Of days spent at the boardinghouse at Mansehra’s Bolton High School

Our high school in Mansehra had a British-sounding name: Bolton High School. It was a boarding school. The school was named after Horatio Norman Bolton, twice Chief Commissioner of the then North West Frontier Province, between 1923 and 1930, who had sanctioned the school. (Chief Commissioner was then the chief executive of the province; the office later replaced by that of Governor.)

But there was nothing British about the school except, perhaps, the architecture that the British employed in the hilly areas: Sloping tin roofs -- painted red or green -- extensive verandas; dressed-stone walls; and large glass-pane windows. Located next to the main school building, removed by a volleyball court, was the boardinghouse.

By the time I joined the school, in the 1950s, the only reminder of Mr. Bolton was a large, faded cement plaque on an outside wall of the school that read: Bolton High School Mansehra -- 1926. However, no one seemed to know who Bolton was or why the school was so named.

The boardinghouse, a small building, consisted of three large rooms -- numbered 1, 2 and 3 -- a superintendent’s room, a detached kitchen, and a dining space. Each room housed 8 to 10 students. I was one of the 30 odd boarders. This was my first experience of being away from home, and I didn’t like it.

No one explained to us the rules of the boardinghouse, if there were any. There were rules though, which we discovered as we went along -- or when we broke one and faced the wrath of the superintendent. Sahib Shah was his name, and he was not a kindhearted man.

We were required to bring our own bedding and charpaai (cot) -- yes, a charpaai, too, and a laaltain, (lantern). Electricity hadn’t come to Mansehra, yet. And, of course, everyone had his own tin trunk, which served as storage, safe and a closet. I was allotted a spot in Room No. 3, which housed junior students, and that was where I put my charpaai.

What I remember the most about my brief stay in the boardinghouse was being hungry: Both the quality and quantity of the food we received left us craving for something to eat all the time. Like others, I, too, supplemented my food supply with homemade kulchas and pakwaans that my mother so lovingly made for me to take away when I visited home over the weekends. But even that didn’t help. And, the cookies I brought often got stolen. My two senior cousins, who lived in a different room, knew exactly where I kept them.

A bell would announce the lunch and supper time. At the sound of the bell we would rush to the kitchen -- a smoky, makeshift structure located separately from the boardinghouse -- pick up a metal plate and crowd around Gul Baba, the cook. Gul Baba, probably in his 50s, wore a grey beard and a cheerful expression. It was because of his grey beard that everyone called him Baba (old man). Everyone liked him, not only because he was the food-giver but also because of his friendly nature.

Carrying our metal plates, we would elbow our way to be closest to Gul Baba to be served first, just as chicks wiggle their way around a feeder. Out of a cauldron that sat over a hearth of burning coals, Gul Baba would ladle whatever he had cooked for the day into our plates. We carried the plates to the "dining room", holding them with both hands and walking carefully over the uneven ground so as not to spill the contents.

The "dining room" was actually a side veranda of the boardinghouse, enclosed by a jafri -- a wooden lattice. A few narrow tables set in a row made one long dining table, with wooden benches set around it. We took our seats at the dining table and waited for Manu Kaka to hand us our ration of two loaves of flat bread, naan. Maanu Kaka was a younger man. Younger than Gul Baba, that is. He, too, wore a beard, but his beard was mostly black, which earned him the honorific Kaka (uncle) instead of Baba. While we ate, Manu Kaka stood by with a bucket of water and a few metal tumblers to hand out water around the table.

Other than waiting at the dining table, Manu Kaka also dispensed kerosene oil once a week for our laaltains. On the given day, he would ring a hand bell, and we would gather behind the superintendent’s room carrying our laaltains. He would then bring out a tin canister of kerosene oil from the superintendent’s room, set it on the ground, break the round seal on its top, opening a hole, and then siphon out the oil by inserting a hand operated tin contraption, which looked and acted somewhat like a bicycle pump. As Manu Kaka cranked out the oil for each laaltain, we sat around him on our haunches keenly watching the procedure, fascinated by that scientific marvel -- the pump -- that made the oil travel up the height of the canister into our laaltains. At that young age, and those times, that tin pump looked like awesome technology.

Presiding over the establishment of the boardinghouse, as I mentioned earlier, was Sahib Shah Master, a Kakakhel from a nearby village, Girwal. He was an Urdu teacher. We always used the title "Master" at the end of his name rather than in the beginning, as we normally did in the case of other teachers, probably because it rolled off the tongue more easily.

Sahib Shah Master was a rotund man with a thick, flowing beard. (It seemed a beard was mandatory for the boardinghouse establishment.) He wore a kulla (a hard turban) and a harsh expression. He was always angry with someone or at something. He was angry when he thought we were making too much noise. He was angry if we went to the bazaar after school, which was a sure sign in his eyes of us going morally astray. He was angry if we gave our laundry to the dhobi; it was extravagance, he said. He expected us to take our laundry home over the weekends or wash it ourselves. Worse, Sahib Shah Master would become a raging bull if we didn’t get up for our fajar prayers. He would storm into our rooms before daybreak, just when slumber is sweetest and deepest at that young age, shouting and brandishing a stick. He didn’t hesitate to use the stick if anyone took too long to jump out of the bed.

Before we retired to our rooms at night, there would be a roll call. We would assemble in the courtyard and stand in a semicircle facing Sahib Shah Master who sat on a chair. The monitor, one of the senior students, stood next to him holding a laaltain for Sahib Shah Master to read the names from the register. After the roll call, the "felonies" and "sins" committed by any of the boarders that day would be announced and the "culprit" asked to step forward and explain his position.

Regardless of the explanation, Sahib Shah Master would get up from his chair and with a long, thin and flexible stick -- more of a whip -- hit the accused at his ankles: One, two, three, and more times, depending on the severity of the "crime". While the victim yelped and jumped in pain, Sahib Shah Master had a fiendish expression on his face. The rest of the group watched the spectacle in silence -- terrified.

Craving for food all the time and having to live under a constant threat of violence by Sahib Shah Master, I found it difficult to settle down, and started missing home. I especially missed my mother -- both her love and her cooking. I started counting the days when I could go home.

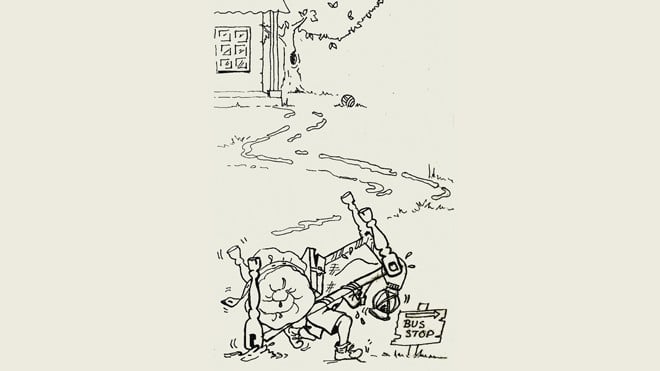

One Saturday, I packed my stuff -- the trunk, the bedding, the laaltain, and the charpai -- yes, the charpai, too -- and left for the weekend. I don’t remember how, but I managed to cart all my stuff to the bus stop and boarded a bus to Dadar, my home, 19 miles away.

I hadn’t informed anyone at the boardinghouse that I was going home for the weekend. I didn’t know if it was required. Nor did I know that I was not supposed to take my charpaai and bedding with me when I went away for the weekend.

My parents were surprised to see me back with all my stuff, but they didn’t seem to be too alarmed. In fact, my mother’s face lit up with delight. She greeted me with her usual "Wow, my Aziz is here!" and started the feast almost immediately. I ate greedily for the next two days, at breakfast, lunch and supper -- and in between. I wished the weekend could last forever. But it didn’t. I had to go back to the boardinghouse on Monday, with all the stuff that I had carried with me. I felt miserable at the thought of returning. Even a bagful of fresh homemade cookies couldn’t lighten my mood.

My roommates, assuming that I had fled the school, were astonished to see me back, as if I were a runaway prisoner returning voluntarily to my cell. Right away, I was ushered into Sahib Shah Master’s office. I was petrified.

"Why did you run away?" Sahib Shah Master thundered. I told him as convincingly as a frightened 12-year old could that I hadn’t run away; that I had gone home just for the weekend; that I didn’t know I was supposed to ask for permission before leaving. I also explained why I had taken the charpai with me -- I was afraid it might be stolen.

For some mysterious reasons, Sahib Shah Master didn’t bring out the stick. He simply dismissed me with a warning not to leave the boardinghouse again without permission.

‘Never!’ he thundered again. He had probably read the panic in my eyes and didn’t want to make it worse; or perhaps my terrified appearance touched a soft spot somewhere in the deep recesses of his heart that we didn’t know about. Or, more likely, in his books, going home without permission was not as big a crime as loitering in the bazaar or not getting up for fajar prayers.