What has been the Movement’s impact on the practical meaning of the judiciary’s independence, its relationship with the lawyers and the latter’s own concept of their role in the dispensation of justice?

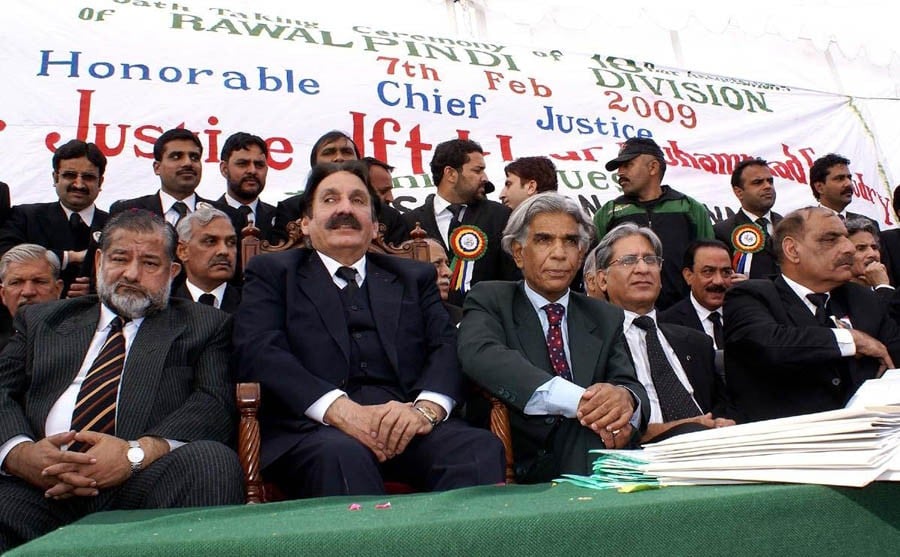

The Lawyers’ Movement -- March 9, 2007 – March 15, 2009 -- occupies a unique place in Pakistan’s history. Its success in getting Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry restored to his post twice, and also getting the superior courts’ judges, sidelined along with the CJ in Gen. Pervez Musharraf’s second assault on the judiciary, reinstalled is unreservedly acknowledged at home and abroad.

But what has been the Movement’s impact on the practical meaning of the judiciary’s independence, its relationship with the lawyers and the latter’s own concept of their role in the dispensation of justice?

To find answers to these questions, we may take a brief look at the objectives of the Movement. The lawyers were forced to respond to a sudden crisis caused by Gen. Pervez Musharraf’s bid to bully the chief justice into surrendering his august office. They had little time to think of anything beyond the immediate task of foiling the president’s intrigue. However, as the Movement took shape through the people’s participation, its leaders did evolve a set of objectives.

Perhaps the most coherent enunciation of these goals is found in Muneer A. Malik’s book, The Pakistan Lawyers’ Movement, that carries the eye-catching sub-title, "An unfinished agenda’. (Pakistan Law House, 2008). As President of the Supreme Court Bar Association in 2007, Muneer Malik not only organised the legal resistance to the presidential manoeuvre but also led countrywide agitation for the restoration of the judges until Ali Ahmed Kurd took over in the final lap to victory in the second phase of the struggle.

"The first element of our strategy," Muneer Malik says, "was to change beliefs that had enslaved the masses even after their liberation from the colonial rule… We wanted to educate the people that their fundamental rights and liberties could only be realised under an independent judiciary and we wished to explain what we meant by an independent judiciary." (Emphasis added). (This thought found an echo in Asma Jahangir’s Foreword to the book in the following words,… "the goal of the Movement is not only to restore the dignity of the courts and the judges that have been deposed but also to reinforce the dignity of Pakistanis.")

Read also: In view of the bar

The second objective of the Movement, according to Muneer A. Malik, "was to change the mindset of the judges…. We needed to inculcate in them the belief that… their true duty was to provide justice to the weaker sections of society irrespective of any pressures or constraints imposed by the ruling elites."

The third objective was to change the mindset of political leaders by persuading them to have faith in the people’s strength and also "to remind them that a free and democratic society rests on the edifice of an independent judiciary". "Finally," says Muneer Malik, "we wanted to change the mindset of the military, bureaucratic, feudal and capitalist establishment itself… they needed to learn that they could no longer continue to lord over the masses like a foreign occupying force." Brave words, indeed.

The question whether the Lawyers’ Movement made governance more democratic is not easy to answer. A great deal of evidence is available to suggest that while the parliament has learnt to pay some respect to democratic formalities, the executive has not shed the legacy of authoritarian rulers. But, at the moment, we are not taking up this issue for any further discussion.

The immediate result of the restoration of the chief justice and other judges was the chief justice’s assertion of the Supreme Court’s independence.

The first steps taken by the Supreme Court after March 15, 2009, included superior courts’ reorganisation. New judges were added to the Supreme Court bench. More than 100 judges of the Supreme Court and high courts who had taken oath under the PCO of 2007 were laid off and the Islamabad High Court abolished. The SC nullified a number of Gen. Musharraf’s ordinances and referred 37 of them to the parliament for ratification within 120 days.

Later on, the court struck down one of these ordinances, the National Reconciliation Ordinance, as invalid ab initio. The Supreme Judicial Council added a clause to its code of conduct for judges of superior courts that barred them from rendering any support, including the making of a fresh oath, to any authority that seized power through unconstitutional means.

More significantly, the Chaudhry court extended the frontiers of its independence through frequent exercise of its suo motu jurisdiction and its authority to punish for contempt. The human rights cell of the Supreme Court was energised, with the result it received thousands of petitions for relief. In several suo motu cases the government was obliged to rescind its orders/policies and through contempt proceedings the court was able to depose two prime ministers.

The court, however, soon went beyond asserting its independence of the executive to independence of the legislature, thus challenging the supremacy of the parliament. This was confirmed when the Supreme Court obliged the government to change the formula for the appointment of judges laid down vide the 18th Amendment and virtually extinguished the role of the parliamentary committee in the matter.

Thus, the position after the 19th Amendment was that the chief justice was in control of the judges’ selection process in addition to being the head of the Supreme Judicial Council and the Law and Justice Commission. This concentration of power in a single person apparently bypassed the dictum that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

This kind of activism could not for a variety of reasons be sustained and many were visibly relieved when Chief Justice Chaudhry’s successors wisely and graciously tampered the court’s activism with the cardinal principle of judicial restraint.

Nevertheless, the principle of judicial accountability suffered considerable erosion. The Supreme Judicial Council became dormant and this gave rise to complaints.

The full-blown judicial activism attracted criticism on several counts. Intervention in a large number of cases meant no authority, including the subordinate judiciary, was functioning properly. The apex court became the forum of the first resort, instead of being the final one. The cases against the government, in which the SC instead of issuing directions to the executive chose to replace it, made quite a few people feel that the court had been affected by the post-2008 election government’s dilly-dallying on the restoration of judges.

Read also: From justice to chief justice

The UN Rapporteur on Independence of Judiciary, too, was constrained to observe that the court was tending to impinge on the principle of separation of powers and that some of its work smacked of vengeance. Similarly, the court’s decision to deal itself with the PCO judges did not escape criticism.

The establishment tolerated judicial activism so long as the party at the receiving end was the executive, and to some extent the legislature. But it did not feel shy of drawing the line the SC could not cross. The court’s inability to do justice to the wretches, known as the Adiala Eleven or to get Munno Bheel’s family recovered showed the limits to judicial power.

The case of enforced disappearances was no different. The Chief Justice took his court to Quetta, rebuked the bureaucracy and threatened all and sundry with dire consequence but the establishment refused to yield. Even the report of the 2010 judicial commission was not made public, to say nothing about action on its recommendations.

Besides, when CJ Chaudhry rejected the parliament’s rights to move away from the theocratic model, he himself accepted an extra-constitutional bar to judiciary’s independence.

Unfortunately, in its pursuit of activism the superior judiciary allowed its understanding with the bar to be eroded and eventually the latter had to take exception to judges’ monopoly over their selection/appointment procedure.

While the rejuvenated judiciary did offer relief to ordinary citizens in a good number of cases, access to justice became harder, especially for the poor and victims of discrimination on the basis of belief. The dream of guaranteeing the under-privileged access to justice through institutional mechanisms remained largely unrealised.

Finally, the Lawyers’ Movement left an unhealthy effect on a section of lawyers themselves. Some of them started believing that, like the judges, they too had an authority to chastise members of the administration, including the police and subordinate judges. Clashes between lawyers and police and incidents of junior judges’ chambers being locked became common.

This part of the story may aptly be concluded on a report in last Thursday’s newspapers to the effect that lawyers had forced the LHC to shift courts from Bhowani to the district headquarters at Chiniot.