They have joined my brief life with eternity

But this strange voice, wrapped in total weariness,

Threatens to drown out all other voices

(Translated by F. Pritchett)

Nayyar has chosen this poem for a complete structural analysis because, in his view, this poem can be taken as the prototype of modern Urdu poetry.

In the next chapter, Nayyar discusses Meeraji as a critic and talks about his psychological method and other tools of analysis.

The last chapter is about Meeraji’s translations, and by the time you finish the book, the stereotypical image of a dirty, uncouth bohemian starts to fade out, and is replaced by a new smiling face of a soft-spoken modern man. This emerging face is the one that will permanently stay in your memory.