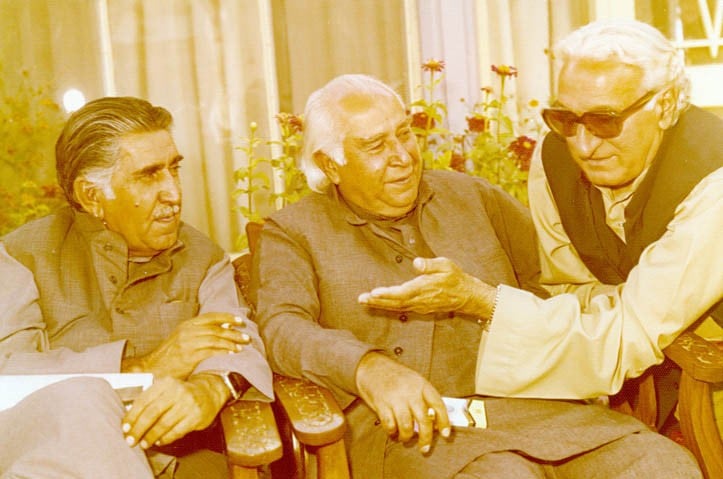

Half a century of democratic fights by Ghaus Bizenjo and Wali Khan contains some of the most important chapters of Pakistan history

Exactly 60 years ago, when the National Awami Party (NAP) was formed in 1957, it emerged as the most prominent progressive party in Pakistan. Though it had in its ranks political stalwarts such as Maulana Bhashani from East Pakistan, Mian Iftikharuddin and Kaswar Gardezi from Punjab, GM Syed and Haider Bakhsh Jatoi from Sindh, there were two relatively younger leaders from the NWFP (now KP) and Balochistan -- Khan Abdul Wali Khan and Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo. Both were 40 years old and still had at least 30 years of active politics to do before they retired after the general elections of 1988 and 1990 respectively.

This year marks the birth centenary of Abdul Wali Khan and Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, now nearly forgotten heroes of democratic struggle in Pakistan. Both fought against the British rule, tried to prevent the division of India, and briefly strived to get an independent homeland for the Baloch and Pashtun people. Once the division was sealed and Baloch and Pashtun areas were incorporated in Pakistan, both accepted Pakistan as their destiny and waged an unrelenting fight to establish a democratic order in the country.

Abdul Wali Khan and Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo were men of steel who spent substantial parts of their lives in jail, never accepted any ministerial positions, and never compromised with the establishment. Both had become active in politics in 1930s. That was the time when the freedom struggle was at its prime and peripheral areas of British India, Balochistan and the NWFP, had little or no say in the central politics being played in the regions such as Bengal, Gujarat, Punjab, and UP. The Indian National Congress -- the biggest and most widespread political party -- was also dominated by leaders mostly from central and south India.

But one leader who towered above many others -- Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, popularly known as Bacha Khan -- belonged to the Pashtun areas of the NWFP. He had transcended his peripheral origins to play a more active and progressive role not only in the northeastern part of India but influenced countrywide politics so much so that almost at parallel with Mahatma Gandhi, he was dubbed as the Frontier Gandhi. Wali Khan was his son and political heir who could never match his father’s stature due to the changing times and context, but still played an important role in the struggle for democracy.

Bacha Khan interacted with great leaders such as Gandhi, Nehru, Azad, and Jinnah; whereas Wali Khan and Bizenjo had to deal with smaller figures such as Maj-Gen Iskandar Mirza, General Ayub Khan, General Yahya Khan, ZA Bhutto, and General Ziaul Haq. The freedom struggle was much bigger in magnitude where the common people were involved in a war of immense proportions against a foreign establishment. After independence, a local establishment in Pakistan, supported by international imperialist forces, repeatedly crushed the movement for establishing democracy.

Wali Khan and Bizenjo had to reiterate their allegiance repeatedly to the country they wanted to emerge as a democratic republic and not as a Bonapartist state that the dictators made it to be. Those who sided with the establishment in the loot and plunder of the country never had any difficulty in getting recognition and rewards, whereas the fealty and integrity of Wali Khan and Bizenjo were under scrutiny throughout their lives, for they never compromised on the principles of democracy. Bizenjo had a youth different from Wali Khan in the sense that Bizenjo was a poor orphan child and never had the protective wings of a father such as Bacha Khan.

Bizenjo was a stout football player while Wali Khan suffered from health issues, including almost blindness in his one eye; but in their will to display courage, they were at par. Bizenjo completed his four-year tertiary education at Aligarh University. Unlike most of our present-day politicians, Wali Khan and Bizenjo were men of letters. Bizenjo’ s autobiography, In Search of Solutions -- a slim volume edited by BM Kutty -- is a treasure trove of information about the politics of Pakistan in general and of Balochistan in particular. As is the hallmark of most great men, Bizenjo and Wali Khan seldom talked or wrote about themselves.

Bizenjo’s biography is more about events and less about himself, but the pages where he describes his time in prison are fascinating. He is unapologetic about his initial desire to see Kalat as an independent country, but then also justifies his role as a patriot Pakistani to see this country embark on a democratic path. Both Wali Khan and Bizenjo were sincere with the people of Pakistan and tried their best to do a national-level progressive politics. Wali Khan was rewarded for his efforts immediately when he was imprisoned for full five years in the early 1950s, yet he never became a narrow nationalist.

The formation of NAP in 1957, and the part Bizenjo and Wali Khan played in it, was a clear indication that both did not want to confine themselves to Balochistan or the NWFP. In the planned general elections of 1959, NAP was expected to win comfortably with Awami League. Both were liberal, progressive, and secular parties that believed in minority and national rights and promised a democratic polity.

For the retrogressive establishment of Pakistan supported by the western imperialist forces, a progressive and left-leaning Pakistan was an anathema. So, the elections were called off and martial law was imposed with a complete ban on political activities imposed by Major General Iskandar Mirza and General Ayub Khan.

Bizenjo and Wali Khan’s struggle against the dictatorship of Ayub Khan was countrywide and they never minced their words in demanding a free and fair treatment for all nationalities in Pakistan. Bizenjo was imprisoned when a note was allegedly found on him saying ‘down with one unit’. He was subjected to severe torture. When General Ayub Khan was using the might of his civil and military bureaucracy against the democratic and political forces of Pakistan, Wali Khan and Bizenjo were in the forefront, fighting against despotism, while ZA Bhutto was still in lap of the generals.

When General Ayub Khan manipulated elections in 1965 to defeat Fatima Jinnah, it came as a big setback for the democratic forces in the country. In 1967, NAP split into two factions, led by Wali Khan and Maulana Bhashani. One of the reasons given for the split was Bhashani’s soft corner for General Ayub Khan and his pro-China leanings. Wali Khan and Bizenjo had no soft corners for dictators and sided with the Soviets in the Sino-Soviet rivalry of the left politics. The removal of Ayub Khan and the disbandment of the One Unit by General Yahya Khan paved the way for the general elections of 1970.

Bizenjo and Wali Khan led the progressive and nationalist forces while Bhutto was using the slogans of Islam and socialism. After assuming power in 1971, Bhutto retained martial law till April 1972. He reached a tripartite agreement with the JUI and NAP allowing them to form governments in Balochistan and the NWFP.

For the first and the last time, Bizenjo and Wali Khan led NAP to form governments. But within nine months, the Balochistan government was dismissed and the one in the NWFP resigned in protest; Bizenjo’s governorship of Balochistan also ended. Thus, began another period of democratic struggle by Bizenjo and Wali Khan against the highhandedness of Bhutto.

Despite being in opposition to Bhutto, Bizenjo and Wali Khan helped in the constitution making of 1973 and were key signatories to Pakistan’s third constitution. Their efforts came to naught when Bhutto himself starting subverting his own constitution. Bhutto’s onslaught culminated in his final blow to NAP when Bizenjo, Wali Khan and almost all major progressive and nationalist leaders were arrested and charged with treason. Bhutto banned NAP and the Supreme Court also conveniently snubbed it. That was the beginning of Bhutto’s own undoing that he had himself initiated by crushing the only national-level democratic, liberal, progressive, and secular party in the country.

Bizenjo and Wali Khan had been warning Bhutto against his excessive reliance on the security apparatus, telling him repeatedly both in and outside the parliament that democratic principles needed to be upheld and a healthy opposition was necessary for democracy to thrive. Bhutto’s dismissal in 1977 brought some relief to the duo, when General Ziaul Haq abolished the Hyderabad Conspiracy Case. But both Bizenjo and Wali Khan rebuffed all attempts of the dictator to entice them into his fold. The last major struggle waged by the two was against Zia, whose dictatorship was challenged by the Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD).

After the death of Zia, general elections were held in 1988 and Bizenjo had the shock of his life when a younger opponent defeated him. Already over 70, Bizenjo fell seriously ill and died in 1989. Wali Khan lost his seat in 1990 elections, and retired from active politics. His books, especially Facts are Facts, are works of painstaking research. Though he lived till 2006, his last years were unremarkable. Before he died, he had to see another army takeover in Pakistan by General Pervez Musharraf, but by then he was too old to wage another struggle.

Half a century of democratic fights by Bizenjo and Wali Khan contains some of the most important chapters of Pakistan history. Without them, our journey to democratic ideals would have been a mundane affair.