Al-Farabi, Thomas More and utopian literature across centuries

Recently Thomas More’s Utopia turned 500. For observers and students of socialism and related political ideologies, this quincentenary sparked an interesting rethinking about the desire to establish an ideal society. Be it the experiment of the collapsed socialist societies in the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries or the Iranian revolution of 1979, or even the recent attempts by the Taliban and Islamic State (IS) to establish a perfect Islamic society, all in the process have killed thousands of people and suppressed dissent.

Hilary Mantel’s historical novel Wolf Hall (2009) beautifully captures the events leading to More’s death but even more interesting is the detail about how the writer of Utopia himself indulged in persecution of ‘heretics’.

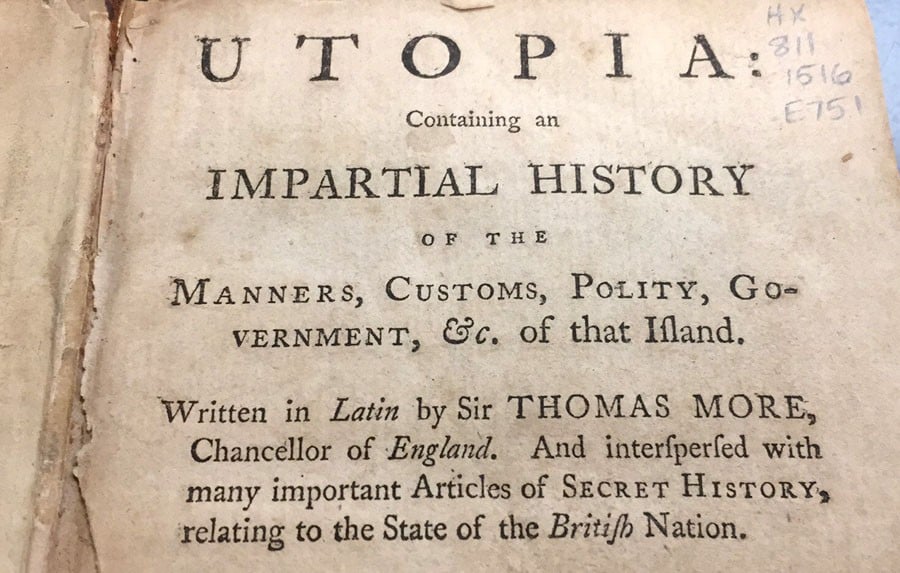

Thomas More’s Utopia is probably the most cited book of the utopian literature so much so that it introduced a new term used in almost all other languages as it is. But before discussing Utopia, a look at the commonly overlooked but important work by one of the greatest thinkers in Muslim history - Abu Nasr Al-Farabi’s Al-Madina al-Fadila is in order.

Al-Madina al-Fadila has been translated variously as the Perfect State or the Virtuous City -- written in the early 10th century i.e. almost six hundred years before Thomas More. Al-Farabi - known in the West as Alpharabius (870 - 950) was a renowned philosopher and jurist who indulged not only in ethics, logic, metaphysics, philosophy, and political science, but also in music. Though, before Al-Farabi at least two other major writers had contributed to such literature i.e. Plato in his Republic written in the 4th century BC and Augustine of Hippo in his City of God nearly a thousand years later, the beauty of Al-Farabi lies in his representation of religion merely as a symbolic rendering of truth.

Both Plato and Al-Farabi look up to the philosophers to provide guidance to the state, but to sugarcoat his philosopher -- and perhaps not to invite the ire of religious leaders -- Al-Farabi calls him a prophet-imam instead of the philosopher-king by Plato. When you go into the details you find that Al-Farabi wants his imam or ruler to be more like a philosopher than a prayer leader. He should rule by an ‘innate disposition’ and exhibit the ‘right attitude’ for such rule. The ruler should have ‘perfected himself’ in many disciplines and with the command of good language should be able to communicate his ideas to his subjects effectively.

‘Active intellect’ is one of the primary traits Alf-Farabi wants to inculcate in his king, giving a clear hint that if a religious leader does not have such an intellect he has no right to be the ruler. In addition to good memory, the ruler should have a ‘love for learning’ and ‘good understanding’. Here Al-Farabi prefers learning and understanding over memory, indirectly showing that most religious leaders rely on their good memory to impress their audiences, rather than encourage wider learning and comprehension. This rings so true even in our own age of televangelists and quote-loving quacks.

Al-Farabi’s virtuous city embraces the pursuit of goodness and happiness where virtues abound, just like in a ‘perfectly healthy body’ – both intellectually and physically. In contrast, his ‘corrupt city’ is ignorant (jahil), without ethics (fasiq) and directionless. He places much emphasis on people’s cooperation to gain happiness. He clearly anticipates that the ‘virtuous world’ will emerge only when all its constituent nations collaborate to achieve happiness. Here he goes much broader than how two of his predecessors mentioned earlier -- Plato and Augustine -- delve in the Republic and the City of God.

In some parts of the book, Al-Farabi mixes religion in a way that contradicts his own writing elsewhere. It seems that he tried to confine his independent thinking within the mould of contemporary religious thinking without antagonising the religious fanatics that were as abundant then as they are now. Living in the 10th century amid the decline of the Abbasid rule and with chaos all over the Muslim world, Al-Farabi reflected his desire for a peaceful and prosperous world. Jumping six centuries forward, you look at Thomas More’s Europe, and you find the early 16th century again mired in religious tyranny and conflicts.

The invention of press by Gutenberg in Germany had facilitated rapid spread of books and ideas. In the second decade, at least four major pieces of writing were completed: The Prince by Machiavelli in 1613; Utopia by Thomas More and The Education of a Christian Prince by Erasmus, both in 1616; and the most devastating of them all, Ninety-Five Theses by Martin Luther in 1517 against Catholic indulgences. The Prince is basically political advice to rulers on ‘realpolitik’ of that period, advocating a separation of politics from ethics, in the direction of the ‘practical’ enhancement of the state’s power.

One might argue that The Prince and Utopia are two entirely different books with dissimilar foci, but looking closely one finds many similarities too. A common streak in most utopian literature from Plato and Augustine to Al-Farabi and More -- or even later in Huxley and Orwell -- is an overlap of normative and at times satirical description not only of the state but also of its ruler. Talking about More, two pieces of recent literature must be mentioned. First,A Man for all Seasons by Robert Bolt (1924 - 1995) is a play written in several versions in 1950s.

This play about More was made into a multi-Academy Award winning movie in 1966 with Paul Scofield playing the lead role of Sir Thomas More. The play and the movie present More as a saintly figure who as the lord chancellor refuses to endorse the divorce of King Henry VIII from his wife Catherine of Aragon. He prefers death over compromising his principles and the play leaves the audience in awe of Thomas More. The second is the novel Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel which presents Thomas More as a zealous heretic-hunter. It questions More’s saintly place in Tudor history.

Interestingly, heresy-hunting became a central concern of Thomas More after writing his Utopia that talks about an ideal state. More became increasingly against the threat of heresy and used vehement language with a penchant for hyperbole. In Utopia, More’s imaginary country is totalitarian par excellence without any pubs, brothels, and devoid of any place where people can meet privately or secretly. More’s state is also against discussion of public matters outside of the popular assembly. In Utopia, More repeatedly reminds his readers of the importance of community to keep people united.

To him, self-interest is the destructive force that tears apart the bonds of social unity, and in his ideal locality there are no locked doors and no personal possessions. On the positive side, political power is shared and he suggests that the authority should reside in the body of the people -- much in the same fashion as later experiments in various types of democracy claimed. Councillors and their prince are elected and make decisions in regular consultation with the people. As in Al-Farabi’s book, there is such a contrast among the various postulates of More in Utopia that one wonders how they could be reconciled.

For example, while suggesting a sharing of power he prohibits public discussions other than in the assembly; if anyone is found discussing the public matters outside the only legal public forum, his crime is punishable by nothing less but death -- apparently to avoid any division and distortion of public opinion. The same year that Utopia was written, another relatively lessor known book came out -- The Education of a Christian Prince by Erasmus. This book is closer to the Prince by Machiavelli than to Utopia. The difference is that Erasmus advises on ‘how to be a good Christian prince’, whereas Machiavelli was least concerned about Christian ethics -- or any ethics for that matter.

It needs to be clarified here that though The Prince was written in 1513, it was published much later in 1532 so there is no chance that Erasmus could read it, rather he developed his own independent work. Erasmus book is different from The Prince and Utopia also in its focus on education and the qualities of a good teacher, making it a valuable contribution to pedagogical canon too. To Erasmus, an ideal teacher is of gentle disposition and has unimpeachable morals. That reminds us of the Chinese communist leader Liu Shaoqi ’s booklet How to be a Good Communist used by pro-Chinese communists from 1940s to 1990s.

Despite its contradictory propositions, Utopia spawned a plethora of utopian literature in the centuries to come. Within a century, in Italy, Campanella wrote City of the Sun (1602) -- a philosophical work written shortly after his imprisonment for heresy and sedition. In Germany Valentin produced Christianopolis (1619), advocating educational and social reform synthesising science and Christian ideals -- just like Al-Farabi had tried to synthesise Islam with independent learning. But, perhaps the most impressive work came from Francis Bacon, the founder of modern scientific method focusing on orderly experimentation. His political science completely separated religion and philosophy.

Bacon’s utopian novel New Atlantis was published in 1627. It begins with the description of a ship lost at sea and carries its passengers to an unknown land. The book’s recurring themes are enlightenment and dignity. Though in the new land, religion does play an important role, it is mostly for cover-up; he promotes science as the new religion. But again, like Al-Farabi he held that there were religious laws that must be obeyed. One wonders why most of the so-called ideal states have focused excessively on ‘discipline’ regarding religion and other ideologies -- be it socialism, capitalism, or theocracy -- touching the boundary of repression.

Even the modern states that claim to be the biggest democracies such as India and the US -- leaving aside the countries ruled by Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin - have seen periods in their history when in the name of discipline, dissent was crushed. To conclude, one may hope that efforts to establish an ideal society continue, with a balance in individual and societal interests based on independent thinking, rationality, and artistic and scientific creativity, rather than with skewed ideas about discipline and uniformity that crush individuality in the name of national and state interests.