A personal account of the events taking place before the 1977 general elections, the rise of the ultra-right and the fall of leftist politics in Pakistan

A lot has been written and discussed about the coup General Zia staged in July 1977. Not much attention has been paid to the first three months of 1977 that paved the way for the coup to follow. As a teenager in the 1970s, one remembers the meetings and discussion among the left-wing activists and intellectuals who were initially not sure about who to support, but gradually tilted towards the right-wing Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) and then whole-heartedly supported the anti-Bhutto agitation.

In Sindh generally and in Karachi particularly, the leftist circles were divided in many groups led by comrades such as Jam Saqi, Dr Aizaz Nazeer, Jamal Naqvi, Ali Amjad, M R Hissan, Barrister Abdul Wadud, Fasihuddin Salar, Anis Hashmi, Sobhogayan Chandani, Muhammad Mian, and many others. My father, an old leftist from his younger days in Bombay, owned a small picture-framing shop in Liaquatabad (Lalukhet) Karachi, but we lived in Malir. My memories of the early days of 1977 consist of the heated discussions my father had with his comrades on the issue of whether to support Bhutto or not.

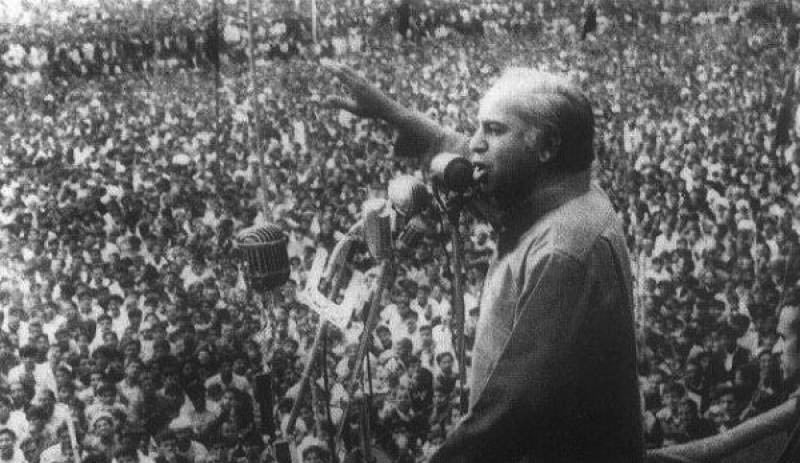

But first some background. Z.A. Bhutto had contested the elections in 1970 with the slogans of democracy and Islamic socialism -- whatever that meant to him, but for the people he had a charisma. After coming to power in post-bellum rump Pakistan, he launched a massive nationalisation programme taking over major industries, educational institutions and financial sectors. His early comrades included people such as J.A. Rahim, Meraj M. Khan, Mubashir Hasan, and Sheikh Rashid but as Bhutto entrenched his feet with power, his sympathies shifted to the feudal class.

From 1972 to 77, Bhutto persecuted left-wingers not only in his own party but also targeted the only national-level political force with left leanings i.e. the National Awami Party (NAP) led by Abdul Wali Khan. The dismissal of the NAP-led provincial government in Balochistan and then the resultant resignation of the JUI-NAP coalition in the NWFP (now KP) did more harm to democracy in Pakistan than any left-wingers could have done.

So, when the general elections were announced by Bhutto in January 1977 to be held in March, the left-wingers were almost unanimous in opposing Bhutto. My father was not a fan of Bhutto but when the PNA was announced, he simply refused to side with the mullahs.

The comrades who used to visit my father at our home and shop, both openly and in disguise, didn’t like his reluctance to support the PNA. He had played an active role in campaigning for Mahmudul Haq Usmani, a NAP candidate in the 1970 elections. Now the National Democratic Party (NDP) -- the successor of NAP -- led by Sardar Sher Baz Khan Mazari was part of the PNA and our comrades, aligned with the NDP, were toeing the party line and expected my father to follow suit.

To the comrades, Bhutto had proved himself to be a fascist and the continuation of his government would mean further disaster for the country and for the left politics in general. To my father, Bhutto was a populist leader in love with himself who could jump on any opportunity to remain in power and go to any extent to crush his opponents; but he was not a mullah, and that was good enough. Despite his authoritarian streaks, Bhutto to my father presented a brighter side of Pakistan as opposed to the far-right religiosity of the PNA.

I remember, for the first time, my father was declared a CIA agent, a traitor to the proletarian cause, a petty-bourgeois shop-owner who had changed his class character and was betraying the revolutionary cause. I still wonder how the CIA penetrated the streets of Karachi to recruit my father! Perhaps it had permeated there not on my father’s side but, as the post-election riots showed, against Bhutto.

Our comrades were put off. My father declared his desire to work for the PPP and joined my uncle -- a diehard Bhutto fan -- who had opened a corner office in his two-room house to run the election campaign of Abdul Hafeez Pirzada, contesting for a National Assembly seat from Malir.

The announcement for elections was made in the first week of January 1977. The opposition was in disarray that Bhutto wanted to capitalise on. Surprisingly, within days, the opposition parties of different hues joined hands and an alliance came into being called the PNA. It contained nine parties as diverse as Jamaat-e-Islami, JUI, JUP, PDP, Tehrik-e-Istiqlal, and the NDP. Those who would not otherwise offer prayers on the same mat were now friends in need of each other. Maulana Mufti Mehmood, Maulana Maududi, Maulana Shah Ahmed Noorani, Maulana Ghulam Ghous Hazarvi -- in short, maulanas of all shades were united.

The odd ones in the PNA were the non-maulanas like Asghar Khan, Nasrullah Khan, Sher Baz Mazari, and Comrade Yousuf Masti Khan who had lined up behind the slogan of Nizam-i- Mustafa, just to get rid of Bhutto. Suddenly, Karachi witnessed a shameful smear campaign against Bhutto and his family. As a school-going teenager, I remember the magazine photos of women in bikinis with faces of Bhutto and his wife glued on them and pasted on walls and hanging from electric poles. The PNA workers in Karachi were mostly from JI and JUP who felt no remorse in maligning the women of the Bhutto family.

In corner meetings, that I happened to witness from close quarters, mainly in Liaquatabad and in Malir, most of the hirsute speakers targeted Bhutto as a non-Muslim declaring that he was the son of a Hindu mother. I used to discuss these accusations with my father who would laugh it off by recalling similar accusations he had heard in Bombay when even leaders such as Jinnah and Azad were not spared and their integrity and loyalty to Muslims were questioned. Another favourite target was Bhutto’s taste for tipple; my father himself never drank but didn’t mind others doing it. He would tell me that religious intoxication was much worse than any other.

The slogans used became personal and were in bad taste, for example Ganjey ke sar pey hal chalega, (the plough will dig the crown of the bald one i.e. Bhutto), and Ganja sar ke bal chalega (the bald one will spin on his head). Bhutto himself had started mocking his opponents. He made fun of their names saying all names ended in ‘i’ such as Mufti, Maududi, Hazarvi, Mazari, and Noorani, making them feminine. He said only Asghar was different so he would call him Asghari.

Bhutto had also gone a bit too far by getting his opponents physically abused. A case in point was JI candidate, if I remember correctly from Larkana, Maulana Jan Muhammad Abbasi who was physically manhandled by PPP goons with or without orders from Bhutto. The entire state machinery was being blatantly used by Bhutto and his coteries. Bhutto’s choice of candidates in 1977 was diametrically opposed to what he had in 1970.

His preferences had shifted from a middleclass and educated lot to upper-class feudal lords or barely literate land owners. For example, from Malir the MPA candidate was Abdul Qayyum Jokhio who had no clue about politics, or anything else for that matter. As the elections approached in March ’77, the campaigns reached a crescendo with miles-long processions and rallies from both sides. If PNA leaders were on roads addressing their supporters for 10 hours, Bhutto would do it for 20 hours.

Having said all this, it was clear that Bhutto would win the elections, albeit with a lesser majority.

The Election Day on March 7 was hectic, the night even more so. In our two-room dwelling, one room was full of people watching tv till the next morning. There was jubilation on our side but gloom on the other. The PPP had won with a landslide of 155 seats out of 200, not awaited by our own workers. The PNA had won only 36 seats much lesser than anybody expected. The very next day, the PNA leadership refused to accept the results, blaming it on rigging and huge electoral fraud. They also announced the boycott of the provincial assembly elections to be held on March 10.

Initially there was calm, the March 10 election went ahead with no participation from the PNA. By the third week of March, it was all out war against the Bhutto government. Demonstrations had engulfed Karachi and then spread all over the country. The PNA workers became increasingly violent and the government reaction was in equal measure, if not worse. In Liaquatabad one of my distant uncle’s shop was named Peoples Glass House; a PNA mob burned it and my uncle ran for his life. His neighbour whose name was Allah Banda was an active member of the PPP. His woodwork shop was burned and he was lynched.

Our shop remained closed for many days because there was around 20 kilometres distance from home to work and public transport was hardly plying. It was becoming difficult to survive on meagre savings. After many days, we went from Malir to Liaquatabad but could not open the shop; on our way back we had to walk for more than ten kilometres, etched in the memory are burned houses, shops, buildings, banks, vehicles and a complete look of destruction in Karachi. At night, the PNA workers started saying azans from rooftops, it was as if a natural calamity was upon us.

Then the rumour came that our home was to be attacked for we were PPP supporters living amidst PNA followers. I remember my father and his friends gathering knives and metal rods to defend ourselves against any possible attack. Luckily, Malir was different from Liaquatabad which was mostly PNA dominated Urdu-speaking so-called mohajir population; whereas Malir had a lot of Sindhi and Kutchhi population that was pro-PPP. For many nights, we and our Sindhi friends kept a vigil to protect us and we were spared. My school year was ending and for two months there had not been any classes.

Then, the Sindh government announced that all school pupils would be promoted to the next grade without exams. I was in grade eight and got promoted to the ninth without any assessment. That was the only time in my educational career that I was promoted without an exam.

As March ’77 ended, it became clear that ultra-right would benefit, and it did. The biggest losers were the leftist, secularists, socialist, and communists who, still by the end of March 77, expected something positive to come out if Bhutto was replaced. What happened in the next three months deserves another article that will appear on the 40th anniversary of the coup in July.