Some extraordinary films have been produced across the world about politically motivated enforced disappearances

Whether you call it a simple ‘disappearance’ or a ‘politically motivated’ one, it creates terror in society not only for the immediate family but also for the entire thinking community that feels associated with the victim. This is a tool of oppression employed by state agencies and non-state actors alike who want to disseminate the seeds of dread in society at large.

The documentation of such disappearances is important so that society becomes aware of the excesses committed in the name of various ideologies and denominations that thrive in an atmosphere of fear.

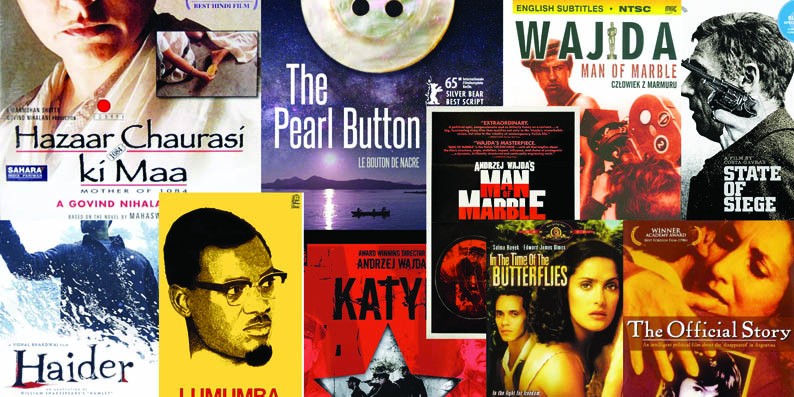

Directors have done a marvellous job by producing some extraordinary films that document such disappearances from Argentina and Chile to India and Indonesia. These disappearances vary in nature and magnitude, from a single ‘disappeared’ person to thousands who vanished with or without a trace. During the past hundred years or so, perhaps the first major case of mass disappearances occurred in Poland at the outset of the Second World War. The Polish director, Andrej Wajda, who himself had suffered at the hands of the communist regime in Poland, finally managed to document the entire episode of Katyn massacre in one of his masterpieces by the same name -- Katyn (2007).

Katyn is not a film; it is a tragedy on celluloid. Tragedy of a generation that was torn apart when a great number of Polish soldiers ‘disappear’ at the hands of the Soviet troops. The film tries to unravel the complicated circumstances Poland found itself in -- both in the war and after. The story telling in Katyn is done mostly by women related to the disappeared who are prisoners of the Soviet army that refuses to divulge any information about their location or condition. For the families, they have vanished in thin air.

After their capture in September 1939, the disappeared soldiers are executed on Stalin’s orders in 1940 but their families are not informed; neither are they sure whether their loved ones are dead or alive. The story is revealed when a young Polish captain’s diary is uncovered detailing the events that befell on the soldiers after their enforced disappearance. The Soviet army separates the officers from the enlisted men, officers are held and later killed. The diary records the names of officers with the dates they are taken. The film moves to the post-WWII period showing wives and daughters still waiting for their men.

Gradually the news of the Katyn massacre becomes known, including the names of the victims, but People’s Army of Poland, supported by the Soviets, blames it on Nazi Germany. The communist authorities -- both in Poland and the USSR -- carefully conceal the evidence but a few daring people do challenge the official version. The film’s last 30 minutes are horrifying with a reenactment of parts of the massacre. The film is not for the faint-hearted but if you want to watch a movie about how thousands of people disappear, watch this.

After the war, Poland comes under Soviet domination with a puppet socialist government that feels no hesitation in ‘disappearing’ people if they don’t fall in with the official line. Man of Marble (1977) is a film that tries to trace one such person, Birkut, who used to be a ‘hero’ of the Polish communist government in the 1950s but then suddenly disappeared from the public scene. Man of Marble attacks government corruption in a Citizen Cane-style story in which a personal history is being traced; in Citizen Cane, that is done by a journalist, whereas Man of Marble uses a film student to build the story of a long-forgotten public figure.

The story begins with a marble statue of Birkut, dumped in a museum basement. The student explores the archived propaganda films that once projected Birkut as an embodiment of the working class labour. The devout worker lays bricks like a slave and is rewarded for his Herculean efforts; but, when he starts expressing his concerns at the mistreatment of workers by the state apparatchiks, first he is reprimanded, and then suddenly disappears, never to be found again.

The student finally manages to trace his wife and son but not the man himself.

If the Nazis and the Stalinists could use enforced disappearances, the capitalist and imperialist powers were capable of even more heinous crimes. Entering the 1960s, we find numerous such disappearances of political leaders, activists, and even purported aid workers. Perhaps, the most shocking disappearance was of the Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, who was abducted, killed, and his body dismembered and dissolved in acid because of a conspiracy hatched by the American diplomats, Belgian soldiers, and Congolese rebels. These horrific events are documented by the Haitian director, Raoul Peck, in his French language feature film, Lumumba (2000).

The film portrays the last years of Patrice Lumumba -- the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo who championed national unity and overall African independence in the 1950s. The director selected the African-French actor, Eriq Ebouaney, who was in his mid-30s and looked exactly like Lumumba. The film begins by showing Lumumba’s civic organising skills and his involvement with the Congolese National Movement. His struggle leads to the country’s independence, followed by massive unrest and other leaders’ uprising stoked by the Americans and Belgians who had stakes in natural resources there, and feared that Lumumba would attempt nationalisation on the lines followed by Nasser in Egypt and Mossadegh in Iran.

Lumumba reenacts the events leading to his election as prime minister, his fiery speech on the Independence Day against the Belgian colonisers, and his removal from office and finally disappearance. He was prime minster just for seven months from June 1960 to January 1961 when he was abducted. For over a month, his whereabouts were not known and he was held incommunicado before his murder became known in February 1961. He was just 35 at the time of his elimination that paved the way for over half a century of pillage and plunder by military dictators in collusion with the western powers.

From Europe and Africa, we move to Latin America that was another battleground of competing ideologies. One may start with the film In the Time of the Butterflies (2001) focusing on the disappearance and murder of three beautiful sisters who dared to challenge the dictatorship of General Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic. Trujillo had seized power in a military revolt in 1930 and ruled with an iron fist for over three decades before being killed in May 1961. The film uses Mirabal Sisters and their father as the focus of the story. First, the father disappears, for his daughter -- played by Salma Hayek -- refuses the advances of the dictator himself.

The daughters become increasingly politicised against the military oppression and galvanise the Dominican youth only to be stalked, abducted and killed by the security forces that ruthlessly suppress any opposition.

The three Mirabal Sisters were killed in November 1960 but the fourth sister survived till 2014. In the Time of the Butterflies is a tale of bravery and compassion so wrongly associated with men but often better displayed by women across the globe. Salma Hayek who had given a compelling performance in Midaq Alley (1995) -- based on Naguib Mahfouz novel -- repeats her exuberance as Minerva Marabal aka butterfly.

Interestingly, such disappearances and killings were not only done by state agencies, but also by non-state actors. One such non-state actor was Tupamaros -- a left-wing urban guerrilla group in Uruguay in the 1960s and 70s. State of Siege (1972) directed by Costa-Gavras is a testimony of the history of Latin America of that period. President Pacheco tries to suppress labour unrest using a state of emergency and repealing all constitutional safeguards. The film revolves around Tupamaro movement that, in retaliation, engages in political kidnappings and assassinations. One such target was Dan Mitrioni, an FBI agent disguised as an aid worker.

State of Siege reveals that the kidnapped aid worker was advising the Uruguayan police in torture and other ‘security’ work. Dan Mitrioni was abducted in July 1970 and executed in August that year; the film recreates the entire episode with pinpoint accuracy, but with changed names. The kidnapping and interrogation shown in the film depict the big picture not only of Uruguay but also of other Latin American countries. It unpicks the shenanigans of American advisors in supporting military dictatorships. It deserves a mention that the film was made in Chile during the Allende presidency, shortly before the coup that overthrew Allende himself.

And that brings us to Chile, the focus of another Gavras film, Missing (1982) starring Jack Lemmon. But here one is more inclined to talk about The Pearl Button (2015) directed by Patricio Guzman who also wrote and directed Salvador Allende (2004). Guzman specialises in political movies without attempting to affect the audience sentimentality. In The Pearl Button, he begins with South American natives who disappeared with their lost word. The disappearance of that magnificent and unique world due to the arrogance of modernity covers almost half of the movie and tells the audience that the disappeared natives were not mindless savages.

Then the movie brings us to the industrial age and capitalism and the absurdity of the brutal crimes of the General Pinochet regime in Chile who usurped power after overthrowing the democratically elected Allende in 1973. The Pearl Button provides an intimate account of how the search for the ‘disappeared’ during the military government leads to the horrific details of tying up bodies with railroad shafts and thrown into the sea from military aircraft. Estimates put the number of the ‘disappeared’ from 12,000 to 14,000 bodies that were disposed into waters. Much later, during reclamation efforts, one of the bodies recovered had a pearl button attached.

The first film from Argentina to receive an Academy Award -- The Official Story (1985) -- details the disappearances of the thousands of Argentines during the Dirty War launched by the military dictatorship against its own people in 1976; one year before General Zia became a dictator in Pakistan.

To conclude, we may also mention two Indian movies -- Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa (1998) directed by Govind Nihalani and Haider (2014) by Vishal Bhardwaj. These movies show how countries such as India and Pakistan also indulge in enforced disappearances. We still have to see a single movie about such disappearances in Pakistan.