I held the pinna and tried to find my cousin’s kite in the sky and suddenly he started hooting and yelling, and so did the rest of our roof. Bo kata!

Two decades ago, I remember climbing up to the rooftop of my grandmother’s house on a stepladder. My mother shouting to be careful, my cousins beckoning me to climb quicker. There were a dozen kites lying in one corner -- white, blue, a yellow one with the black eyes of a butterfly.

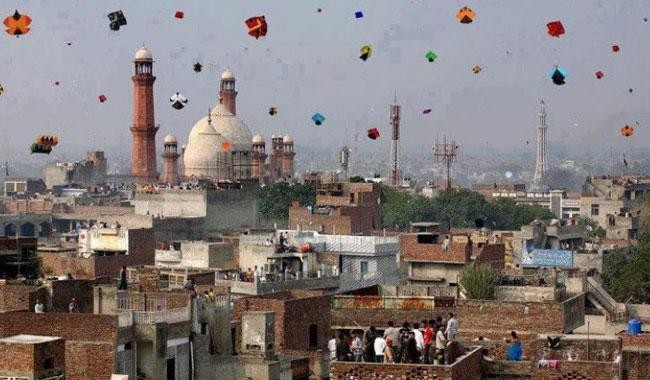

My grandmother lived in Samanabad, where the streets were narrow, the houses clustered, so the sky was full of movement and colour. I could hardly see the clouds.

"Hold this twine," one of my elder cousins said to me. I was young and still learning the ropes, or threads in this case. So I held the pinna and tried to find my cousin’s kite in the sky and suddenly he started hooting and yelling, and so did the rest of our roof, and I joined in without knowing what had happened. Bo kata! My cousin had felled another kite from the sky.

A decade ago, or 12 years to be exact, is the last Basant I remember. There were a couple of half-hearted ones in the years to come but bereft of the colour and fervour with which spring used to be welcomed in Lahore.

The Supreme Court banned Basant in 2005, because ‘it endangered the lives of citizens’. This year too, the Punjab government came out to categorically say that Basant will remain banned. Shahbaz Sharif took to Twitter to quash the rumour which started following the successful hosting of the PSL final. ‘If that can happen, why not this.’

The dangers, of course, are real. Children have fallen off rooftops unsecured by railings, while chasing the tail of a kite. Aerial firing after cutting down another kite has killed and injured people. Twines laced with shredded glass haven grievously injured motorcyclists in the streets below. I have personally experienced the sharp cut of a ‘chemical dor’ while bicycling my way home on a Basant.

But these are organisational problems. Again, ‘if 12,000 policemen can be called in to secure a cricket match, surely a thousand or so can make sure unsafe twine isn’t being sold, that aerial firing doesn’t take place, that motorcyclists wear helmets,’ and so on and so forth.

As always in Pakistan, however, there is a religious twist to the matter as well. The ban was supported by hard-line Islamist groups like Jamaat-e-Islami, who called it a Hindu festival encouraging devious activities like ‘loud music, dancing and drinking alcohol’.

Rana Sanaullah, comfortable with both the hard-line politicians and Islamists, called it a ‘throat-cutting festival.’ Maybe he’s forgotten the real throat-cutting festivals up north and the west(!) where the federal government says it is fighting extremists.

The Punjab government too, at long last, has decided to fight terrorism. Maybe that’s why police in Faisalabad arrested 209 people last month on charges of flying kites. Because what could be more terrifying?

Taking Basant away from Lahore isn’t just sucking more joy from this city or disrespecting a centuries old tradition. It has also left people without livelihoods. The All Pakistan Kite-Flying Association has appealed the ban on Basant several times, saying it has affected the primary income generating work of around 300,000 people.

I remember going to Shahdara for kite shopping year after year with my maternal uncle. The winding streets were full of vendors, both seasonal and year round. One had to decide how many and what size of guddi to buy; taawa, dedh taawa, chaar taawa, chhay taawa… How many twines, and how much medical tape to get. Both to wrap around fingers and heal injured kites with.

With exploding generators causing so much damage in this city, and hate speech being aired from television stations and minarets, it’s strange that an activity with a significantly lower death toll is the one so ferociously shut down.

If you can’t give us security, at least give our Basant back.