An example of the unpredictability of human life

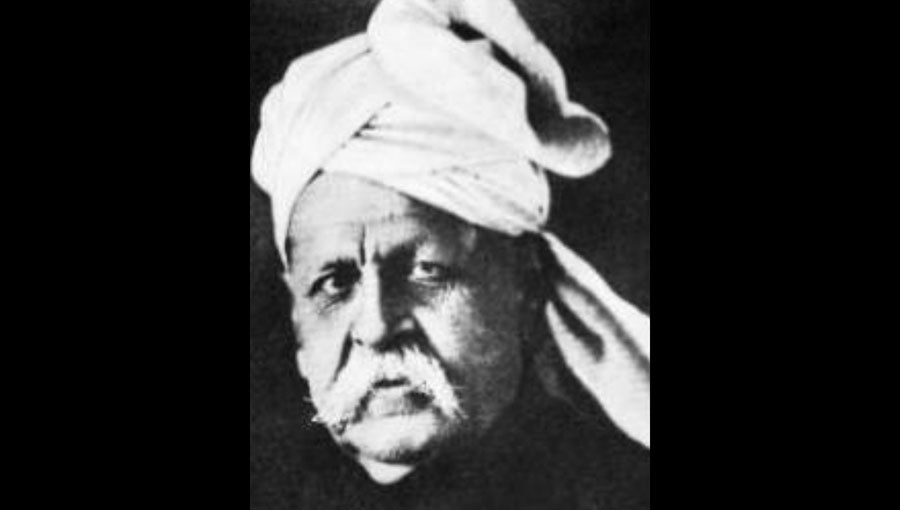

In the previous column on the same subject, I briefly mentioned Lala Harkishen Lal’s enigmatic disposition which I argued is quite common in most self-made persons. It is never easy for anyone to adjust to different realities that present themselves in a radically changed scenario as was the ‘rags to riches’ case of Harkishen Lal.

To start with, he encountered poverty that needed a different set of faculties and mindset. It instils in a person a peculiar worldview that is reflected in his choices, life style and a typical sort of people that he opts to socialise with. After ridding himself of poverty, he enters into a different phase of life. His priorities, people around him that he likes to mix up with, and the taste and choices that he tends to make undergo a volt face. Having said all this, he cannot cast off the shadow of his previous self when he was struggling against poverty.

Thus the two contradictory selves in a single soul conjure up the contradictions in a person like Harkishen Lal.

He built a huge mansion for himself but chose to live in a small room in its top storey, which was "a combined bedroom, dressing room and semi-office". Thus his was an exemplification of a dichotomous life which reflected his enigmatic nature. That aspect in his personality got articulation through different choices which had a lot of bearing in his daily life. For decorating his room, he commissioned an artist to travel across the province and paint portraits of interesting beggars he came across. Around one hundred beggars were painted and the paintings were installed in the room where he lived and did most of his work. If someone asked the raison d’être of those paintings finding space on the walls of his room, he had two explanations to offer: every man shorn of his trappings, is no better than a beggar, and by having these portraits around him, he remembered his own humble beginning.

It is said on the authority of his eldest son K.L.Gauba that "very few persons, who begged at his door were ever turned away". However, the enigma articulated in his taste and choices is worth noting.

Read also: The rise and fall of Harkishen Lal

One of my learned colleagues at the History Department, G. C. University Lahore contests my opinion by asserting that such contradictions are essential components of human life. From the standpoint of a historian, no life is imaginable without contradictions. Harkishen Lal’s rapid rise to fame, influence and fortune exacerbated the contradictions in his personality. His riding with the Lieutenant-Governor on the same elephant to open the Exhibition, and driving about in a vehicle (motor car -- for a long time one of only two motor cars in Lahore) while other people of his ilk rode bicycles or tongas, must have intensified the ambiguous nature of his personality.

It may also be argued that Harkishen Lal might have been gratifying his megalomaniac urge by looking at the portraits of beggars in his bedroom. The psycho-analytical layer in his personality warrants further research.

Now I turn to the downfall of Lala Harkishen Lal, a continuum from the previous column. The fateful era for Harkishen Lal began in 1913 when Arya Samajists became active against him. Arya Patrika, the mouthpiece of Arya Samaj, was believed "to have been promoted with the set purpose of creating a panic among the clientele of the banks in which Harkishen Lal was interested." Such panic wreaks disaster on a business like banking. He started incurring loss.

However, his problems did not end there. Hindu extremists were not his only denigrators; the Lieutenant- Governor Michael O’ Dwyer was particularly allergic to Harkishen Lal. O’ Dwyer’s animosity landed him in jail. In April 1919, in connection with martial disturbances in the Punjab, Harkishen Lal was arrested and then deported and eventually put on trial before a special tribunal on charges of conspiracy and ‘waging war against the King’.

Interestingly, Lala Harkishen Lal ‘wore an air of indifference’ during the proceedings of the trial, and caused ‘no end of annoyance to the presiding judges by appearing in the court in a night-suit and slippers and snoring in between’. The judges ruled against him and he had to serve a jail term though for a very brief period.

After the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms (1919) were promulgated and a general amnesty was proclaimed at the recommendation of Mr. Montagu, Harkishen Lal and his companions were set free. Not too long after, he was made a minister in the Punjab government. He held that portfolio for two and a half years. Then he returned to the field of business yet again.

The People’s Bank of Northern India was the next project that came up in 1925. The Maharaja of Patiala inaugurated it with usual pomp and aplomb. With the establishment of the bank, Harkishen Lal came to command a unique position in the Indian financial and industrial setting. He not only controlled an important bank but also a very important insurance company, which in terms of annual business and premium income was among the first three in India. Besides, he controlled seven flour mills constituting the biggest combination of mills east of the Suez Canal, sugar factories and electric supply companies. He was a chairman of more companies than possibly any other man in India.

Several states and provincial governments sought his advice in the promotion of industrial and economic schemes. As highlighted in the discussion of his enigmatic personality, all this fame and wealth made him act like an autocrat who was rough and ruthless in handling criticism and opposition. This trait earned him many enemies but it also enabled him to hold authority over men, institutions and occasions which for any other person would not have been possible.

The eventual downfall began from 1931 onwards because of the economic depression which particularly hit the banking sector. That was the time his benefactor Sir Shadi Lal was replaced as Chief Justice of the Punjab High Court by Sir Douglas Young. Shadi Lal was positively disposed towards Harkishen Lal and looked the other way regarding complaints about the People’s Bank. With Douglas Young’s appointment, those complaints were brought to the surface and Young encouraged fresh litigation against Harkishen Lal. He was convicted of contempt of court, insolvency and receiverships.

In the midst of these trials and tribulations, Harkishen Lal passed away as a dejected man having led a very eventful life. In Harkishen Lal’s rise and fall lies an example of the unpredictability of human life.

(Concluded)