Witnessing tales of misadventure, death and desperation at the Lowari Pass

As I stand alone beside the road, I can see preposterous lines of vehicles stuck in a tunnel. An awful mixture of rain and sleet dribbles down from overhead clouds while the blaring of car horns and shouting of disgruntled travellers fills the air. A pungent smell of burnt diesel makes it difficult to breathe. This is why Raoli seems to be so irritating now.

Raoli, in the Khowar language of Chitral, refers to the Lowari pass between Chitral and Dir districts of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Perched here beside the road for over three hours now, I get a good opportunity for a visual inspection of the surroundings. The stream flowing near the mountain gulley to my left is hidden by a fifteen feet high glacier. Blue pines dotting the rapid rise of the hillside are majestically draped in a shade of white that is too fantastic to be real. The rock escarpments of the higher ridges in the distance are a dirty black, bereft of snow but thoroughly drenched by the moisture in the clouds.

It is this surreal moment that makes me wonder about the vicissitudes of Raoli. Through time, what all have these elements of nature been witness to?

The misery of the people I can see here has always been a trademark of Raoli, or the Lowari pass. At ten thousand and two hundred feet above sea level, Lowari is the lowest pass that gives the people of the Hindu Kush a passage to the subcontinent without requiring detour through an alien country. For this reason, Lowari has been an intimate part of the life or rather a lifeline for the Chitrali people since times immemorial.

For most of us, the name Lowari signifies a difficult high altitude mountain road notorious for its hairpin bends. For the greater majority of the people of Chitral though, it has been providing the only access to quality education, proper medical care and fresh eatables for sustenance. These positive attributes notwithstanding, Lowari has also inflicted pains ranging from desperation to death on the same people for which it is a source of life.

It is for this reason that Lowari is the bearer of countless stories of loss, hope, heroism and even treachery.

With such qualities, would not Lowari in the medieval ages have qualified the textbook definition of the word ‘deity’?

Let us all now rewind our clocks back to the freezing and dreary evening of December 19, 1905: A party of six men is straggling on the road from Dir to Chitral in incessant snowfall. Still five miles to go to reach the top of the Lowari pass; the lead in the party, Captain Robert Walter Edmund Knollys realising the lateness of the hour decides to call it a day in a Levy checkpoint less than half a mile ahead. The party slowly drags on towards the checkpoint in snow, no less than seven feet deep in some spots.

It is here then that an unmistakable thunder echoes in the hills towards the right of the party’s trajectory and, in the shortest time, immense magnitudes of snow rush down the slopes. Soon the whole view whitens out, and a fierce wind blows snow dust in all directions. As this snow dust settles and the roar of the thunder dies out, it is established that there has been an avalanche. As for the travelling party, the four men including Captain Knollys, the Assistant Political Agent of Chitral, get trapped in it.

Captain Knollys’ Chitrali orderly and a Dir villager going by the name of Ali walking some distance ahead and thus able to survive the avalanche, immediately rush back to the site and through persistent digging with their bare hands manage to save Captain Knollys. The Captain himself then immediately rolls up his sleeves and along with his two rescuers goes looking for the three other men buried completely in the snow due to the avalanche. Our three heroes manage to rescue all the trapped men using just their bare hands in an area notorious for avalanches -- one where secondary avalanches are known to follow the first ones.

For their gallantry, the trio -- an Englishman, a Chitrali and a Dir villager -- gets awarded the Albert Medal of the Second Class. Would this have been if it were not for a bleak but lucky evening on the Lowari pass?

I say ‘lucky’ because Captain Robert Knollys and his party cheated death that day. Rewind the clock just one more day and you will find that 22 men and 11 ponies did not survive avalanches on the same Lowari. In the thirteen months preceding this incident, the Lowari pass claimed a total of 36 human lives and that of 15 ponies in similar avalanche accidents. This had been the usual winter’s tale for Lowari.

Take the clock back to 1895 and you will find that Umra Khan of Jandul crossed the Lowari pass in the dead of winter under strenuous conditions with a force of 2,700 men apparently with the intention of waging a holy war against the Kafirs of the Hindu Kush (the Kalash people). In actuality, however, he was invited by the Mehtar of Chitral, himself a young lad who had just acceded to the throne by a treacherous murder of his own half-brother.

This crossing of Umra Khan with such a large force had rendered the Mehtar of Chitral’s own sovereignty vulnerable. He was subsequently told by the Mehtar to leave Chitral, a piece of advice Umra Khan disregarded. What ensued then was a forty-seven day siege of Chitral Fort with Chitral’s royalty and a British garrison locked in, and which was only lifted once the news of arrival of British reinforcements from Gilgit via the Shandur pass forced Umra Khan to turn back. This is the treachery to which Lowari has been witness.

Moving forward to October 12, 1954, a Royal Pakistan Air Force pilot and the Mehtar of Chitral perished in a plane crash in the Lowari Mountains. A mere ten years later, in the month of March in 1965 an aircraft of the Pakistan International Airlines ferrying passengers from Peshawar to Chitral crashed at Lowari, claiming a total of 22 lives. The Lowari has been a reckless killer, rather more of a devouring beast than a simple high altitude mountain road into uncharted territories. It is no wonder thus that air travel to Chitral or away from it has not been safe either.

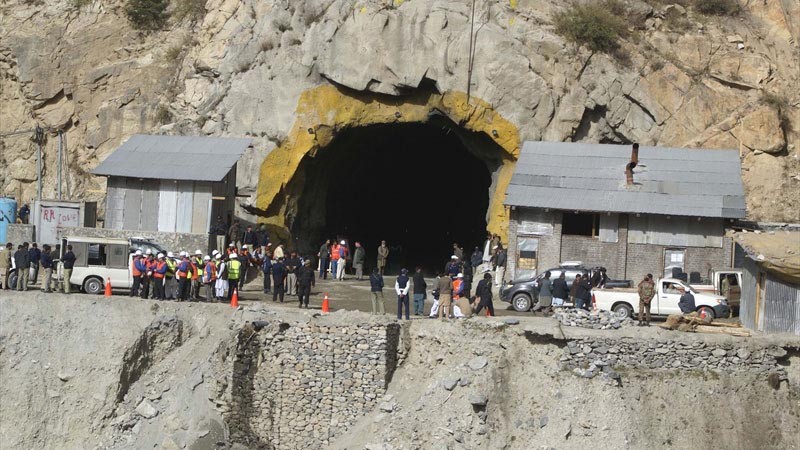

We now return to the present, where I am perched astride the road for over three hours now. I take a glance north to sneak a peek at the top of the Lowari pass. It is so far away that I cannot discern it from here. It is high too, and I am already below 7,000 feet above sea level. With ankle-deep snow all around me and fresh snow falling continually, I know that the long line of vehicles I see will only cross the Lowari pass with great difficulty. The vehicles are waiting for permission to pass through the under-construction Lowari tunnel. Thoroughfare through the tunnel is now allowed on certain days in the winters when the pass has been blocked.

In a while the car I was initially on manages to move past the bottleneck and catches up. Given the constant honking by the other stranded vehicles, I must board and move on. But standing here, and with a parting glance of the chain of mountains up and down the whole valley, I cannot but think that soon after the completion of the Lowari tunnel, the historic road through the pass shall be abandoned leaving many future travellers wondering what exactly Chitral’s Raoli problem had been.