My first recital of classical and modern Urdu prose was held in the School of Oriental and African Studies in London in 1984. It was received enthusiastically even though I botched up two or three words.

The late Mansoor Bokhari, who was then the head of EMI in Pakistan, was in the audience. He approached me afterwards and said that EMI would like to record Faiz’s verse in my voice. I said I was willing provided EMI also let me record Ghalib’s letters. He readily agreed.

I then plunged into Ghalib’s inimitable, delectable prose. I had the good fortune of having the guidance of the great scholar-cum-writer-cum-poet, Dr Daud Rahbar who had spent six years on translating (and annotating) most of Ghalib’s letters into English. I selected two of Ghalib’s best known letters, recorded them on my modest tape recorder and posted the tape to Dr Rahbar in Boston. His reply took the wind out of my sails. In the most affectionately admonitory manner, he wrote:

"…If ever a poet had lived up to Lessing’s advice ‘write as if you are speaking’, it is Ghalib. In his letters we have exquisite specimens of Urdu conversationism. In my childhood I had the privilege of being in the company of many elders of classic personalities whose style of conversation echoed Ghalib’s culture. Please bear in mind that the letters were written by a man to whom the social graces of a life of leisure came naturally. A crisp and racy dramatic style will not do. You speak like a habitué of Hazrat Gunj "Bussab maafikeejiyay" is not Ghalib. You must not roll two words into one. Be more alert about articulation, say, ‘Bus Sahib, moaaf keejiyay.’ You cannot afford to throw away a single syllable of a word that Ghalib speaks. Your diction has to be precise and faithful to Ghalib’s culture."

Ashamed and abashed, I began to work again and after four weeks sent him a second tape. His reply was prompt: "You have now become too conscious of words. They seem to be dominating you. The words should stand like footmen in the presence of a Duke and move at his command. The words should be commanded by you, not with hauteur, but with perfect ease."

It took me the best part of a year before I thought I was ready to record "Ghalib ke Khahtoot" in three volumes. I do not mind saying that of all the creative works I have undertaken in my life, this was the one that has left me the least dissatisfied.

Could I have done this if I was not in England? I doubt it. I say this because it was in London that I had been made aware of Ghalib’s greatness. The man responsible for awakening in me a love for Ghalib was the late Raja Sahib of Mahmudabad.

I met Raja Sahib Mahmudabad through Attia Habibullah, the real name of the writer, Attia Hosain, the author of Sunlight on Broken Column. He was a frequent visitor at Attia’s flat in Chelsea, they had been family friends.

In those days - in the mid-fifties - Attia and I were the two leading actors in the BBC Urdu Service’s weekly plays. She had one of those nightingale voices which stays in your memory forever. She lived not far from my digs and I used to drop in at her Chelsea flat on weekends around midday to have cup of coffee, which I had to make myself. Not only that, I had to wash my mug, dry it, and put it back in its precise place. Attia was very particular about keeping her kitchen spick and span.

*****

When I was first introduced to Raja Sahib Mahmudabad, in Attia’s flat, I said Adab with my head bowed and my hand, thumb pressed by three fingers, raised to my chin. He responded courteously and then turned to Attia to say, "In say bhee tum gitpit, gitpit, main baat karti ho" (Do you speak to him in English as well?) It was a dig at Attiya for she always spoke to her children in English which made him wince. "Nahin nahin," she said "in say dono zabanon main bolti hoon" (I speak to him in both Urdu and English). "To aao mian baitho," he said with a warm smile.

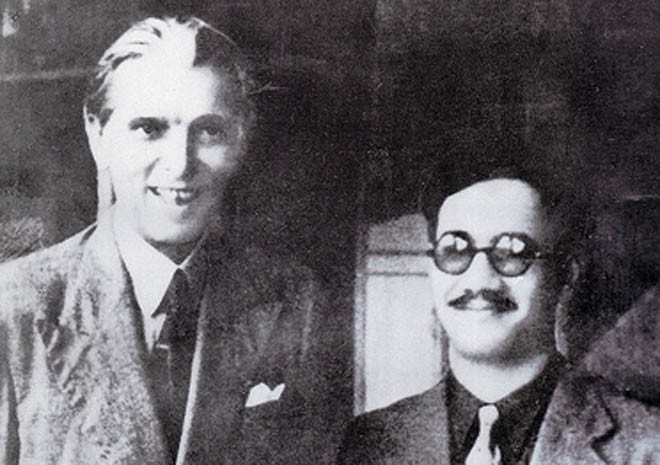

He was a short man with balding hair, a noble brow, alert eyes and a laid-back sense of humour, and exceedingly courteous. His speech was precise and extremely well-modulated. It was as though his mind had weighed every thought before uttering it. It was not just his intonation but the lilt that accompanied it which left a deep impression on me. We call it lehjay kee loch. I can’t translate it. Mellifluous is the only word that comes to mind.

I learned from him that Ghalib had written a masnavi in Urdu when he was nine-years-old. Ghalib had forgotten its existence but much later in life when it was shown to him (by a man called, Kannahya Lal, who had preserved it) he read it with great delight. Obliviously, Raja Sahib told me, whatever Ghalib had written at such a young age must have been of sufficient merit because Nawab Hussain-ud-Dawlah took some of young Ghalib’s couplets and showed them to the great poet, Mir Taqi Mir. Mir was known not only for his poetic genius but also for his acerbic temper and his contemptuous dismissal of anything but the best poetry. On reading the couplets Mir’s comment was that under the guidance of a good Ustad the boy could become a great poet; otherwise he would write rubbish.

Raja Sahib was also an excellent cook. Knowing that Attia didn’t like a mess in her kitchen, he would cook something simple like Maash kee Daal to be accompanied by a chutney made with aubergines. It is now more than sixty years since I ate that chutney but I still remember its divine taste. Even thinking of it makes my mouth water.

I once asked him why, when he had been so close to Jinnah, he had chosen to remain in India and not migrated to Pakistan. He took his time before saying "I had some differences with Mr. Jinnah." He said it in English (the only time he ever spoke to me in English) and then became silent. I realised that he didn’t wish to talk about the subject and so I never found out what the differences were.

I am deeply indebted to him. If it wasn’t for Raja Sahib and his company, I wouldn’t have had the conversational ability in Urdu which has stood me in good stead for many years.