Not just for the poetry, the music, and the voice, but for the entire experience that was a Leonard Cohen song

It has now become something of a cliché that when a musician of note dies, the headline normally reads ‘the day the music died’. This is in allusion to the iconic Don McLean song ‘American Pie’, which in turn refers to the 1959 plane crash that killed legendary rock and roll musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J. P. Richardson.

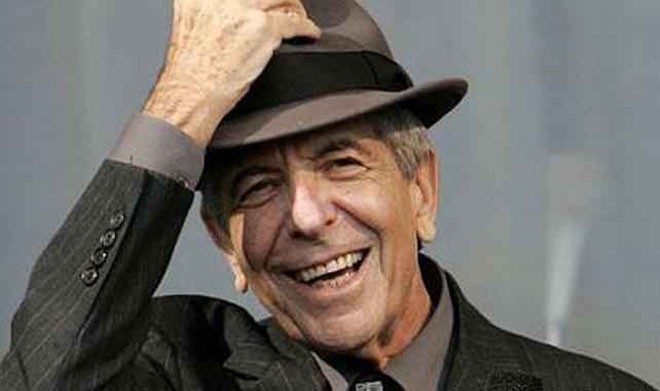

While any great artist’s passing away creates a void akin to the death of music, this title is especially apt when applied to the life and death of Leonard Cohen, who died on November 7, at the ripe, old age of 82.

Cohen’s achievement and contribution to poetry and music had recently been the subject of much adulatory debate, after singer-songwriter Bob Dylan was controversially awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. It was widely acknowledged that if music were to be finally accepted as part of mainstream, highbrow literature (about time!), Leonard Cohen deserved the Nobel before any other musician. His oeuvre includes not just some of the most popular lyrics ever written, but also some of the most moving poetry of the twentieth century.

Before he decided to expand his range to song-writing, Cohen was already established as a poet and novelist of note. His novel Beautiful Losers (1966) prompted one critic to exclaim that James Joyce was alive in the form of Cohen of Canada. This tremendous tribute, though it must have seemed exaggerated at the time, rings true today. Beautiful Losers was vilified for its radical content, but later became a defining part of the Canadian canon. Influenced by the work of W. B. Yeats, Cohen went on to become one of the most important poets of the latter half of the twentieth century.

It is a daunting task to attempt to come up with a comprehensive adjective for Cohen’s music; ‘holy’ and ‘sensual’ are two seemingly opposite words that describe his poetry and voice. Indeed, as he stood before the microphone and crooned, it seemed that he was simultaneously making love and bowing in prayer.

God, religion, sex, love, despair, hope, and politics are some of the recurrent themes in his work. He almost effortlessly negotiates the tenuous terrain where sexuality and spirituality exist simultaneously. His poetry, especially when rendered in his soulful voice that became deeper with each passing year, relentlessly juxtaposes binaries that haunt long after the music ceases to play. He is mournful and celebratory, dark and lightening, revolutionary and accepting, and all these contradictory forces came together to make him a poet sensitised by his experiences, and sensitive to the changing currents of history.

Though his music rarely entered the charts, his audience was widespread, very loyal, and continuously expanding. He was not a Michael Jackson or a Prince, pulling crowds and breaking charts. Yet, those who admired him followed his music with an almost religious fervour. At the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970, for example, an estimated 0.6 million people attended his performance.

Two of his best-known songs, ‘Suzanne’ and ‘Hallelujah’ are among the most widely covered songs in music history. ‘Hallelujah’, in particular is a hymn for the dispossessed that has been sung by an unusually high number of well-known musicians. ‘Suzanne’, meanwhile, remains one of the most poignant and potent lyrics of the twentieth century.

Read on its own, ‘Suzanne’ is a complete poem, which draws the reader in to share the heartbreak and longing of platonic love. Yet, there is also a sense of celebrating the sheer beauty of being with the lover in a way that transcends the confines of physical love. While ‘So Long, Marianne’ is evocative in its description of the loss of consummated love, ‘Suzanne’ is a more spiritual experience.

"She is wearing rags and feathers/ From Salvation Army counters/ And the sun pours down like honey/ On our lady of the harbour/ And she shows you where to look/ Among the garbage and the flowers/ There are heroes in the seaweed/ There are children in the morning" remains one of the most resonating passages of poetry from the previous century.

Politics, especially in a religious context, remains a constant refrain in his work. He was, after all, a poet in the tradition of Yeats! Among his more overtly political lyrics, there is ‘Nevermind’, a scathing comment on the complicit acts of war that we commit on a daily basis: "The story’s told/ With facts and lies/ I had a name/ But never mind" captures the devil-may-care indifference and apathy that is a part of our social fabric.

His last album, You Want It Darker was released only a few weeks before his death. It was the curtain call on a glorious music career, one that influenced such musicians as Bono of U2. It was also a great poet’s last metaphor for a life well-lived, where, to quote the title song of this last album, "There’s a lullaby for suffering/ And a paradox to blame".

With a sound that brings together influences from hymn-singing to country music, and rock-and-roll, he seduced language, his muses, and generations of fans who came not just for the poetry, the music, and the voice, but for the entire experience that was a Leonard Cohen song.

So, goodbye Leonard! I hope you are singing to Suzanne and Marianne.