The three lessons that can be drawn from the vicissitudes of Indian constitutional history in the 1970s

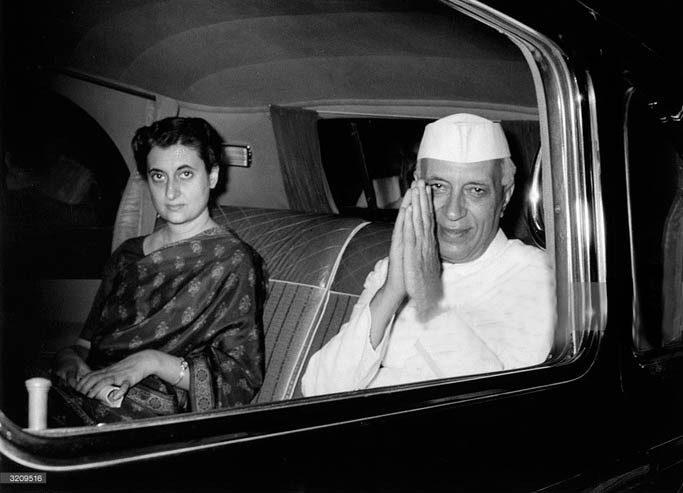

Right after the imposition of emergency in India on June 25, 1975, while Indira suspended civil liberties and introduced a mandatory birth-control programme, she also announced her 20-points agenda to liquidate debts of landless labourers and small farmers, coupled with other measures. It was like Hitler announcing his 25-point economic programme after proclaiming a state of emergency. Soon Indira detained the entire opposition, censored all the newspapers and banned all forms of political protest. The information and broadcast minister, I K Gujral, also had to quit. On July 4, four parties were banned i.e. Anad Marg, RSS, the Naxalites, and the Jamat-e-Islami-e-Hind.

In August, Indira Gandhi embarked on a journey of rapid constitutional overhaul that would lead to her downfall within two years. The 39th amendment of the constitution of India was introduced on August 10, 1975. It placed the election of the president, vice-president, prime minister, and the speaker of the Lok Sabha beyond the scrutiny of courts irrespective of the electoral malpractice and that too retrospectively. The Supreme Court was supposed to start hearing the case concerning the setting aside of Gandhi’s election on the grounds of corrupt electoral practices. The defeated candidate, Raj Narayan, had challenged her election.

The Allahabad High Court had found her guilty and barred her from running in future elections. Her removal from the Lok Sabha was imminent when the emergency was declared and she began her rule by decree. When the 39th amendment secured Indira’s position and prevented her removal from the Indian politics, in the next couple of months, the government suspended seven freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution of India. The life of Lok Sabha was extended by one year, allowing Indira to rule for another year without facing the people. Then she introduced three more amendments.

The 41st amendment prohibited any case, civil or criminal, being filed against the president, vice-president, prime minister or governors, not only during their term of office, but forever. That meant if somebody was a governor just for a day, they acquired immunity from legal proceedings for life. Perhaps the most devastating was the 42nd amendment that extended the initial time duration of state emergency from six months to one year; declared India a socialist and secular republic but removed all restrictions regarding the amendment powers of the parliament. Thenceforth, no amendment could be contested in any court of law in India.

Later on this provision was removed by the famous Minerva Case that reinforced the Basic-Structure Doctrine from the Keshavananda Bharti Case discussed earlier. During all this mutilation of the constitution and imprisoning of over 50,000 people, Chief Justice Ajit Nath Ray (1912 - 2010) proved to be the right-hand man of Indira Gandhi. His appointment in 1973 had superseded three senior judges of the Supreme Court and was viewed as an attack on the independence of the judiciary. This unprecedented promotion in the legal history of India had introduced an adulatory attitude towards the PM and the then Chief Justice made himself amenable to her influence. This was only to be reversed under the Morarji government.

The famous Habeas Corpus case was a major decision during A N Ray’s tenure as the Chief Justice. In Jabalpur vs Shukla, popularly known as the Habeas Corpus case in April 1976, led by A N Ray, four of the five senior most judges struck a severe blow to the rights enshrined in the constitution. Habeas Corpus literally means ‘you may have the body’ and it is a recourse in law whereby a person can report an unlawful detention before a court. The Supreme Court declared that ‘no person has any locus to move any writ petition before a high court for habeas corpus’.

Thus nobody could challenge the legality of an order of detention; nine High Courts had upheld this right but not the Supreme Court. Interestingly, all four judges who supported the government became chief justices of the Supreme Court barring just one dissenter, Justice H R Khanna who remained steadfast in that trying time and who was next in line to become the chief justice, disagreed with the majority and ultimately was deprived of his right to lead the superior court. He resigned when his junior, Justice Mirza Hameedullah Beg (1913-1988), superseded him to become the chief justice for just one year before he retired.

Through this decision, the Supreme Court in effect ordered the high courts to shut their doors to people. The lone dissenting voice of Justice Khanna to this day resonates in the halls of the Indian judiciary. Finally, after the removal of emergency by Indira Gandhi herself, the next general elections were held in March 1977; Indira Gandhi lost miserably and had to hand over power to her nemesis, Morarji Desai who had led the Janata Party to a resounding victory. The new government introduced the 44th amendment to the constitution that was passed unanimously in both houses.

This amendment undid most of the wrongs committed to the constitution by Indira just to consolidate her power. The 44th amendment to the Indian constitution has ensured that democracy will never be taken hostage for political opportunism. The readers who want to read a journalist’s account of those years may read a thin book by Khushwant Singh, Indira Returns (1980). Singh was one of those who supported the state of emergency.

So, now what are the lessons for us in this rigmarole? One may draw at least three lessons from the vicissitudes of Indian constitutional history in the 1970s.

First, the dynastic politics without strong checks and balances within the party, results in accumulation of excessive power even in a democratic setup. Experienced party leadership either succumbs to the whims of the scion, or quits and forms a new faction or party. In developing countries people have shown a tendency to ditch the senior leadership in favour of much younger leaders having a strong family name. But that lasts only for a while before people see through the dynastic sheen and start casting their votes on the basis of performance. Indira losing elections in 1977 is a case in point.

Second, state control in the name of nationalisation seldom works, if ever. In the 1970s, both Indira and Bhutto ended up enhancing the state bureaucracy rather than increasing people’s participation. The result was stagnation and red tape that hampered progress and put people at the mercy of apparatchiks. While essential services such as health, education, water and sanitation, power, infrastructure, and security should remain government’s responsibility and it should be held accountable for not managing them properly; all other sectors should only be regulated and not managed by the state.

Third, manipulating the constitution and appointing favourable judges may help temporarily but in the long run both the parliament and the courts correct themselves and prevent such adventurism and Bonapartism. The key is to allow these institutions to function independently.

Finally, it must be highlighted that India came out of this morass relative quicker than was the case in Pakistan, where an overgrown establishment never allowed the parliament and the judiciary to function on their own. While in India, the 42nd amendment was undone within two years by the 44th amendment, in Pakistan the doing and undoing of the constitution has been a regular feature and up until now some of the amendments that should have been thrown away are still haunting the people of Pakistan.