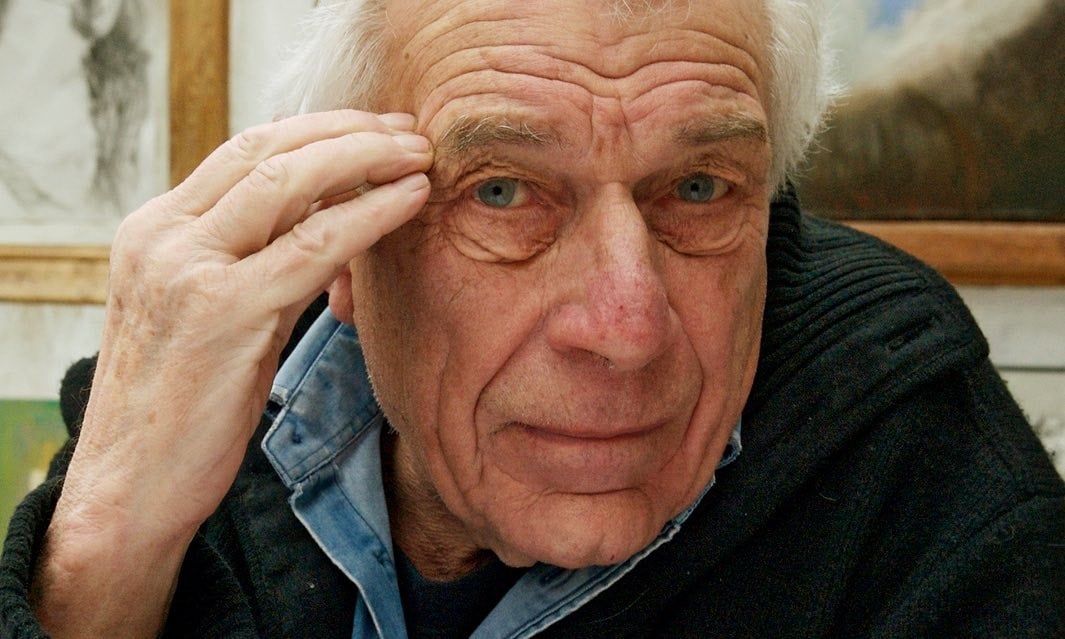

One of the most accessible and exciting critics of our times who contributed as much to the art around the world -- by showing a way of approaching art as part of life

One has seen books like Landscapes: John Berger on Art and Portraits: John Berger on Art. Unfortunately, there is none about John Berger on Life or John Berger on Death. This seemed like a much-needed one after one heard the news of his death in the early hours of Tuesday last.

The cold Tuesday night reminded me of another freezing afternoon several years ago in Lahore. It was Christmas Eve, when driving through a busy street near Regal on Lahore’s Mall Road, my cell phone started ringing. The number flashing on the screen was unfamiliar. Curious, I answered the phone not knowing who would be calling me at that hour from London and that too on a public holiday, a day of general festivity when no business is conducted. It was John Berger on the other side, introducing himself and explaining he won’t be able to contribute an essay for the forthcoming issue of Art Now Pakistan, the online magazine for which I had requested his submission in my humble capacity as editor.

Hearing Berger on the phone was like listening to a hero presenting himself to a minion. John Berger in his frail voice was stating the reasons why he could not send in his piece. He said he was too old to write anything new, and that I could include a chapter from his collection of The Shape of the Pocket instead.

I had been teaching the art of Surrealism as an entity removed from reality for years. That winter day, I felt Surrealism as part of my surroundings. I was listening to the typical British accent of Berger while making my way through the narrow lanes of congested Lahore, wondering how could two distant and parallel hemispheres exist at the same time: the voice of a person who had moulded and shaped my thoughts, and the spread of shops at an ordinary market in Lahore.

Receiving a phone call from one of the masters and mentors of art criticism was incredible. It seemed as if words from his much-adored books had come to life.

Until you meet or interact with an author, his writing is just a variation on language. Once you have heard him speak, every word of his, no matter if it’s a text message, an email, essay, short story, or novel, invokes the voice of the author. For me, there was a phase before talking to John Berger and after. Actually, there was hardly a difference between the two because as an art student I had a chance to read his remarkable book, Ways of Seeing, that enlightened and enriched me with the intricacies of art theory.

Through this thin volume, like millions of art students around the globe, I came to know of the intention inherent in depiction of Dutch landscapes and objects of still life during the 18th century. According to Berger, in both the genres, the artist was employed to impress the audience with his patron’s power to accumulate a great spread of land and the ability to acquire expensive and exotic edible stuff.

This ability to discern a new dimension of visual arts distinguished Berger from other critics. His Marxist approach opened new ways of seeing the pictorial constructs; often analysing them without any consideration or pity.

For example, talking about the tradition of portrait-making, John Berger comments on how the invention of photography became a factor for artists to discover and stress on capturing the essence (soul) of their models. They know that the camera which can produce the likeness of a person in a quicker, accurate and less expensive scheme would put them out of business. So they forge the notion of portraying the psyche of their subjects on a canvas.

The analysis of John Berger which inspired and influenced innumerable people is found in his essays on art and artists, published in separate volumes and also available in one, The Selected Essays of John Berger. In some of these, one is unable to separate biographical/personal details from the practice of the artists. Especially his amazing observations while discussing the art of Giacometti where he conjures up the reasons for the Swiss sculptor’s preference for lean, elongated figures, based upon the picture of the artist crossing the street in rain wearing his overcoat to his studio. The stylised forms created by Giacometti in a way resembled himself in his solitary walk.

Likewise, talking about the atmospheric landscape of Turner, John Berger mentions the barber’s shop of Turner’s father, where the exposure to foam and steam had a decisive role in formulating the aesthetics of the painter.

Ideas of such insight made Berger one of the most accessible and exciting critics of our times. The gift of stating facts which are there but are oblivious to an ordinary eye/mind was a mark of his genius. For example, in his book The Success and Failure of Picasso Berger says: "Whatever he wishes to own, he can acquire by drawing it. The truth has become a little like the fable of Midas. Whatever Midas touched, turned into gold. Whatever Picasso puts a line around, can become his".

Apart from art criticism, Berger was also fiction writer, winning Booker Prize for his novel G.; and a painter too. In his book Bento’s Sketchbook, one enjoys the writer’s sensitive drawings, and comes to know that when he talks about art, he is not discussing it in a detached tone; his words are daubed with the warmth, sensibility and sincerity of the image-maker.

Perhaps this quality has made John Berger different from the contemporary art critics. Instead of venturing into obscure and obtrusive expressions, his writing is simple, clear, convincing and inspiring. His style is not a formal choice; it reveals his unbound commitment to reach people across classes and classifications.

It was through the mediation of one of his life-long friends that I had contacted him to write an essay for Art Now Pakistan. His decision to call the editor of an online art magazine in Pakistan was a remarkable act of shunning the barriers of fame and prestige. He wanted to connect to an audience so remote from mainstream art but couldn’t due to his old age. Mesmerised, shocked, I was unable to tell him that he has already contributed to the art world of Pakistan, and art around the world-- by showing a way of approaching art as part of life: A life that continues after death just like the life of John Berger.