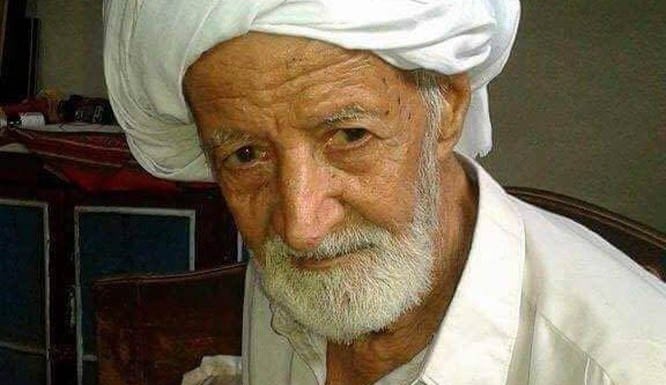

A source of inspiration for poets, Saeen Ahmad Khan Tariq delicately weaved a tapestry of resistance for which he deserves glowing tributes

On February 10, legendary Seraiki poet, Saeen Ahmad Khan Tariq, passed away after a protracted illness. With his death, an era of Seraiki poetry has come to an end. He was 92. He left behind a widow, two sons, eight daughters, eight books and hundreds of fans and followers.

Saeen Ahmad Khan Tariq is counted among contemporary classics of Seraiki poetry like Noor Muhammad Saail (late), Jaanbaaz Jatoi (late), Sarwar Karblai (late) and Iqbal Sokri.

Tariq was born and bred in Shah Sadar Deen, a small, dusty town on Indus Highway, some three kilometres west of Indus River and 27 kilometres towards north of Dera Ghazi Khan.

He opened his eyes in an idyllic landscape of the floodplains, locally called Bbaytt. His poetry is marked with his fondness of Bbaytt. The soil and water, the birds and animals, the ferrymen and fisher-folks, the peasants and pastoralists, and all the ordinariness of Bbaytt inspired and enriched his poetic imagination, themes and symbolism.

Kijjrray Kaalay Kolay Laggdoon

Parriyay Cheeray Cholay Laggdoon

Wull Wull Saaddo Kiyun Paiay Ddayhdo

Bbaytt Day Loke Hain, Bholay Laggdoon

[(We, who) appear to be soiled and as black as coal

The culture of Mushaira (poetry recital sessions) has been quite strong in Dmaan -- the area bounded by Suleman Range in the west and Indus River in the east, comprising Tank, Dera Ismail Khan (in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), Dera Ghazi Khan and Rajanpur (in Punjab) districts. In his early youth, Saeen Tariq started frequenting Mushairas organised in nearby towns.

His affection for Mushairas grew so intense that he would cover long distances on his bicycle to participate in those arranged as far as in Taunsa Sharif, Pull Qambar, Shahdan Lund and DG Khan. Slowly, he started composing poetry.

However, before being acknowledged as a poet, the tradition required him to have an Ustaad (tutor), who should provide him guidance in rhyme and meter as well as Islaah (correction) of his verses. Going by the tradition, Tariq offered Shakar (brown-sugar) to Noor Muhammad Saail, a poet of his own stature, who accepted it, implying that the latter agreed to take the former under his tutelage.

The kind of poetry that was in vogue at that time was immersed in folk and oral tradition. It had more to do with performance (e.g. recital or singing) than reading. Skilful usage of homonyms, homophones and homographs were some tested devices on the part of poets to hook the audience and win their applause. Ahmad Khan Tariq was master of these poetic devices, the manifestation of which can be seen in his following Ddohrra (a four-liner genre of poetry).

Ddukh Ddukh Honday, Ddukh Koi Howay, Naan Ddukh Da Chauoon, Bahoon Ddukh Laggday

Ddukh Hik Taan Naieen, Ddukh Kaafi Hin, Ddukh Gginn Sunnwauoon, Bahoon Ddukh Laggday

Ddukh Chhayrroon Taan Ddukh Chhirr Possen, Ddukh Haan Koon Laauoon, Bahoon Ddukh Laggday

Ddukh Bbaitthen Tariq Ghund Keeti, Jay Ghund Khulwauoon, Bahoon Ddukh Laggday

[Pain is pain, whatsoever pain is, (if we) name the pain, it pains a lot

Though he composed poetry in different genres, including Ggaawann, Kaafi, Nazm, Ghazal, etc., his Ddohrras earned him immense popularity. Besides love (e.g. longing for beloved or separation from beloved), the issues of common man/woman (mostly expressed in feminine voice) are dominant themes of his Ddohrras. His following Ddohrra narrates a sense of deprivation felt by basket-weaving landless community.

Na Malik Milkh Zameen Day Hain, Na Maal Ay, Tokray Bbadhnnay Hain

Assaan Kaambaan Taann Kay Bbahnday Hain, Jhar Jjaal Ay, Tokray Bbadhnnay Hain

Eehaa Ggalh Hamesha Kiyun Puchhdain, Taikoon Haal Ay, Tokray Bbadhnnay Hain

Saadda Tariq Dil Hay Jug Waanggoon, Eehaa Ggalh Ay, Tokray Bbadhnnay Hain

[Neither the owners of land nor the holders of animals, we are basket-weavers

His poetry is not overtly political. He questions the issues of oppression and social injustice not in a direct and loud way but in a very soft and polite manner. In his following Ddohrra, Tariq raises his voice against religious and communal bigotry.

Assaan Kalhayn Parrh Parrh Anj Thee Ggiyun

Jjull Kaiyheen Day Kole, Nimaz Parrhoon

Hath Bbadh Bhaanwayn, Hath Khol Parrhoon

Ay Phole Na Phole, Nimaz Parrhoon

Hath Tasbeeh, Masjid Raqs Karoon

Paa Ggull Wich Dole, Nimaz Parrhoon

Jith Tariq Darrkay Na Howen

Ooha Masjid Ggole, Nimaz Parrhoon

[Offering prayers in loneliness has made (us) segregated, let’s go and in the accompaniment of someone, offer our prayers

In following lines of his poem, "Chirriyaan Uttho" (Get up, Sparrows), Tariq uses the metaphor of sparrows for the weaker sections of society and ask them not to be disheartened by limitations of their resources. Rather he asks them to use whatever non-violent means of resistance they have at their disposal.

Chirriyaan Uttho, Koi Dhaan Karo

Chupp Na Karo, Chupp Na Karo

Hath Wich Jay Koi Hathiyar Naiyeen

Cheen Cheen Karo, Chaan Chaan Karo

[Get-up, sparrows, and register your cries

In his poetic career spanned over more than six decades, Tariq produced eight books: Gharoon Dar Taannee, Mattaan Maal Wallay, Maikoon See Laggday, Sussi, Main Kia Aakhaan, Hath Jorri Jjul, Bbaytt Dee Khushboo and Umraan Daa Porhiyaa. He became a source of inspiration for many budding Seraiki poets. Besides composing poetry, he nurtured a nursery of Seraiki poets. Indeed, Tariq delicately weaved a tapestry of resistance for which he deserves glowing tributes.