Listening to the fascinating tale of the longest serving commandant of Chitral Scouts, known for his association with the Afghan jihad, who has become a mythical figure in the area

The Colonel left the Commandant’s House at the small town of Darosh in Chitral District in the evening, presumably for the last time. He was headed for Peshawar to attend his farewell dinner which was planned for the next evening at Bala-Hisar Fort, the headquarters of Frontier Corps.

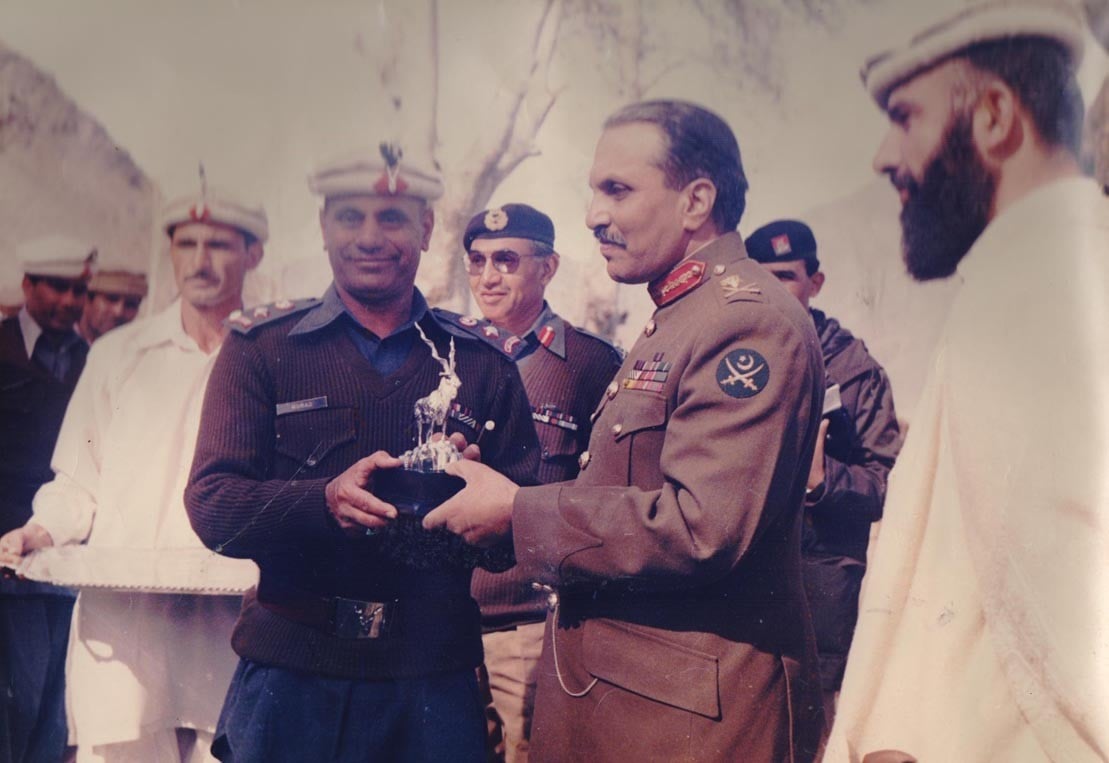

The next day was his last in service and the dinner thus arranged was to honour him. A few eulogising speeches, a shield, handshakes and then he would pass into oblivion.

The sentry on evening duty at the Commandant’s House was astounded to see the headlights of the approaching jeep. Unexpectedly, the Colonel had returned soon after he left home. He parked the jeep and let the driver retire for the day.

The sentry wondered at the changed plan. Now the Colonel would not be able to make it to his farewell dinner in Peshawar, even if he leaves at dawn the next day. But it was not the sentry’s business to question the travel itinerary of his commander and so he kept wondering.

Close to midnight, he saw the silhouette of the Colonel strolling in the lawn with his dogs. Twice he paused, patted his dogs, looked up towards the heaven and murmured something in an inaudible tone. After a while, he walked past the sentry, asked him to tie up the dogs and went inside the house.

Soon after morning prayers, his close friend Khursheed Ali, a Darosh non-military local, rushed to the Commandant House on the urgent call from the major stationed in Darosh. The officers of FC and the police SHO were waiting for him. The eerie silence was broken by the worried major who asked the sentry to break open the Colonel’s bedroom door which was bolted from inside. There he was, lying on the bed with a pistol dangling loosely in his hand.

On the table was a small note which explained how his private possession was to be distributed among the people he cared most. Among them was Khursheed Ali who got the two dogs to look after, while all other pets (including his favourite Markhor), photographs, furniture and belongings were willed to the FC Mess. He left some money for the sentry; the rest, after expenditure on his funeral service, went to his brother.

Though the short note did indicate a few things, it could not explain ‘why’ he did what he did!

On August 3, 1989, as per his wishes, he was buried in the shade of a Chinar tree which lay across the Commandant House, in a small ground purchased by the Colonel in his lifetime. Thousands of people descended from the valleys of Chitral, including the Kafirs, to attend his funeral. A smartly turned out contingent of FC, with misty eyes, fired a volley of shots in the air.

Thus ended the story of Colonel Murad Khan, the longest serving Commandant of Chitral Scouts, who lies buried in Darosh.

I first heard about Colonel Murad in November 2013 while having tea in the office of my friend Major General (now Lt General) Ghayur Mahmood at Bala Hisar Fort. I was recently posted in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as Secretary Excise and Taxation and was assigned additional responsibilities by the government to look after the Chitral district.

The same week I crossed the torturous Lowari pass and descended into Darosh, a town 40 kilometres short of Chitral. The whole bazaar seems to be buzzing with stories about the Colonel.

My friend Khalid, an excellent polo player, took me to Reshun village some 50kms beyond Chitral on the road leading to Shandur. There we met a short and muscular retired Havaldar of Chitral Scouts. Sher Ali in his heydays was also a great polo player and had represented Chitral umpteen times in the famous Shandur Mela. In 1980, Col Murad had spotted him at Shandur and offered him a job in Chitral Scouts as a sowar. The job raised the social status of the polo player and ended in a steaming affair with a girl whose rich father refused to accept him in his household.

That year, a dejected Sher Ali dropped out of the polo team, and his travails reached the Colonel’s ears. Next morning the Colonel made him ‘sit next to him’, drove the jeep at a furious pace, followed by a detachment of scouts in other vehicles and in three hours reached his village. The girl’s father fearing arrest escaped in the mountains.

The Colonel cajoled the village elders that they must prevail upon the girl’s parents to agree to this match. Overwhelmed by this unexpected response, the girl’s parents agreed. A month later, the knot was tied with much fanfare. The bridegroom and his entourage entered the village led by Chitral Scouts bagpipe band playing ‘….Jolly Good Fellow……..’

Geoffrey Moorhouse, a travel writer, historian and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and Royal Society of Literature, had also met Colonel Murad in Chitral. In his book To The Frontier (p 1984) he had described the Colonel as a shy, bald, stocky man who smiled appealingly but never laughed and offered his opinion only when asked.

Murad invited Moorhouse for lunch at the officer’s mess in Chitral which the latter compared with the club house of golf course in the home counties of England. The Colonel smilingly pointed towards an obelisk at the mess which read: ‘this stone was well and truly laid by Bonzo, Boob and Henry, July 1934’ and added "there’s supposed to be a bottle of Johnny Walker buried under there. One of our regimental heirlooms, I suppose."

Later, on the Colonel’s invitation, Moorhouse visited Chitral Scout’s headquarters at Darosh where he showed him his pet Markhor, a ridge which marked the Durand Line, Christmas cards from old British officers of the regiment and other memorabilia. What impressed Moorhouse most was his knowledge about the Afghan jihad across the border and that he "made study of Chitral his great pastime since he was posted here". The Colonel was very proud of his troops whom he always referred as ‘my boys’.

Moorhouse was admiringly introduced to the Colonel in 1983 by Rauf Yousefani, then SP Police in Chitral as someone who should "have been a Brigadier by now if he had played his cards properly. But he seems quite happy to finish his time here. He’ll be retiring soon."

However, he proved the pundits wrong by becoming the longest serving commandant of Chitral scouts. His popularity among the masses and knowledge of the terrain made him almost indispensable for the modern Great Game defined as Afghan jihad. His fame grew beyond Lowari pass down to the GHQ in Rawalpindi and was given extensions in service twice by General Zia, something unheard of in Army.

I met Khursheed Ali at his residence in Darosh. In the early 1980s, Ali was an ‘angry young’ reformer who was made the member of Zia’s Majlis-e-Shoora. He was the closest friend of the old Colonel and fondly narrated anecdotes of bygone era.

Once in 1980, when the Afghan war was at its height, a Russian plane came strafing over the mess while they were sipping tea in the lawn. "All of us dived for cover, but ‘our’ Colonel kept calmly sitting on the chair smoking his cigarette." Colonel Sahab used to resolve domestic and property disputes of the people of Chitral, helped them in getting education, organising sports tournaments and finding jobs for the deserving ones. Sher Ali was one of the many beneficiaries of his benevolence. Every family in Chitral owned him; that explained his fame and popularity in the valleys.

Both the friends were close to Zia who would give them preferential treatment whenever he visited Chitral.

The plane crash of General Zia is said to have brought down curtain on the Colonel’s career. In 1989, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto visited Chiral to witness the famous Shandhur Festival where polo is fiercely contested between Chitral and Gilgit. After the match, she was ushered to the Chitral Scouts Mess for refreshments. Lo and behold, she was greeted by a large size portrait of General Zia which adorned the wall of the main hall, still smiling under his greasy moustaches.

Bhutto was known to be magnanimous in such matters and hardly took any notice of this slip. However, there were people in her entourage who were more loyal than others. As the story goes, the then interior minister took the Colonel aside and gave him some sure tips about ‘royal’ protocol.

In Chitral, I was repeatedly told this incident was the pretext used for denying Colonel Murad further extension of service which he desperately desired. Khursheed Ali, his closet friend, however opined that though Colonel Murad had shared with him his desire for another extension, he knew deep down that his wish was like the proverbial wild horse. Army discipline discourages extensions of any sort. He had already created a record of getting two against the backdrop of the neo ‘Great Game’, but with the Afghan issue almost settled, the usefulness of Colonel Murad had also dwindled to the lowest ebb. In the post-Zia era, the new army chief hardly knew about the Colonel’s exploits in Chitral. The die was cast.

Four months before his retirement, while gossiping with his close circle as to why people commit suicide, he casually inquired from the local doctor the easiest mode of committing it. Then he placed his hand above his ears and gently moved his middle finger as if he was pulling the trigger. "He winked at us and the room echoed with laughter!" Kursheed Ali realised the significance of this act a little too late.

Colonel Murad was a confirmed bachelor who had not maintained any links with his family. In his ten years at Darosh, he was twice visited by one of his brothers; he never availed leave for a single day. His trips to the FC Headquarters in Peshawar were short and he would not stay for an extra night outside Chitral. "This was his home and we were his family. So he wanted to stay here forever."

I wanted to know more about Colonel’s family. It took me six months and more visits to Khursheed Sahab’s home in Darosh to pick up pieces of jigsaw puzzle. The Colonel, a handsome lad in his village, had fallen in love with his cousin. But before the match could be formalised, he had joined the army and the two kept exchanging letters. However, their stars were crossed. Unable to cope with the situation, he quietly left home but told his mother he would never come back home again.

A year after the Colonel died, Khursheed Ali was called by the Scout officers to meet a relative of the old Colonel. He found an old woman (the mother) bent over the Colonel’s grave, wailing and murmuring in Potohari Punjabi -- "Oh Murada, tain apni zid puri ker ditti (you stuck to your words)!"

As you descend from the Lowari pass and drive past the town of Darosh towards Chitral, do stop for a while in the bazaar. At some roadside inn, while sipping the hot milky tea, somebody would turn around to narrate the story of our old Colonel.