There is a great need for the Christian narrative in Pakistan to be based on facts, making them legitimate citizens with equal rights

Recently, Professor Tahir Kamran, the eminent historian of the Punjab, wrote three articles on Christians in Pakistan. He narrated how they participated in the Pakistan Movement and how they have fared in the post-partition scenario in Pakistan. His articles made me think about why and how did the Christians of the Punjab support the Pakistan Movement and how they have since the creation of the country struggled to maintain (create?) a Pakistani identity.

The most oft-repeated and integral story of the Christian narrative of Pakistan is the role of Diwan Bahadur S.P. Singha in the Punjab Assembly in June 1947. Professor Tahir Kamran, in his article on Pakistani Christians elsewhere, quotes both Arch bishop Lawrence Saldanha, and Group Captain (Retd) Cecil Chaudhary -- both eminent members of the Christian community, noting the ‘critical’ contribution of Christian members of the Punjab parliament in the creation of Pakistan.

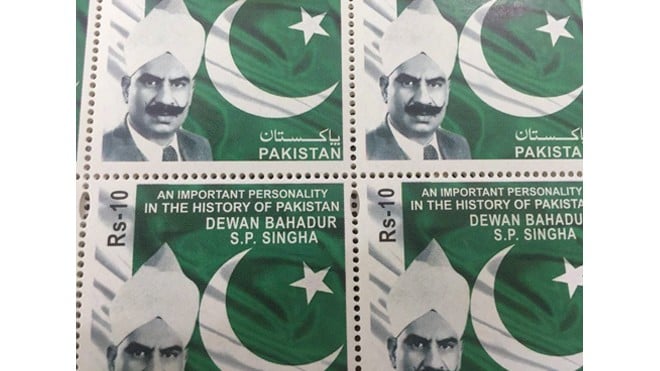

Chaudhary even mentions that S.P. Singha’s vote for Pakistan was the critical ‘casting’ vote and hence ‘created Pakistan.’ As late as April 2016, in the ceremony for the launch of a stamp in honour of S.P. Singha, it was again mentioned that his ‘casting’ vote for Pakistan was crucial in the establishment of the country. However, what actually happened was really different!

In the 1946 elections to the Punjab Assembly, two Indian Christians -- Diwan Bahadur S.P.Singha and Fazl Elahi -- were elected, and two Anglo-Indian Christians were elected, Mr C.E Gibbon and Mr P. Manuel. Out of these four members, S.P. Singha became the Speaker of the Punjab Assembly, and hence when the Punjab Assembly met on June 23, 1947 to vote on the partition of the province, Mr Singha did not actually cast his vote. The voting in the Punjab Assembly was on expected communal lines: mainly Muslim West Punjab legislators meeting under the chairmanship of the speaker voted by 69 to 27 to keep the province united, while the mainly Hindu and Sikh East Punjab members meeting under the deputy speaker rejected a united Punjab by 50 votes to 22. Hence, Punjab decided to be divided. The three Christian voting members, Fazl Elahi, C.E. Gibbon and P. Manuel, voted for a united Punjab, together with the Muslims members. That much was the reality of the situation. So why has a false, concocted story become so central to the Pakistani Christian narrative in Pakistan?

My estimation of the reason behind the perpetuation of this erroneous S.P. Singha narrative is that after partition, the Pakistani Christians (mainly Punjabi Christians), had to create a narrative to have a sense of belonging to his new country. The new country was clearly for Muslims, and was predicated on a certain notion of Islam, and hence from the outset these Christians felt that they could not be a part of it. However, if they had a decisive part in the struggle for Pakistan, they surmised, they could claim legitimate space in the new dispensation.

S.P. Singha was the most prominent member of the Christian community, and he was also the speaker of the Punjab Assembly, and so his role was mythified and presented as an integral part of the story of Pakistan. The fact that he had died in 1949 made it even more easier for an untrue narrative to be perpetuated in his memory as its false premise could never be traced back to him and since he had passed away people would not chose to tarnish the memory of the deceased man. Since then Christians and secular-minded Muslims have held fast to this ‘casting vote’ story to give a more plural and inclusive narrative to the creation of Pakistan, especially since in the first Constituent Assembly of Pakistan there was no Christian member -- in fact, no non-Muslim member from western Pakistan and so this story gave the Christians some credibility in Pakistan.

There are also two other dimensions to the Christian story in Pakistan. The first is demographic: At the time of the partition in 1947 there were just about five hundred thousand Christians in the Punjab. They were largely concentrated in the central Punjab districts, and if the Hindu and Muslim population of these districts is taken into consideration they were mainly concentrated in Muslim majority districts. Hence, demographically if the Punjab were to be divided, Christians would be mostly in the West Punjab districts, with only about 60,000 part of the eastern Punjab Hindu/Sikh majority districts. Therefore, this reality made Christians of the Punjab demographically hamstrung, as regardless what side they wanted to support, they were mainly present in Muslim majority areas.

The second factor, identified by S.P. Singha himself, was that he claimed that Christians were culturally more akin to Muslims. "Long association with Muslims had culturally Muslimised the Christians in culture and outlook," Singha claimed. He also argued that in terms of dress, economic status and beliefs, the Christians were still closer to the Muslims than the Hindus or Sikhs.

This claim of being ‘Muslimised’ was very interesting, especially since a large number of Christians in the Punjab converted mainly from Hinduism, rather than Islam and even Satya Prakash Singha -- S.P. Singha -- belonged to the same stock! Of course, the ‘untouchable’ status and treatment given to lower caste Christians was more acute among Hindus than among Muslims, but the difference here was mainly on degree and not of kind. Perhaps, the fact that most Christians came from a Hindu background made them dissociate themselves from their former religion more, in order to make the separation firmer and clearer, or perhaps the Hindu antagonism towards these converts was stronger.

Another factor could also be the fact that most Christian missionaries, largely British and American, held Islam and Muslims in higher regard, mainly due to their pre-knowledge of the religion and the fact that it was also monotheistic and had a number of similarities with Christianity. Hence, in front of two opposing religions, Christians felt more comfortable with the Muslims as compared to the Hindus.

There is a great need for the Christian narrative in Pakistan to be based on fact and so the quicker the fallacy of the S.P. Singha story is realised the better. Their nationality in Pakistan should not be dependent on the fact that their community voted for Pakistan or not, but on the simple, yet significant fact, that they hold Pakistani citizenship -- which should not discriminate on the basis of religion.

The common citizenship of Pakistan should create the sense of belonging in the Christian community rather than some concocted story of the casting vote of Mr Singha, since even without that they are part and parcel of the fabric of this country.