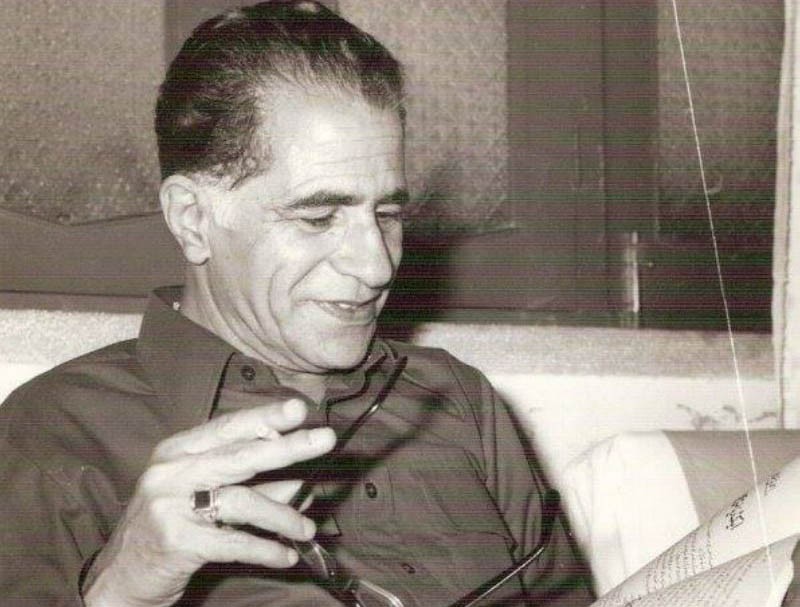

Tribute to Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi, our Renaissance man who excelled in poetry, short-stories, column-writing, journalism and a novella

2016 is being celebrated as the birth centenary year of Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi (born Nov 20), who has a justifiable claim to being our renaissance man, given that he excelled in poetry, short-stories, column-writing, journalism and a novella.

In addition, he left a legacy in terms of writers and poets whom he inspired and nurtured over the course of his long life -- Parveen Shakir, Hajra Masroor, Mansoora Ahmad, Najeeb Ahmad, Amjad Islam Amjad, Ata-ul-Haq Qasmi, etc. In these circumstances, does the fact that Qasmi was born and lived through the course of his life in undivided Punjab, thus saving him from the trauma of migration to a new homeland, count against him as a criterion of literary greatness?

2016 is also incidentally the 10th anniversary of his passing away. Why such amnesia and neglect, in his own centenary year, for a personality who was regarded as one of the greatest Urdu writers.

Qasmi was one of the most visible exponents of the Progressive Writers Association (PWA). He struck up a particularly close friendship with Saadat Hasan Manto, which is evident in the fond and frank exchange of letters between them, beginning before 1947. This continued until the decision by Qasmi as Seretary-General of the PWA to expel Manto from its fold, a decision which Qasmi regretted years later.

Qasmi’s writings form an important corpus of the battle of ideas which began soon after the birth of Pakistan, not only between conservatives and progressives on the definition and future of Pakistani culture but also within the progressive camp. Yet Qasmi, perhaps limited by his pir lineage, soon found himself at odds with the party line, whether over the expulsion of ‘renegade’ writers like Manto; or over the extent to which the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) should dominate the PWA; or even whether communism was more potent than ‘true’ Islam as an ideological weapon in order to rouse the masses for revolutionary purposes. This forcefully comes out in an exchange Qasmi had with the first Secretary-General of the CPP, Sajjad Zaheer, reproduced in Kamran Asdar Ali’s recent book on the communist movement in Pakistan, Surkh Salam.

Asdar Ali writes:

‘…Qasmi maintained that Islam and communism complemented each other and, if they were intelligently interpreted, social justice would be established in the country…The way forward, according to Qasmi, was to reinstitute the practice of ‘ijtihad’ which should reflect the needs of the majority. In this sense Islam and communism were much closer than previously thought. If, Qasmi contended, Islam can help in the eradication of the class system and communism absorbs the spiritual and moral values of Islam, then both can serve the same purpose: that of betterment of human life. If communism stood for economic welfare, then such a system could only become better if a moral code was also attached to it. Islam, according to Qasmi, provided such a code… The moral arguments of Islam and communism are the same… Within the parameters of such concerns, the issue of Islam was hence understood more as a cultural question that had to be respected if political work was to be accomplished within the masses.’

Thus Qasmi’s attempts to strike a balance between the progressives and his own proclivity towards Islam won him enemies on both sides of the ideological divide. His arrests under the Safety Act first in 1951 and then during the Ayub’s dictatorship and his apparent cavorting with the Zia-ul-Haq regime were clearly not enough to endear him to either camp.

Since much has already been written about Qasmi’s greatness as a poet and short-story writer, I want to devote attention to his lone novella or short novel Aik Rewar Aik Amboh (A Flock, A Multitude), whose publication history is as interesting as the book itself. It was first published in Qasmi’s lifetime in the journal Funoon in the 1950s in instalments, but did not generate much fanfare or critical acclaim. Then, it was posthumously included in a volume of his last fictional works, brought out in 2007, yet again unable to garner the attention it so richly deserves.

This year, the novella has finally been published as a separate volume as part of Qasmi’s centenary celebrations, with a beautiful cover done by Qasmi’s artist-granddaughter and a new title Us Rastay Par (On That Path). Although I prefer the original title, let that not detain us here from a discussion of its considerable literary merits.

In less than 50 pages, the novella manages to capture the anti-colonial struggle, the dilemma of the partition of the subcontinent and the failure of the postcolonial moment .

Qasmi is widely regarded as an eminent Urdu writer of the second half of the 20th century after the hallowed quartet of Manto, Ismat Chughtai, Krishan Chander and Rajinder Singh Bedi. He was certainly the greatest Urdu writer when he was alive. But his enduring legacy has been forgotten by critics just a decade after his death. Perhaps one major reason why this is the case is the fact that his vast oeuvre of both poetry and fiction has not been translated into English or picked up by a major Western publisher, as the work of his contemporaries like Intizar Husain was picked up.

Only two volumes of his translated stories exist, which is a gross injustice to a writer of Qasmi’s stature. The timely republication of Us Rastay Par as a separate volume and some more translations into English in his centenary year will hopefully change that. For we are all still living in the age of Qasmi.

As Qasmi himself says,

‘I light life like I do a lamp, Nadeem,

Extinguished I will be, at least I will have created morning’