Reaction to any reinterpretation of Jinnah shows how ‘ideology’ still plays a critical role in the country’s affairs

A few days ago, the blog of lawyer Yasser Latif Hamdani was taken off the website of an English daily because of threats against not only Hamdani, but also the newspaper and its employees. While in normal circumstances I would have blasted the newspaper more, perhaps the current reality in the country makes one become a bit too careful. But still it is rather sad to see the removal of a rather academic and well-argued article. This incident certainly raises a few critical issues.

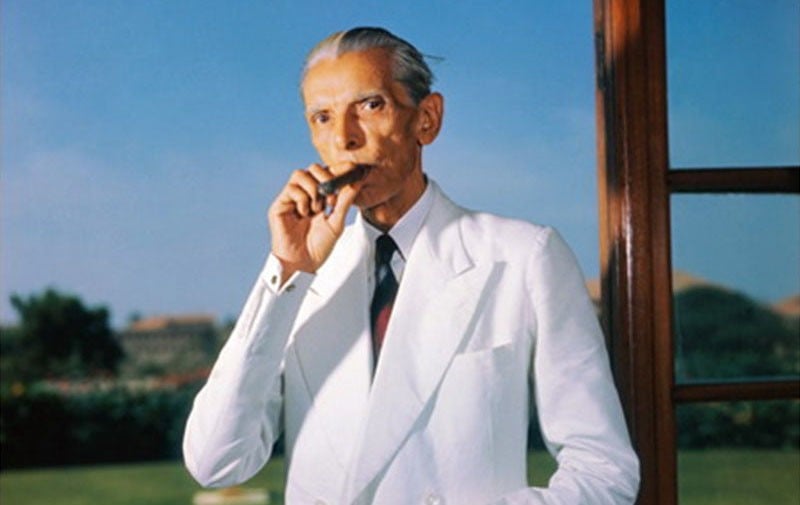

It is surely very strange that even after nearly seventy years of the death of the founder of the country, there are scores of people in the country who cannot tolerate any interpretation of him other than theirs. In fact, they are so intolerant of another view that they threaten -- and who knows, maybe even kill -- someone to defend their view of the ‘Great Leader.’ I also find it fascinating that this has happened not to anyone who criticises Jinnah or takes his views more critically, but to someone who is perhaps even a self described Jinnah-phile. (Here in the interests of full disclosure I should mention that I have had a number of debates and disagreements over Jinnah with Mr Hamdani).

So if people cannot tolerate a different opinion of Jinnah from a person who thinks that Jinnah is the best thing that has ever happened, then what about those who interpret Jinnah in a more nuanced manner?

Associated is the issue that this reaction, I reckon, was not from the semi-literate public, but from people who at least read newspapers and blogs online and are reasonably versed in English and discourse. As this was a blog, and not an opinion piece, it was limited to an online audience, and so its readership was fairly limited by age, social background and education, I surmise. Hence, this situation is even more worrying.

One reason why we are still unsure about Jinnah and his thinking is that he was a very cold and quiet person who simply kept to himself. We can count on one hand the people he would regard as ‘friends’, he didn’t leave many personal papers (here I am differentiating official papers from personal ones which tell us about the ‘person’), and died too early and quickly for the new country to be sure about what he wanted or had planned to do. That said, Jinnah noted several times after the creation of Pakistan that its future was the responsibility of its ‘people’; it is people who will decide what direction the country would take, and so it should not be dependent on what the Founder thought or wanted. Jinnah had hoped that Pakistan would become a democratic country and, therefore, this was the obvious thing to say and maintain.

I often wonder why does Pakistan treat Jinnah in this hallowed manner, while in India it would be bizarre if Gandhi or Nehru are treated in this manner. In fact, the current BJP government in India thrives on its anti-Gandhi and anti-Nehru stance, and promotes Sarvarkar and Shivaji -- at some level the antithesis of the aforementioned gentlemen, as ideals. The reason for the difference is simple, yet profound.

India developed on the path to democracy and then progress while Pakistan didn’t, therefore India continued to highly regard its elected leaders -- while also criticising them -- but Pakistan did not have this luxury. Its first elected leader -- if one might call Zulfikar Bhutto that, was a megalomaniac and did more to undermine Pakistan, its state and society, than perhaps anyone before him. After him we have only had his daughter, the martyred Benazir Bhutto and the current prime minister, so not many people to look up to.

This ‘gap’ in Pakistan has led to a deification of the founder of the country and his official legacy. Since Pakistanis do not have anyone else to look up to, they have put the founder of the country on such a high pedestal that he had become ‘Rehmatullahalaih’ -- something which he surely would not have countenanced. But he had to be put there -- he had to become that untouchable (in the completely opposite sense!), so that ‘Jinnah’ and ‘Quaid-e-Azam’ become the first option for every road, stadium, power plant, university etc in Pakistan. The more things are christened with Jinnah’s name, the better we feel that the work has been done properly -- a simple, shallow, yet satisfying ritual.

Associated is the reality that with the deification of Jinnah, we have gone almost insane trying to undermine others, so that no one is left to even come near the stature we have been according Jinnah (and of course Iqbal who we belatedly discovered mainly in the 1970s).

Reaction to any reinterpretation of Jinnah also shows how ‘ideology’ still plays a critical role in how the country is imagined and, most importantly, lived. It is not some inconsequential debate that scholars have in their classrooms or evening gatherings, it elicits a reaction from people from all sorts of backgrounds, and borders on the violent. It also helps us understand how ideologies like Islamic State, the Taliban, among other things, take root in societies like Pakistan. A number of commentators have often said that ISIS perhaps will not get a firm foothold in Pakistan, but incidents like these certainly point out a rigid ideological bent, which if harnessed carefully, can lead to a very scary outcome.

So what can be done? While tomes can be written on this subject, let me just point out one, which brings us back to the founder himself. Since this piece will come out on New Year Day, let me be counter-cultural and call for turning the clock back to Jinnah, and argue that ‘Pakistan should be for the Pakistanis’ whoever they might be -- ethnically, culturally, religiously or otherwise. This was the essence of Jinnah’s August 11, 1947 speech and this is one of the primary things which we need to focus on now if we are to literally save ourselves.

If Pakistan is composed of all those people who are living within its boundaries and who profess a common citizenship then a myriad of our problems can be easily resolved. This is what Mr Hamdani was also trying to articulate in his article, and this, on his 140th birthday would also make the founder happy.