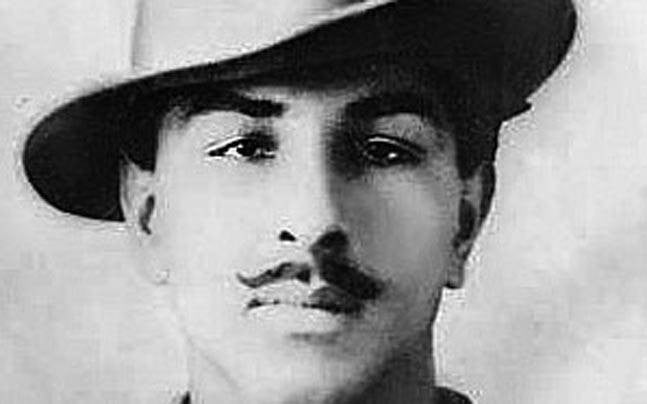

Some reflections on the legendary freedom fighter whose recognition is still widely contested

The people of Lahore routinely meet the Fawara Chowk, in the heart of Shadman, often without knowing the historical significance of the place. They don’t know that it was here that three legendary freedom fighters including Baghat Singh sacrificed their lives, in their struggle to free the people of the united India from British imperialism and exploitation of capitalists. Their slogans -- "Long live revolution!" and "Death to British imperialism!" -- seem to have been lost on the common Lahori, over the past 87 years, and in the din of everyday traffic at the juncture.

But there are those who gather around the Chowk every year on March 23, in memory of these freedom fighters, despite the threat from the hard-line, religious extremists who have variously attacked them and harmed them in the past.

The sad fact is that whereas the new generation seems to have little or no knowledge of Bhagat Singh, the older generation isn’t sure whether to call him a hero. Singh loved his land and its people, and did not like that lines should be drawn on the basis of religion. This is one major reason why followers of different religions have been reluctant to own him -- at least in public.

Different people have different things to say about Bhagat Singh, though no one contests the fact that the Lyallpur-born Sikh boy was a fearless freedom fighter, who embraced execution at a young age of 23 without budging.

According to Syed Muhammad Nisar Safdar, an intellectual and President of Bhagat Singh Lovers Association (BSLA), Singh was born in a politically conscious household that made him aware of what was happening in the world around him and how the locals were being exploited under the colonial rule. "His [Bhagat Singh’s] father was also a political agitator who was released from prison the day Bhagat was born."

Safdar says their family had immersed itself in the independence movement. "Following in his father’s footsteps, the young Singh joined Gandhi. As time passed, his ideology became influenced by the philosophy of socialism and communism. He alienated himself from Gandhi when the latter called an end to the non-cooperation movement, resulting in Hindu-Muslim riots. He understood that due to religious differences, Muslims and Hindus were ready to kill each other whereas they had begun the struggle together.

"This proved to be a turning point in his life. Bhagat shed his religious ideology and started reading Marx, Lenin, Trotsky and others revolutionaries. The socialist revolution became a goal and he devoted the rest of his life for the well-being of people regardless of their religion, colour and creed."

Safdar recalls that in 1926, Singh established a revolutionary group of left-wingers, known as Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS). Its objective was to set up an independent Republic of Workers and Peasants in India. "His ideology matured with the passage of time. He had merged his organisation with the Hindustan Socialist Republic Association (HSRA). His commitment towards the people and the revolution fascinated the youth of the then united India."

Leading historian, researcher and academic Yaqoob Bangash says Bhagat Singh was martyred at the time when the All India Muslim League was pro-British, "That is why he could not be recognised as a hero. Moreover, his ideology was not intelligible to most people. He came from a middle class family which proved to be another big hindrance in accepting him as a national icon. He didn’t belong to the upper class like Jinnah and Gandhi."

Bangash says Singh would be accepted as a hero in Pakistan if we followed the citizen-based country narrative. This narrative, he insists, is the need of the times and a solution to our problems such as terrorism and extremism.

"Today, India has accepted him [Bhagat Singh] because he was a Punjabi. We don’t have many icons in Punjab, and Pakistan has adopted heroes from other countries."

Farooq Tariq, Secretary General, Awami Workers Party (AWP), is of the view that Bhagat Singh and his revolutionary friend Batukeshwar Dutt exploded a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly, in New Delhi, in 1929. "Their purpose was not to hurt or kill anyone. Actually, Bhagat wanted to gain attention.

"Eventually, he was arrested by the British army. But Singh and his comrades used the platform of the trial court to spread their message. On January 21, 1930, they appeared before the court wearing red scarves. When the magistrate seated himself on the chair, they started chanting slogans like ‘Long Live the Socialist Revolution!’ and ‘Down with Imperialism!’

"Bhagat Singh, Raj Guru and Sukh Dev were brought to the gallows. Their crime was that they had raised their voice against the British imperialism. But they weren’t scared of death at all. Even at that time they kept shouting, ‘Inqalab Zindabad!’ Later, they were taken to the gallows which is now Fawara Chowk in Shadman, Lahore, where they were hanged till death."

More than eight decades since the tragedy, the government of Pakistan is still loath to accept Bhagat Singh as a national hero. It is afraid of the ‘consequences,’ so to speak -- a violent reaction from the fanatic religious factions.

But we must blame our history books that have rendered a freedom fighter like Bhagat Singh controversial. It is a pity that the villains are often the heroes, and vice versa, because we projected them as such, for our own vested interests. For their part, the religious sections say an atheist could never be the hero of a country that had been created in the name of religion.

A few years back, the City District Government Lahore (CDGL) announced that Shadman Fawara Chowk would be renamed as Bhagat Singh Chowk, in order to honour the brave young man of the land. After strong opposition from religious organisations like Jamat-ud-Dawa (JuD) and Jamat-e-Islami (JI), the project was put on hold for an indefinite period of time.