The Annual Degree Show at NCA seemed to equate opposing forces to artistic intention and its very absence

"Art that actually works, makes its mark on reality."

The Annual Degree Show 2016 at the National College of Arts, Lahore, pursued the same individualistic politics of survival this year. The social media hype that surrounded it and the discussions affiliated with it developed a notion of engaged art in the best avant-garde tradition: Of art as a tool serving political causes and turning "spectatorship into citizenship", which is convincingly pitched against autonomous art that is still "aestheticizing reality, changing ideas into spectacle, and transforming the political into a call that no one follows."

In order to find art that brings change, art that is not critical in an empty fashion, the audience looks towards the NCA which is said to showcase the best and the most contemporary of art trends in the country. It may be true that people who have stumbled into art when they were supposed to be working in other fields…in parliaments and government, or in the media…or even therapists and doctors, may well have made it big as retail businessmen and/or bankers, had they not ended up pursuing a degree in Fine Arts by sheer irony of fate.

The Annual Degree Show 2016 was anything but a risk-taking mission. This does not mean that it was dull, necessarily, but rather that the context has become so bland, its organisers so resistant to more ambitious and critical curatorial propositions, that it is almost inevitable that we keep seeing a very similar, at times uninspiring, affair: An overview of the latest trends in the visual arts, lined up one after another without much intellectual gravity. Some of the works suffered from inconsequential themes and even more ridiculous titles devoid of any concrete meaning.

The approach to art making gave the whole endeavour a slightly safe feeling this year - geared less toward risk than control. Overall, though, the project managed to play in several registers at once, exploring philosophical themes of interest to a local audience while also inserting some shortcuts and fashionable streaks, known only to specialised circles. Such modishness is, in fact, another point of criticism. More than forty artists were given room, with a wide selection of works by each of them on display. The pieces exhibited in the first three galleries had a chance to be in the spotlight. Yet despite the polyphony of voices, all seemed to sing to one clear tune. This could have been a ballad or a litany on obsession, the soundtrack to making forms through the almost sacred pain of repetition, like Shajia Fatima’s organic forms in epoxy resin and metal.

The Degree Show offered a fittingly more institutional format, flush with engrossing installations joined by a cohesive curatorial layout that snaked from one idea to the next. The first floor dealt with psychological and phenomenological wanderings as figures of narrative, epitomised by Abdul Aziz Meer’s smoked waslis and Khadijah Rehman’s rather disturbing take on mortality, inspired by T S Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland’ and ‘The Lovesong of J Alfred Prufrock’.

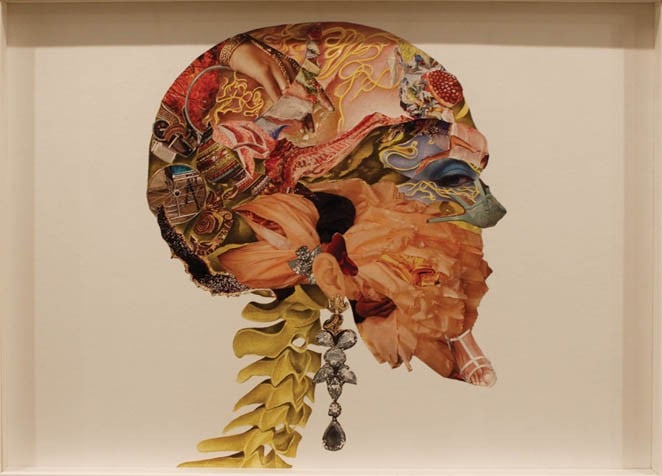

The strongest overall section was the last floor, in which personally wrought mythologies exploded in a variety of metres and styles, perhaps making this floor as a curatorial ground zero. The best works in this section included Muhammad Muzammil Khan’s realistic renditions of demolition sites in miniature, Amna Rehman’s bold allusions to alternative sexuality, Imran Kazmi’s breathtaking rose petals, and Kashif Mangi’s take on the world of Pakistani cinema hoardings and advertisements. The denouement on floor three was a smaller and more disjointed grouping of artists plumbing the grandiosity of history, with an austerely academic three-part riddle by Somia Khalid, a room scrambling spatial, virtual and linguistic systems of meaning-making, and recent works by Haya Zaidi fusing kitsch and antiquity into a readymade souvenir of market-automated art history -- in which Wangechi Mutu meets Hieronymous Bosch meets Saba Khan.

Aesthetically rote displays in the Miniature Studio, on the other hand, had no place in a serious show, whether it was Muhammad Salman Khan or his neighbour Manzoor Hussain. The only saving grace in his particular section was Kiran Waseem’s eerie nightscapes that dangled between memory and time.

Porous sightlines are an insubstantial means of linking the works on view, most of which seem to be placed randomly or, worse, grouped by their basic formal similarities: Haseebullah Zafar’s limpid terra cotta pieces, or Masood Ahmad Subhani’s outsized impressions of rust on canvas that reminded one of early American Abstract Expressionists, such as Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell.

Nevertheless, three of the most exciting works were here: Noor ul Ain’s absurd but somehow organic combinations of animate and inanimate patches (perhaps borrowed from nature reminiscent of Adolph Gottlieb) undoing their individual meanings as they constituted and reconstituted a constantly unstable tumult of signs. Other highlights were paper and metal mechanical monuments like Nakshab Rehman’s ‘Portrait of a Friend’, Sadam Murad’s ‘Supremacy’, Noshad Ali Khan’s remarkably executed ‘A Smile in the Mirror’ and Tahir Zaman’s oils on paper.

The contingency of the Degree Show has, in the more utopian moments, been thought to be its strength. Rather than a slow-moving museum, degree shows can be flexible and responsive -- to time and place. NCA’s Annual Degree Show was shaped by both an awareness of the urgent obligation to respond, and the knowledge that any response would be inadequate. It felt trapped. But this provided an interesting case. When a cultural institution is so thoroughly enmeshed with private interests, the same interests that are transforming the fabric of the metropolis, how is it possible to stand out?

The Annual Degree Show 2016 seemed to equate opposing forces to artistic intention and its very absence. Works that seemed unfinished (or unresolved) or were themselves accounts of failure underlining this poignant array; a testament to artistic labour, the toil of an artist or those who would only later be regarded as such. Whether in paintings, drawings, prints or sculptures, these young graduates all address the same question and seem to be caught in the very act of creation, standing at a crossroads between life and death, intention and accident, pain and pleasure.