No actor from Indian cinema in recent memory has become such a prominent public celebrity as Om Puri. Yet his wide-ranging influence was due in large part to the way in which he embodied not one identity but several

"When I was 6-7 years old, I would stand still in the bazaar or atop a railway bridge, and observe life milling around me: a beggar or a rickshaw puller, a rich man or a poor man. The socio-economic disparity between them used to hurt me. I would often question myself: Why has God created such a disparate world? And pray to Lord Krishna that may he give me the strength to do something for them. There was no medium available I could express these feelings in.

I turned out to be a good actor, much praised and loved by public, and through these plays my feelings found a language in the dialogues that were written by other writers. I found peace in them, and got addicted to their nuances. I had made up my mind that this is what I would like to do in life - to act".

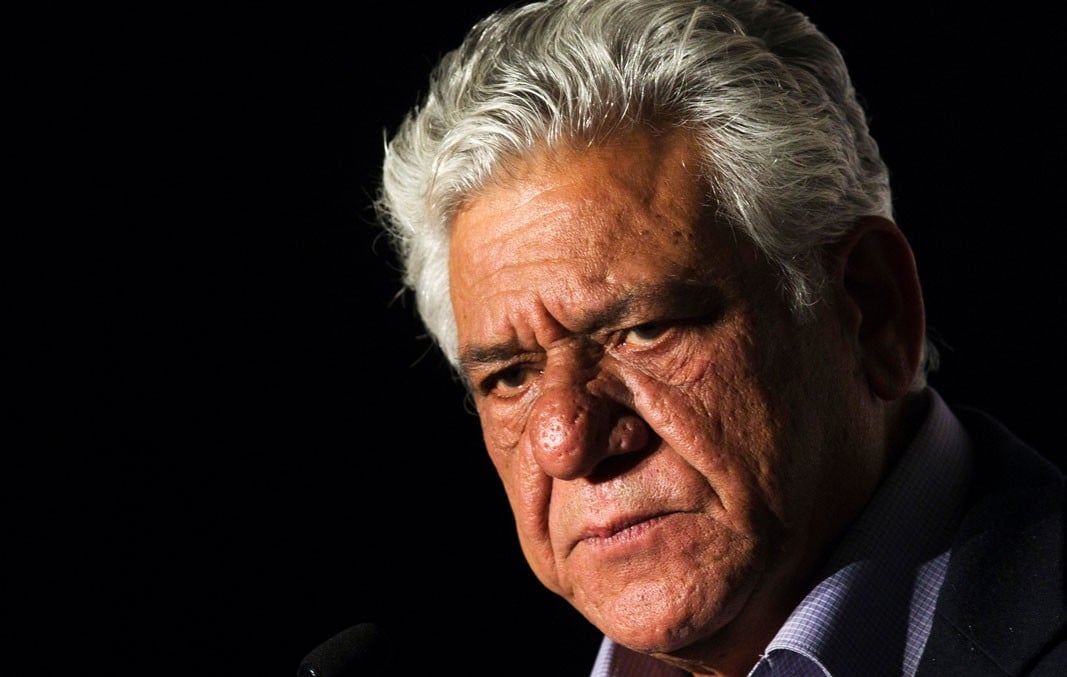

Perhaps no actor from Indian cinema in recent memory has become such a prominent public celebrity as Om Prakash Puri. Yet his wide-ranging influence was due in large part to the way in which he embodied not one identity but several.

Born on October 18, 1950 in Ambala, he pasted billboards and posters and worked as a make-up artiste for a theatrical group before joining Roshan Alkazi’s National School of Drama on scholarship for three years. Soon after, he enrolled at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune upon his friend Naseeruddin Shah’s insistence.

He played a leading role in developing acting as a paradigm of critical investigation disseminated across the humanities and social sciences, from media studies and sociology to history and political philosophy, by a generation of younger actors who took culture seriously as a material formation inscribed within contested relations of power and resistance. In his role as an actor par excellence, he reached a broad audience beyond the confines of academia, introducing his method to those entering the field as working adults by way of his broadcasts as well as his onscreen presence.

But the archive of Puri’s prolific cinema and television appearances reveals something more. With his ability to win the attention of a wide audience without ever compromising his critical acumen, Puri was a cultural theorist who fully understood that the form and the medium of communication carry signifying power in their own right. Whether in Shyam Benegal’s Bhumika or Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh, his animated and inquiring tone of voice was always capable of turning the conversation in new directions. Indeed, what made Puri so singular was that his media appearances were not distinct from his commitment to his art: All were fully integral to the interventionist ethos of his lifelong intellectual activism. Far from passively reflecting a given public, Puri’s discourse actively brought multiple publics into being.

All this made Om Puri something of a modernist, in the sense that his interventions cut into established ideological fixities, calling forth new possibilities in cultural life. Breaking up commonplace perceptions in acting of the social world as immutable and unchangeable, Puri acted on a repertoire of diagnostic skills that laid bare the stakes of each topic he addressed through his acting, giving culture and art a pivotal role in making future alternatives thinkable. Antonio Gramsci’s motto "pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will" was Puri’s modus operandi at all times.

When I first met him, I was in awe: his warm accessibility welcomed everyone into the conversation, and his generous attentiveness had everything to do with the egalitarian ethic he embodied in all that he did.

In a tribute to the great actor Om Puri published shortly after his death at 66 on January 6, fellow actor and sometime collaborator Anupam Kher remarked that Om Puri had died a lonely death. In a late interview, Puri spoke of his sensitivity to the melancholy of his source material. Over time, he mused, all our lives are failures. But his ghostly final films, Salman Khan’s Tubelight and Nandita Das’s Manto, to the contrary, were virtuosic reflections on life, fiction, and misperception that in their self-referentiality induce the viewer to remember and review the full sweep of Puri’s acting career.

The passage between life and death had long preoccupied Puri. His awareness of the dead and of their insistence in the lives of the living, and of the capacity of cinema as a medium for reflecting on this commerce, this debt, is perhaps his most extraordinary contribution to world cinema. One immediately thinks of his controversial, coruscating Sadgati by Satyajit Ray, based on Munshi Premchand’s short story. In a passionate acclamation of the film, one of the critics argued that cinema like this was capable of approaching the limits of a distorted humanity.

By White Teeth, Om Puri moved further toward the internal, artificial modes that make his later career, as he increasingly chose studio settings and stylised action. Exploring the infinitely fine folds in the human psyche, addressing our opacity to ourselves and to others, capturing the allure and terror of the intimation of other lives we might have led, other choices we might have made, Puri’s films and characters discover cinematic modes of representation that hold and give form to feelings. Heightened sensitivity, sureness of touch, and unfaltering artistic integrity beribbon Om Puri’s career and now ensure his legacy.

In his later years, Om Puri had taken on the terse, attenuated air of a Catholic abbot. Podgy, austere, his eyes a cool, penetrating brown, he embodied the rationalism and restraint for which his cinematic style had become famous. Whether his fidelity to a modest theme and manner (as in Susman), stated early and slightly refined throughout a long career that seemed oblivious to worldly tumult, was resolute or reactionary, the art of a miniaturist master or of a trivial philosopher cautiously tending his square centimetre of bourgeois insight, depended on whether one felt, as Puri once claimed, that the artiste’s role was to organise pleasure.

From the hot August streets of his debut Ghashiram Kotwal in Marathi to the radiant arcadia of The Mystic Masseur, the intent limitation of his style and purview, resulted in plenitude, a gracious bounty of social perception, and indeed, of highly organised pleasure.

Puri imbibed the lessons taught by Alkazi while doing street theatre by Shakespeare, Lorca, Brecht, Safdar Hashmi and Badal Sircar, both as a spiritual guide and as aesthetic instruction. However stylised or artificial his acting would occasionally become (such as in My Son The Fanatic and Chachi 420), Puri maintained an almost religious adherence to realism, to a simple unmannered rendering of the world whose clarity, plain arrangement, and quiet precision bespoke the rationality of his thought.

The characters that he played search for happiness, truth, self-knowledge, but mostly they seek love, and for all the cool classicism of the masters’ mis-en-scene, they frequently desire an all-consuming, engulfing love, or one that "burns", as Rekha muses in Aastha.

Recipient of Padma Shri and OBE, Om Puri’s work as an actor cannot be straightforward. At the very best, it is to talk about the complex, nested work of producing, eliciting, and projecting a proposition into multiple worlds through countless performances that produce many kinds of impact.

Om Puri died of a massive heart attack on January 6, 2017. He was found dead in his Lokhandwala Oakland Park apartment in Andheri, Mumbai.