The best antidote to the populist onslaught is adherence to democratic principles

With the recent victory in the UP elections by the BJP, the populist Modi has adorned another feather in his cap. What populism is and how it is sweeping the world has already been covered in the pages of the The News on Sunday in an excellent article by Beenish Kulsoom on February 26, focusing mostly on the US and Europe.

Here the aim is to briefly highlight the populist politics in South Asian countries such as Bangladesh, India and Pakistan and look at how democracy can still be defended in the face of the populist onslaught.

Bangladesh -- called East Pakistan before 1971 -- was one of the first regions in the Indian subcontinent that produced a populist leader in the person of Mujibur Rahman in the 1960s. Though his supporters may not like to categorise him as one, many of his personality traits and political preferences make one think that he was more of a populist leader than a democrat.

It may be argued that most leaders of freedom movements in the 20th century were essentially populists but if you look at one major attribute of populism i.e. exclusionary politics, you realise that not all freedom fighters were populists.

In East Bengal, perhaps the greatest leader of the 1940s and 1950s was HS Suhrawardy but he can hardly be called a populist leader because he never did any exclusionary politics. He believed in inclusion of all in his Awami League and even accepted the Parity Formula in the 1956 Constitution just for the sake of democracy. He was a secular politician who did not target any nationality, ethnic group, religion, or sect -- a hallmark of most populist leaders.

Ultimately, his humiliation at the hands of General Ayub Khan led to his exit and paved the way for the populism of Mujib.

It was not only Suhrawardy who was subjected to indignities by Ayub Khan and his coteries; almost all politicians of that era became targets of insults; and that included the universally respected Fatima Jinnah who had the courage to challenge the dictator but was defeated by Ayub Khan with the might of his entire civil and military bureaucracy in the rigged presidential elections. Fatima Jinnah had won a landslide in East Pakistan, and Bengalis had hoped to see the revival of democracy with her win but Ayub stymied any such efforts.

The populism of Mujib was a direct corollary of General Ayub Khan’s attempts to stamp out any worthwhile opposition from Pakistan’s political landscape. As the 1960s ended, Mujib became increasingly exclusionist, targeting West Pakistan in general and Punjab in particular. His Bangla nationalism proved to be a hoax when in an independent Bangladesh, he concentrated all powers in his own hands and started cracking down on opposition almost in the same fashion as the generals from West Pakistan had done. His authoritarianism sealed his fate and left no doubts in the minds of political observers that he was indeed a populist.

In the independent India, perhaps the beginning of populist politics was in the 1950s when various nationalist leaders representing diverse ethnic groups demanded demarcation of administrative units (states) on linguistic basis. The Indian National Congress (INC), led by Jawaharlal Nehru, was sagacious enough to defuse this populism by accepting most of the demands by creating new units mostly on linguistic grounds.

However, in Maharashtra, the Shiv Sena brigade from the late 1960s onwards, introduced a new populism that was more fascist than nationalist. Again, the continuation of democracy scuttled that populism too.

The Janata Party of 1970s in India was more of a democratic party than a populist one since it did not target any group other than Indira Gandhi and her politics. Janata Party’s successor in the shape of the BJP was, and still is, a populist party as has become clear once again in the UP when it did not field a single Muslim candidate in a state which has almost 20 per cent Muslim population. Its exclusionary politics -- outright claiming that it considers everybody living in India as a Hindu -- has won it many elections throughout India.

An interesting aspect of populism is that it attracts voters even from those who are not in its list of beneficiaries. For example, in the Trump win in the US, many women and even blacks voted for him. Similarly, in the UP elections, there are constituencies where a candidate cannot win without the Muslim support but still BJP candidates have swept the polls. In the US, President Trump has so far appointed only one black at a cabinet post, making it clear where his preferences lie.

It seems the populists can create a positive perception thanks to their demagogy that appeals more to emotions than intellect.

In India, the BJP has been able to create that perception by targeting Pakistan externally and by promising a sea change internally. Sometimes these perceptions are so strong that they can defy reality. For example, in the US many economic and social indicators improved during the Obama administration but still the Trump campaign created the perception of ‘insecurity’ and ‘lack of greatness’ and promised a more secure and great America.

Similarly, in India the BJP and its extended family of Saffron Brigade constantly harp on the need of a more Hindu, more secure and greater India, making it difficult for their critics to challenge these slogans.

Talking about the recent UP elections, could we call the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) of Mayawati and the Samajwadi Party (SP) of the Yadavs populists? Well, to some extent yes (our Indian friends may disagree). But if we keep three important features of populism namely exclusionism, emotionalism, and economism, the BJP appears to be much more populist than any other party. The characteristics of populism vary from party to party and place to place but when they target the ‘other’ (exclusion), appeal to your sentiments rather than intellect (emotionalism), and promise quick economic success by drastic measures (economism), you can be sure you are dealing with populists and not democrats.

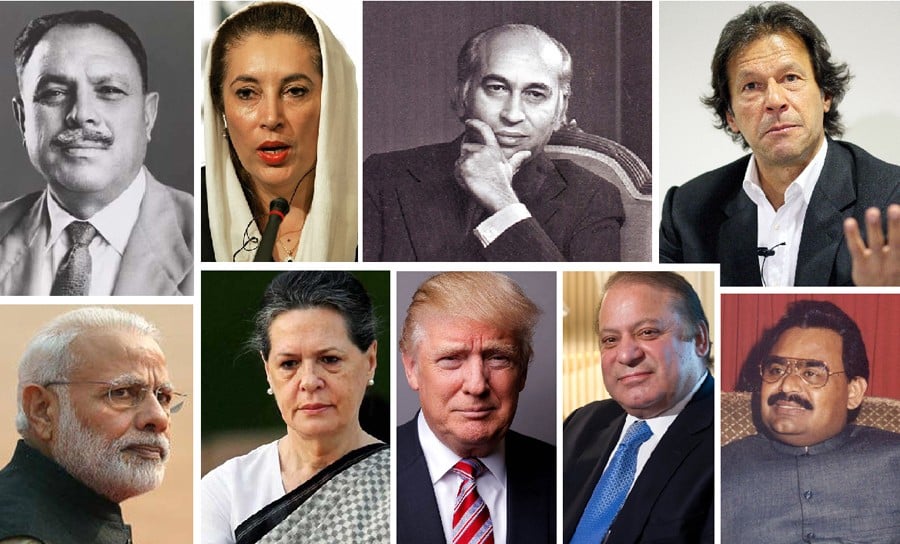

In Pakistan, after Mujib, we may call ZA Bhutto a populist leader in the sense that he did indulge in exclusionary politics by declaring that ‘Islam was the religion’ and ‘socialism was the economy’. His consensus development against the Ahmadis was exclusionary; his repeated tirades against India and promises to fight for a thousand years were emotional; his entire nationalisation programme was based on his promises for quick economic turnaround. Later in his career, his decisions to cater to religious sentiments were both exclusionary and emotional.

After Bhutto, General Zia continued to exploit popular sentiments but he was more of a fascist that a populist leader. He never had mass support -- just remember his referendum when most people abstained from voting. Another attribute of populism is that it relies on people’s support, at least initially, to grab the power.

Once the populist leader is in a position of authority, he tries to become an authoritarian leader. A dictator may not enjoy any popular support initially but then tries to play populist by following exclusionism and emotionalism, just as General Zia did throughout his 11-year rule.

Benazir Bhutto was popular but seldom played any populist games; she believed and acted for inclusion, appealed to your intellect rather than emotions -- well in most cases, and was careful not to indulge in economism. By economism we mean reducing all social problems to an economic one and projecting a couple of economic steps as a panacea e.g. CPEC in Pakistan, demonetisation in India, and the protectionism of Trump.

Altaf Hussain was more of a fascist than a populist leader albeit at a local level. He did politics of exclusion, appealed to emotions and projected quota system as the main cause of economic problems his supporters were facing. Altaf’s phony attempts to transform the MQM into a Muttahida or United movement failed because of his own miscalculations.

Nawaz Sharif does occasionally try to be a populist leader but overall the PML-N has some populist elements. Imran Khan for sure is a populist leader verging on fascism, though his party is less violent than the MQM used to be. Imran’s persistent refusal to criticise Taliban and continued support to outfits such as seminaries well known for nurturing the Taliban make him one of them. With Altaf Hussain, Imran Khan, and Tahirul Qadri, we have had more than we deserve of populist leaders.

Now the question: how can democracy defend itself against populism? Probably, by avoiding the features of populism. One, focus on inclusive politics. The recent statements and gestures from Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and the PPP leadership are a step in the right direction. The major political parties should work to withdraw all discriminatory laws against the minorities. Two, make attempts to appeal to people’s intellect rather than emotions; we need to do a lot in that direction. The narrative should not come from the mosque, pulpit, or the temple; it should come from the curriculum, journalism, laws, media, policies, statutes, and textbooks.

Finally, economism should be avoided by not projecting infrastructure as a panacea. CPEC, Metro bus, and green and orange lines are part of the solution and not the only solution. Extraordinary stress on CPEC and that too with a high level of secrecy is harmful. The best antidote to populism is adherence to democratic principles by inculcating a culture of democracy that should go much beyond electioneering and oath taking.