The events that led to dismissal of Benazir Bhutto’s governments and the consequent lessons for politicians

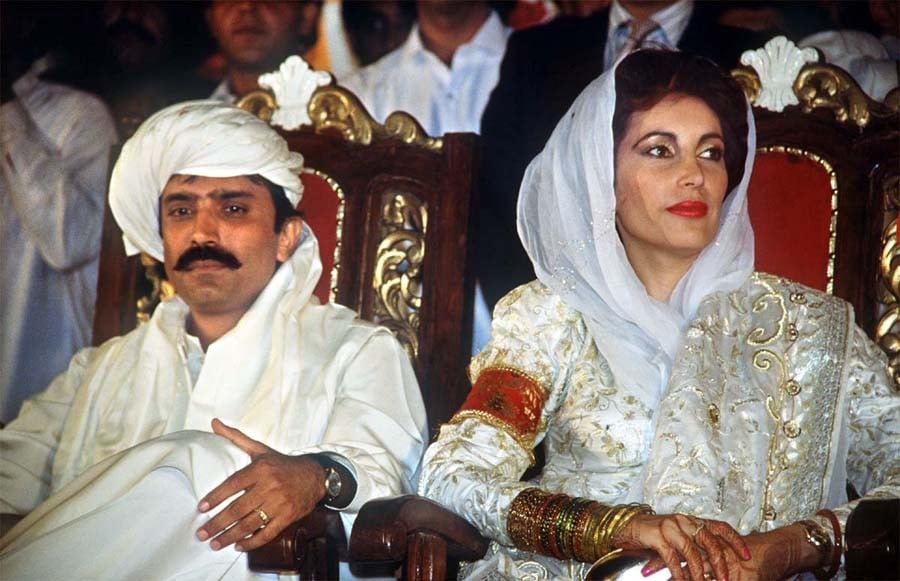

This November it has been exactly 20 years since Benazir Bhutto lost her second term as prime minister when her own handpicked president, Sardar Farooq Leghari, aborted her tenure after just three years in office. Twenty years is a long time; long enough to raise a new generation of politicians. But when you look at the events leading to her dismissal in 1996, and the years after that, you realise that though there are lessons that some politicians have learned, there is a new crop of politicians trying to reenact the same drama.

To get a clear picture of that period we need to remember that Benazir Bhutto herself had been a victim of highhandedness not only by the civil and military bureaucracy but also by the judiciary. She had lost her father because of a sordid collusion by these forces and had been deprived of her true victory in elections by the self-appointed custodians of national interest. Her terminated premiership in 1990 and ensuing demonisation by the state machinery led by Ghulam Ishaq Khan and Nawaz Sharif had left her bitter and vengeful to seek retribution.

From 1990 to 1993, she led a relentless campaign to reclaim what was her due. When the relations between then president Ghulam Ishaq Khan (GIK) and Premier Nawaz Sharif started fraying, Benazir played her cards well. Irreconcilable differences between GIK and Sharif had led to their departures and Benazir came to power after winning elections in October 1993. The three years from 1993 to 1996 were replete with efforts to save herself against onslaughts originating from her family, her party, her chief justice, her president, and of course her traditional opposition such as the Muslim League of Nawaz Sharif and Jamaat-e-Islami led by Qazi Hussain Ahmad.

If you compare today’s political situation with the mid-1990s, the most important lesson that the PPP and the PML-N appear to have learned is not interfering in the matters of provincial governments. You may argue that in Sindh and Balochistan the provincial governments are helpless in front of the federal agencies such as the Rangers and the Frontier Constabulary (FC). But the political government in Islamabad itself seems to be at the mercy of the security establishment and is pushed to the corner where there is little room for manoeuver in favour of the provincial governments.

In 1993, at the provincial level, Benazir Bhutto had her government only in Sindh. In Punjab, the PPP had 94 seats as opposed to 106 won by the PML-N. With this result, the PML-N had every right to form the provincial government in Punjab; but Benazir had had enough of a hostile PML-N government in Punjab from 1988 to 1990. She knew that this time around an opposition government in Punjab would be even more ferocious, after Benazir was instrumental with GIK in ousting Nawaz Sharif from the centre.

The PML-J led by Manzoor Wattoo had won 18 provincial seats in Punjab and the only way to keep Nawaz away from the Punjab government was a coalition between the PPP and PML-J. Benazir went for this option by surrendering the chief-minister job to Wattoo. From 1993 to 1996, for two years Manzoor Wattoo had to be pampered by the PPP leadership but when his tantrums became a bit too much -- after a brief interregnum of the governor’s rule -- the PPP selected Sardar Arif Nakai, another PML-J major leader, as the CM, a totally unsavoury replacement.

For three years, the PPP had to rule Punjab through Wattoo (two years) and Nakai (one year) -- never having a chance to have its own CM, and never giving a chance to the PML-N to form its rightful government. In the NWFP (now KP), the PPP had won the largest number of seats i.e. 22; but the ANP with 20 and the PML-N with 16 seats deprived the PPP of its democratic right to form the government. Sabir Shah of the PML-N became the CM after defeating PPP’s Aftab Sherpao. But within four months, the PPP’s central government imposed a governor’s rule and managed to get Sherpao elected as the CM after much horse trading.

In Balochistan, the PML-N had six and the PPP just three seats. The PML-N managed to garner enough independents to form a government by offering the CM post to another independent Zulfikar Magsi who defeated Akhtar Mengal, supported by the PPP. He ruled over Balochistan for the entire three years of Benazir’s central government before the assemblies were dissolved by Farooq Leghari in November 1996. Asif Ali Zardari had repeatedly and unsuccessfully tried to form a PPP-coalition government there. In short, only Sindh and Balochistan had one CM each for three years -- Abdullah Shah of the PPP in Sindh and Zulfikar Magsi, an independent supported by the PML-N, in Balochistan.

This is quite in contrast with what the PPP and the PML-N have done to each other and to other parties during the past eight years since the restoration of democracy in 2008. During the PPP government at the centre (2008-13), the PML-N in Punjab was not hostile. Similarly, after the 2013 election the PML-N could deprive the PTI of its right to form the government in the KP, but Nawaz showed political magnanimity by declining the offer of Maulana Fazlur Rahman to form a government there. Though Nawaz may have regretted his decision after Imran proved himself to be an ingrate and a political novice.

Probably the biggest lapse on Benazir’s part was not supporting a private bill presented by the opposition in the Senate in November 1993. The bill sought to remove the Eight Amendment from the constitution. Federal law minister, Sher Afgan, brushed aside the bill by saying that the PPP government itself would present in the National Assembly a similar bill; and President Leghari asserted that there was a need for consensus on this issue. Perhaps that was the only time when the PPP could have removed the Eight Amendment and spared itself the humiliation of another dismissal by its own president.

Another problem Benazir faced came from her own brother, Mir Murtaza Bhutto, who was arrested on his arrival from the UAE in November 1993. He was in a Karachi jail when his mother, Begum Nusrat Bhutto, met him and tried to reconcile between her daughter and son by announcing that Murtaza would not claim the PPP chairmanship and won’t harm her sister’s position in anyway. Benazir herself reportedly met him but within one month after his arrival the relations between them further deteriorated when Benazir assumed the party chair by easing out her mother. Nusrat now openly sided with her son.

Murtaza Bhutto was denied release on parole on ZA Bhutto’s birthday and Begum Bhutto with her daughter-in-law, Ghinwa Bhutto, was not allowed to attend the birthday celebration on ZA Bhutto’s tomb. For the rest of Benazir’s tenure, the family dispute worsened and finally Murtaza Bhutto was assassinated in September, 1996, by the Sindh police. This was used as one of the reasons when Leghari dismissed Benazir six weeks later.

When Benazir Bhutto assumed power for the second time in 1993, not only did the provincial governments become a headache for Benazir, the opposition in the National Assembly also posed a constant threat. This time the PPP had even lesser lead over the opposition: In 1988 the lead was of 38 seats -- PPP 92, PML-N 54; in 19993 the lead was reduced to just 13 seats -- PPP 86, PML-N 73 seats. This gave the opposition a much bigger leverage to launch a campaign against the alleged corruption of the PPP government. Within 60 days after the Benazir government came to power, the PML-N presented a charge sheet alleging that the government was being run by Asif Ali Zardari.

Benazir Bhutto retaliated by forming an inspection commission to investigate the alleged embezzlements by the former premier, Nawaz Sharif. When the PPP government completed its first 100 days, the opposition released another charge sheet outlining corruption in rice exports, in reconditioned cars, in Mirage plane deals, blaming that hefty commissions were being received by Asif Ali Zardari. Another charge used by the Opposition was Benazir’s friendly tone towards India, and a ‘confession’ that Benazir in her first tenure had helped Rajiv Gandhi by sharing with him a list of Sikh rebels. Now, when Bilawal calls Nawaz Sharif a Modi friend, he reenacts the drama played against his own mother, probably without realising what he is doing.

While investigating the former chief of army staff, Mirza Aslam Beg’s shenanigans against the first Benazir government, then interior minister Naseerullah Babar, came across a conspiracy that was later known as Mehran Bank scandal. Younus Habib, the chief coordinator of Mehran Bank, paid at least two billion rupees to various individuals including Aslam Beg, Altaf Hussain, Nawaz Sharif, Jam Sadiq, Ijazul Haq, Liaquat Jatoi, and others. This revelation further aggravated the already tense relations between the government and the opposition and kept resurfacing every now and then from 1993 to 96, and then much later.

A similarity between today’s and mid-90s’ PPP governments in Sindh is that both saw a tremendous crackdown on the MQM led by Altaf Hussain. Barely six months into the Benazir’s second government, security forces initiated a massive onslaught against the mostly urban party in Sindh. The MQM’s head office was raided; senior coordination committee members such as Farooq Sattar, Kunwar Khalid Younus, and Khalid Murtaza were arrested, in addition to hundreds of other workers. Door-to-door searches were carried out.

Before the end of Benazir’s first year in power, Nawaz Sharif was already on his way to start a train journey with other opposition parties to dislodge the PPP government. From 1995 onward, then president Farooq Leghari started expressing displeasure at the way PPP was managing things. First, he returned a bill sent by the federal cabinet regarding disqualification of assembly members. Then in Dera Ghazi Khan he declared that if a government is unable to give decent education, clothing, and shelter to people, it has no right to remain in power. Then he started criticising the government for mishandling the situation in Karachi.

In 1996, the year started with a new COAS, General Jahangir Karamat, who gradually came closer to the president and started grumbling about the state of affairs in the country. So now, with the president, and the COAS, already not happy with her, Benazir invited the wrath of the Supreme Court too. In June 1994, Benazir had selected Justice Sajjad Ali Shah as the Chief Justice of Pakistan. Shah’s selection was mainly thanks to his two dissenting notes. The first was in Ahmed Tariq Rahim’s case, in which the dismissal of Benazir’s government by GIK in 1990 was challenged.

Justice Shah was one of the two dissenting judges who held that GIK’s order to dissolve the National Assembly was invalid. The second was his lone dissenting note in the Supreme Court’s decision to restore the Nawaz government in 1993. While ten judges had invalidated GIK’s order for dismissing Nawaz Sharif, Justice Shah considered it strange that on previous occasions three Sindhi prime ministers were removed but never restored; and the only Punjabi premier was being restored. Benazir, of course, liked this reasoning and bypassing Justices S S Jan, Ajmal Mian, and A Q Chaudhary, promoted Justice Shah to be the chief justice of the apex court.

Indira Gandhi had done a similar thing in the mid-1970s and the judges who were superseded had resigned; but none of the three judges in Pakistan thought it infra dig and continued their job. With her chief justice in place, the PPP government went on a spree to move the chief justices of the Lahore and Sindh High Courts to the Federal Shariat Court. Two Supreme Court judges were appointed as acting chief justices of the two high courts. Justice Abdul Hafeez Memon was first appointed the judge of the Sindh High Court and then as the judge of the Supreme Court and then as acting Chief Justice of Sindh in which capacity he served two years from April 1994 to April 1996.

Justice Ilyas was also appointed first as the Supreme Court judge and then as the acting Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court. An acting chief justice also headed the Peshawar High Court not drawn from the Supreme Court. Thus, the PPP government completed a hat trick of three high courts headed by acting chief justices, and then packed the high courts with favourite appointees. Initially, Justice Shah went along, but then started balking at things he thought harmful to judiciary, though he never deemed his own out-of-turn promotion injurious to judicial principles.

Finally, in Al-Jehad Trust v Federation of Pakistan case decided in March 1996, the Supreme Court held that judges had to be appointed in consultation with the chief justice; the acting chief justices were not allowed to suggest names for appointments and only permanent chief justices could give such advice. A Supreme Court judge was not to be appointed as an acting chief justice of high court and neither could a judge be appointed to the Federal Shariat Court without the advice from the chief justice. This infuriated Benazir and she spewed her contempt for this order.

From now on it was an open confrontation between Benazir and Justice Shah, in which the president and then COAS incrementally became opposed to the government. President Leghari set up a cell at the President’s House to receive complaints of corruption. The army warned against any attempt to be chummy with India and the usual rabble-rouser Jamaat-e-Islami led by Qazi Hussain commenced its Dharna (sit-in) movement from Lahore to be concluded in Islamabad; sounds familiar? Then 15 opposition parties launched a ‘Save Pakistan Movement’ with countrywide strikes and long marches.

Finally, President Leghari used his sword of the Eight Amendment to dismiss the second Benazir government that ultimately proved to be her last.