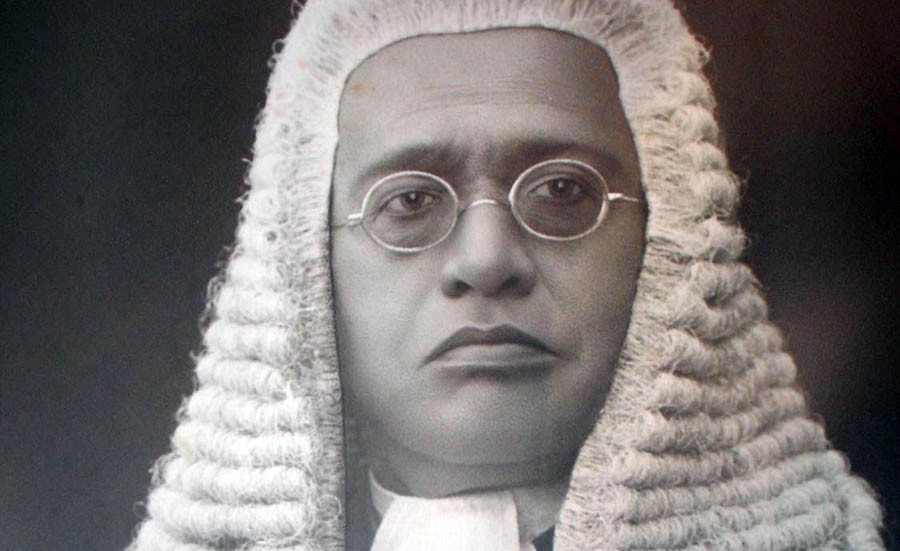

A landmark epoch in the history of judiciary in South Asia

Sensing that his legal acumen was more useful on the bench of the Punjab Chief Court than either the bar or the legislative council, Rai Bahadur Shadi Lal was elevated to Punjab Chief Court in 1913 as an additional judge by the government of India. Thus just after he turned forty -- an age when usually people are just making their mark in one profession -- Shadi Lal had proved his mettle in different arenas and was now poised to make history in the judicial annals of the country.

Early in his career on the bench, Shadi Lal made his mark in the interpretation of customary law and then commercial law. At that time, commercial law was something new to the province as industry had just picked up at the turn of the century. So having a judge well-versed in commercial law to act as company judge was a benefit in the court so that proper adjudication of disputes could be made.

In terms of customary law, one of his important judgements was in Ghaus v. Faji (1915) when he decided that the conversion claim of a party should be taken in accordance with the actions of the party, rather than circumstantial considerations. He wrote: "the courts of law have no other means of finding out a person’s intentions than that indicated by his acts and conduct and the present case, though the matter may excite suspicion, there is nothing to show that Fajji’s change of faith was not genuine."

These and other judgements exhibited the sound legal mind of Shadi Lal and after serving several terms as temporary and additional judge of the court, he was made a permanent member of the bench in 1917.

At the time of the sudden demise of Sir Henry Rattigan in 1920, who had been chief justice of the Lahore court since 1917, Shadi Lal was the senior most barrister judge in the Lahore High Court. At that time, the tradition in India was that chief justice was chosen from among the barrister judges of the court, so that not only legal soundness could be ensured, but a clear separation between the judiciary and executive be made visible.

However, 1920 was not a very peaceful year in either the Punjab or India. The Great War had only recently ended, and the new Government of India Act 1919 had just introduced diarchy, with responsible Indian ministers in the government for the first time.

Read also: Rescuing Sir Shadi Lal

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre had also just taken place in the preceding year and very soon the Indian National Congress and the Khilafat Committee were going to embark on the first all-India anti-British protest movement under the Khilafat -- Non-cooperation Movement. Hence, it was not seen as a time for the introduction of further changes in either the province or the country.

Despite the precarious situation in the country and the province, it was patently clear that only Shadi Lal could be made the Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court in succession to Sir Henry Rattigan. Shadi Lal’s legal acumen was well regarded by all the communities in the province and even his British colleagues and the government held him in high esteem.

Hence, in May 1920, the Lahore High Court made history and the first Indian was elevated to the high office of Chief Justice -- not even the earlier presidency courts, or the Allahabad High Court, had the distinction of breaking through this glass ceiling, and only the Lahore High Court, achieved this singular distinction.

Shadi Lal (knighted in 1921) presided over the Lahore High Court for fourteen years -- the longest tenure yet of any Chief Justice, and he arguably presided over a difficult period of the court. It was during his tenure that the Freedom Movement picked up, and it was during his time that the politics of India became increasingly communal.

In these tense years, Sir Shadi Lal had to ensure that the high court kept itself above politics and upheld the rule of law despite several drawbacks. Hence, it was in his tenure that the high court not only had English judges appointed, but also several Hindu and Muslim judges, and even the first Sikh and Indian Christian judges were appointed.

While diversity in the bench mattered to Sir Shadi Lal, the primary consideration was merit -- he would not appoint a judge simply because of his religion or ethnicity, he also had to be an exceptional jurist. All sides of the spectrum appreciated this even-handedness of Sir Shadi Lal, where at times a community had to wait for a judge to be appointed, but they were sure that the appointment, when made, would be on merit and would add to the distinction of the community.

Similarly, be it a case where the executive was involved, or where different communities were at loggerheads, Sir Shadi Lal’s sole criterion was the letter of the law and nothing else. In one instance when one member of the executive tried to exert his influence over the court, Sir Shadi Lal contended that if such an effort were ever repeated he would not hesitate to issue a notice of contempt no matter how exalted the functionary was -- needless to say, the executive functionary never returned.

Sir Shadi Lal was also very even-handed in his use of the wide judicial powers granted to the court. In terms of contempt notices, which had become frequent earlier, he cautioned his brother judges to use them sparingly. In one case, for example, Dalip Singh v. Emperor, he noted: "the question is not whether the Court felt insulted, but whether any insult was offered and intended. A judicial officer has no doubt to maintain the dignity of his court, but he must not be too sensitive, especially when his own action is not altogether justified." His even yet firm handedness prevented the court from getting politicised and maintained its dignity.

Sir Shadi Lal’s tenure was a landmark epoch in the history of the judiciary in South Asia. When he retired in 1934 upon reaching the age of sixty, he was given the further dignity of being elevated to the Judicial Committee Privy Council where he sat as a judge from 1934 to 1938. Commenting on his legacy his biographer, K.L. Gauba, wrote:

"Apart from some casual murmuring of disappointed claimants to the patronage of the Chief Justice, never during the long period of fourteen years, during which Sir Shadi Lal presided over the Supreme Court of the Punjab, was it ever breathed or whispered, or perhaps even thought that he allowed his personal views and predilections to weigh with him in the decision of the large volume of cases of all kinds that came before him, or in the appointment of benches or allocation of the court’s work. From 1920 onwards the High Court rose day by day in the estimation and affection of the people and to this tribunal resorted persons of all creeds and all means, convinced that if there was any merits in their causes, these would be weighed with measures as accurate as human intelligence could fashion them, that they would come before benches in the usual course, that no judge, far less the Chief Justice, in whom parliament had vested great powers and discretion in the constitution of the Courts, would predetermine a case….Never once was it suggested or one can safely say was it ever believed that there was a short cut to justice in the High Court…"

Sir Shadi Lal moved back to India in 1938 owing to ill health and then passed away in 1941.

Despite his exemplary career and despite the fact that he was lauded by all communities in the province and the country, Sir Shadi Lal has been lost in the Pakistan narrative. It is time that we recognise and celebrate all those who have served in this region, without reference to their religion, but keeping central their work in the progress of the country.