An important book by one of the pioneers of Urdu broadcasting, Agha Ashraf, has been republished after 72 years

He truly was a man of letters who wrote thought-provoking essays, captivating radio columns and highly interesting travelogues. His name was Agha Ashraf, and he was one of the pioneers of Urdu broadcasting in India and England.

Like many carefree artistes, he never kept a record of his achievements, with the result that his articles and speeches are scattered in old magazines and radio archives. Some of his war dispatches and essays were published in a book 72 years ago, but that publication had long been extinct.

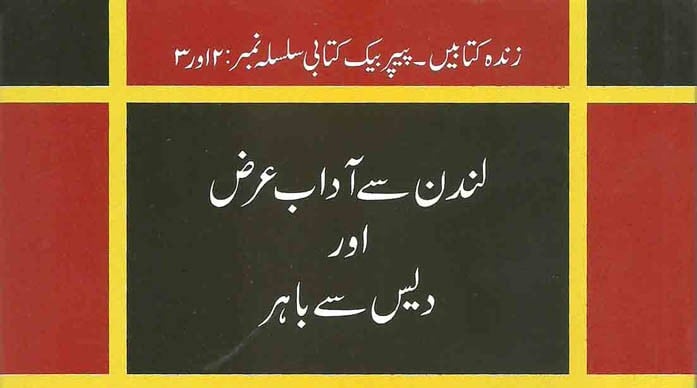

Bazm-e-Takhteeq-e-Adab took up the task of publishing those dispatches and articles again, and the result is this beautiful collection called London se Adaab Arz (Greetings from London).

From 1939 to 1943, Ashraf worked in London as the chief announcer and programme director of the Hindustani Service of BBC. These were the most crucial years of the Second World War, as Hitler was invading his neighbouring countries one after another and London was under constant attacks from German bombers.

Ashraf was placed centre stage in the theatre of war and a witness to the notorious London Blitz, the strategic bombing campaign against London and other English cities, which began on September 7, 1940 and continued for 57 consecutive nights. Breaking all rules of the game, the Germans bombed the densely populated civilian areas.

On September 11, 1940, Ashraf wrote in his dispatch: "Night attacks are now a daily routine. As soon as the sun sets, the German bombers and fighters appear in the sky. In the early days of war, were very curious to watch them and despite the air raid sirens, people would come out on the streets or open their windows to watch the German aircraft, but now they have developed an awareness about the great danger involved in it, and as soon as the sirens are activated, people run to the bomb-shelters and even a bustling place like Oxford Street becomes deserted in seconds. However, the moment an "all clear" siren echoes in the air, thousands of people surface from all nooks and corners of the city and cram into shops, restaurants, and public buses.

"The famous London Underground, at that time, is crowded like a Third Class compartment of the Indian Railways … There are many public shelters in town and when evening falls, I can see men, women and children, running towards these shelters, with their sleeping bags, pillows and bed-sheets.

"The house I live in, has its own small basement that can accommodate 4 or 5 people, but every evening eight or nine women with many small children come from somewhere and occupy the basement. I had never been to the basement and stayed in my room during the air attacks, but last night the German bombing was so ferocious that the walls of my room shook badly and the window panes cracked. I ran to the basement but could not stay in that overcrowded room for long and came back half asleep. I could see the red flames in the sky and my ears were torn by the loud blasts, but I didn’t care … and went to sleep."

The book, however, is not merely a war diary -- it depicts many political and cultural aspects of life in London, as it was in the early 1940s. Ashraf was present at the British parliament as a BBC correspondent when Churchill delivered his famous speech of July 2, 1942. He also attended the funeral of Lord Willingdon, the Viceroy of India till 1936. Ashraf had met Lord Willingdon in India and provides an interesting description of that meeting.

One article in the book is about the state of Urdu language in Britain, another is about Indian students studying at Cambridge. The author also met the famous Orientalist and linguist Dr Grahame Bailey and convinced him to write some speeches in Urdu, to be broadcast from the BBC. "Dr Bailey spoke excellent Urdu, and he was equally fluent in Punjabi," writes Ashraf. "He had spent many years in Punjab as a school teacher, and had managed to learn several Indian languages. In my opinion, after Dr Gilchrist of Fort William College, Dr Bailey was the greatest patron of Indian languages."

In another article, the author admits that nobody can match the linguistic talent and hard work of George Abraham Grierson who spent 34 years of his life (1894-1928) in the study of Indian languages and compiled his findings in the 19 volumes of Linguistic Survey of India. He travelled from town to town and village to village for gathering first-hand information on this vast subject; in total he surveyed 364 languages and dialects from the Indian subcontinent. He also made gramophone recordings of various dialects from the region, which are preserved in the British Library archives.

The last part of Ashraf’s book comprises his travelogues of Iran and Sri Lanka. The end of the book has two sketches of his personality: one by famous Urdu scholar Aslam Farrukhi and the other by Agha Muhammad Baqir, the author’s brother. In the second sketch one observes how this talented grandson of Maulana Muhammad Hussain Azad became an accomplished scholar of Persian and Urdu, and started teaching at the university level while he was only in his mid-20s. He married an English woman and had two daughters.

Ashraf lived a neat and clean life: abstaining from smoking, drinking and even meat. Sadly, despite all these preventions, he developed stomach cancer, and met an untimely death in 1962, at the age of 50.

Many of his articles are still scattered across various magazines and pamphlets, and some nuggets of his golden voice are said to be buried deep in the BBC’s audio archives. The ardent fans of Agha Ashraf expect a London-based researcher like Raza Ali Abidi to dig up the leftover archives and reveal the treasure they hold within.