Santokh Singh Dhir’s delightful short stories are tinged with music and humour

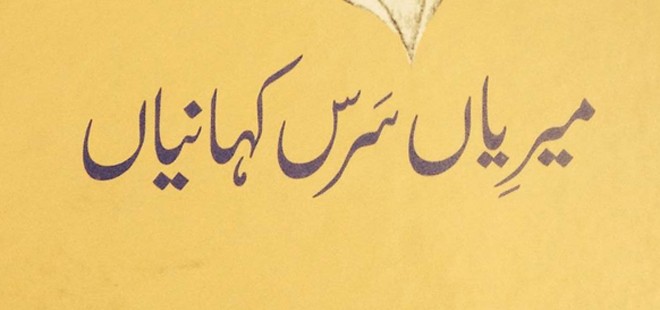

Santokh Singh Dhir’s Merian Saras Kahaniyan is a delightful little book. Through the phrase ‘a delightful little book’, I mean to suggest that the book’s strongest point is its language, which is tinged with music and humour. The rustic and rooted Punjabi of the book belongs to a part of Punjab that the author knows well, where the toll of standardisation or tyranny of Hindi/Urdu has been kept at bay.

At the beginning of the book, Dhir tells the reader that the selected stories in the book are one-third of his total output. It would have helped if the indefatigable Maqsood Saqib, the publisher, had also provided an introduction of Dhir, to place him within the context of modern Punjabi literature, along with a list of his entire corpus.

By and large, all the stories delight the reader not just in encountering Dhir’s thoughts and insights but also when his various characters engage in conversations. To both the initiated and otherwise, comprehending what is written on the paper could be a challenge. But that’s exactly what is pleasurable about his work.

To read Dhir’s prose is to hear it first and then transmit it back to the visual experience. Reading him brings to mind some of Asad Mohammad Khan’s short stories, such as ‘Narbada’, which also delight the reader when his diction and characters find themselves traversing rustic terrains.

Unlike Khan, who keeps a wide canvas and experiments with narrative techniques, Dhir’s stories do not travel beyond the time frame in which the stories were written. His thematically restricted stories mostly end up examining the clash between humanity and inhumanity, without focusing too much on external forces at play. For example, in the short story, ‘Do Chitthiyan’, an old woman asks the narrator, a young man in their village, several times to read the letters sent to her by her son who is a soldier fighting in World War II.

There are in fact more than two letters, one of the two letters brings the news of the soldier’s death. The earlier letter is written in a humorous mix of Punjabi and Urdu, and Dhir does such a wonderful job at creating a mongrel speech -- which the narrator calls "na urdu, na punjabi, te hai sabho kutch - pata na’in kehri boli si par mein aus nun fauji boli keh sakda haa," -- that when news of the soldier’s death arrives, it has very little impact. Here’s a sample:

Though one can deduce some critique of war and colonialism, it is buried under the charming simplicity of village folks and the accidental humour that their lives throw up.

Dhir’s tight focus on language reminds us of African-American writers who have, since a long time, created one of the richest bodies of literature that go against the grain of standard English by Caucasian writers. I recently happened to read Cane, a classic, by Jean Toomer who penned only one book and then disappeared. Written in 1923, it is a highly experimental novel, both in terms of language and structure. Each chapter is a stand-alone, but together they stand as testimony to the collective pain of the African-American people. A few chapters are simply short poems. Some of the dialogues are witty. Here’s one example:

"He shoved his big fists in his overalls, grinned and started to move off.

"Youall want me, Tom?"

"Thats what us wants, sho, Louisa."

"Well, here I am-"

"An here I is, but that aint ahelpin none, all the same."

"You wanted to say something? . .."

"I did that, sho. But words is like the spots on dice: no matter how y fumbles em, there’s times when they jes wont come. I dunno why. Seems like th love I feels fo yo done stole my tongue.""

But Toomer’s characters appear full of deep anger, which is missing from Dhir’s writing.

There is very little room for feminist or Marxist excavation of the human landscape. One of the earliest stories Dhir wrote about the tragedy of 1947 partition ‘Mera jrya gwandhi’, revolves around a lone Sikh as he spots his close friend and neighbour and few of his surviving relatives in a caravan of uprooted refugees on their way to the newly created country. The story is about their neighbourly love for each other. The author describes how the girls perform chores together and the boys look after each other’s crops and animals, without any regard for religious differences. This serves to remind us of a way of life that is now difficult to imagine. Such details dispel the myth that people in pre-partition India lived as separate religious communities in Punjab’s rural setting.

Other stories are more complex in terms of how Dhir examines relationships among various communities who have lived in Punjabi villages for a long, long time. Whether it is strength or a weakness, there are no villains in his stories, only temporary shortcomings.

All in all, one should be thankful for books written in Punjabi now available to readers in Pakistan. Maqsood Saqib has done a superb job producing this fine looking book, completely free of typos. Such books build our faith in shared humanity.