When diversity of ideas is limited to two polarised views and there is one accepted truth, it is time to voice dissent

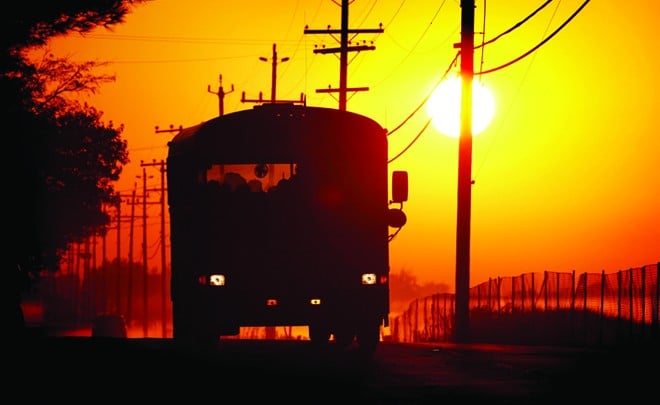

On a bus to Mullanpur

I found the bus heading to Moga parked outside the bus stop at Ludhiana, the conductor and a couple of helpers yelling for passengers. It was an inordinately hot day for late September, hot and insufferably muggy, and sweat kept on soaking shirts, its beads forming on foreheads, just as they were wiped off.

I’d broken my journey in Ludhiana and been given an amazing insider’s tour of the clock tower and the Chowra bazaar area by a man called Jeewan. He dealt with wholesale merchants for his garment factory and knew the area well. This knowledge coupled with having an eye for the romantic, for the historical, or just the whimsical, be it in architecture or cuisine made him an excellent companion and guide. Then we’d parted ways and I headed for the bus stand.

The flyover was being repaired so I had to take the longer route. As we got near the bus stop I saw that there was a long row of buses parked by the roadside. "I don’t think the buses are running today," said the auto driver. "But they were running this morning, god knows what these guys are always up to," said a rather worried looking passenger. "Why are the buses parked?" I asked.

"Dharna," I was told, "Every other day they go and sit on a damned dharna."

I didn’t get worked up because in the worst case scenario I’d have to call up my Mamoo and he would arrange for someone to pick me up. As it turned out, the buses to Patiala, and maybe also Chandigarh, had been stopped but the ones going to Moga were still running - at least for now - and I got in and took a window seat.

An old man in a worn out, white kurta pyjama entered the bus and took the seat next to me. His thick white beard was trimmed, on his head he wore a loosely wrapped turban of checkered cloth. Sweating profusely, he sat slumped, clutching a heavy-looking packet in his lap and soon the bus began to move. The air from the open windows dried the sweat on our brows and the passengers heaved a collective sigh of relief. As we left the more crowded part of town and the bus sped up, the old man turned to me: "Where are you going?" he asked. "Mullanpur," I said. He seemed visibly relieved.

"That’s where I’m going as well," he said, "So I thought I should check, just to make sure I’m not in the wrong bus. They had stopped all the buses and I didn’t know which way to go. I asked in two or three buses and then it was so hot, I just gave up and sat down by the roadside. That’s when this young man asked me what I was doing there and he put me in this bus. So I offered him money but he wouldn’t take it. There are still people like that."

He spoke quickly and softly and I leaned in, to hear better.

"But what were you doing in Ludhiana, bapuji?"

"I needed these blades for the machine," he murmured, pointing to the packet in his lap, "There’s so much fodder to be cut and … it was just pending."

Just then the bus passed some protesters holding up placards and posters. They were taking up half the road, policemen had cordoned them off using a rope. The placards displayed pictures of Modi and of Musharraf, the Musharraf pictures had crosses drawn across them. "Modi don’t meet Musharraf," said one of the signs.

"The bastards!" said the old man with sudden vitriol, eyeing them bitterly. "The s*********ers, coming and stopping the buses whenever they feel like it. What is the common man to do? Don’t we have work to do? What is one to do? M*********ers!"

The bus slowly drove around them, a little inconvenienced, but trying our best to carry on with our lives as normally as we could.

Because I must say that I disagree

There were debates raging on TV, an irate Arnab asking for Pakistani artistes to not be allowed to perform in India, and Masarji was trying his best to get Pakistan declared a terrorist state through what seemed like a signature campaign. I was constantly irked by weird messages forwarded on Whatsapp by friends, acquaintances and even relatives who I thought could reason better.

At first I thought I should just ignore them all, because it seemed foolish to retaliate. But over the weeks I found myself thinking more and more about it. I realised that the world I lived in was getting overrun by foolish ideas, like weeds taking over a plot of land, they could out-compete all other ideas, whether they be logical, emotional, true, false, or fantastical. What bothered me was that the diversity of ideas was being limited to two polarised views and it seemed that there was this one accepted truth, this one overwhelming narrative that it was morally and ethically wrong to speak against.

And I thought it was time I voiced my dissent - wrong though I may be - and thereby make my position clear; at least to myself. That does not take away the feeling that this exercise is somewhat futile and mostly preaching to the choir, for I don’t think it’ll convince anyone whose mind is already made up, and to those who see the logic behind things it’d just be saying things that seem obvious and unoriginal.

More importantly, however, I wanted to say this to anyone who wanted it said: There’s nothing wrong with not being patriotic. There’s nothing wrong with not liking the army. It’s fine to feel a connection with Pakistan.

So here goes.

War

War. For a week or so, that’s where every conversation would inevitably end up. Papa told me about the time in 1971 when he was in medical college and they would run up to the terrace to see the colourful anti-aircraft guns light up the sky. There were pictures flashed of people being evacuated along the border. "It’s the right time, the beginning of winter. This time round they might just go ahead and have a war," Uncle Dhindsa said. "It’s high time we taught them a lesson." It was an opinion that seemed to be doing the rounds. Punjab was on high alert.

Anyone who wants a war has obviously not seen one. But then that’s what books are for: there is no dearth of books - first-hand accounts; detailed, emotional memoirs; learned, well-thought-out, neatly reasoned opinions - that will tell you all you need to know. Anyone who has seen a war will tell you, in no uncertain terms, about the futility of war, the needless cruelty of it all, and how it is nothing but utter foolishness perpetrated in the name of patriotism. Anyone who says otherwise is either delusional or masochistic, or both.

What about the soldiers being killed in Kashmir then? They’ll ask. Yes, it is sad, and frustrating, and I do not have a solution. For you cannot come up with simple solutions to complicated problems stretching over decades and decades. But that does not mean you come home and beat the donkey, or vent your anger at a man who happens to be born in the territory that happens to currently fall in what is known as Pakistan. Pakistan could do nothing if all Kashmiris were happy being a part of the Indian union, so maybe there are issues other than the most obvious ones that need to be examined. But that is a question of people’s choice of government and what they consider ‘freedom’ and that is an entirely different debate.

What I do know for sure is what we ought not to do: and that is to have a full-fledged war; that I am unequivocal about.

You’re undermining the army, they’ll say. Don’t you value their sacrifices enough? I do, but then it is a job. It is work, hazardous in times of war or in areas of unrest, for sure, but work that they receive commensurate remuneration for. They are not exploited, they are not cheated, and - thankfully - no one is forced into the army. (If someone is forced to join the army because of economic constraints and would much rather be doing something else, my heart goes out to them, as to every person who’s forced to give up on his dream in order to make a living.) Any life lost in the line of duty ought to be held in highest regard; in fact, it’s hard to think of a death that isn’t to be regarded with a solemn deference.

As for the claim that they protect our freedom, it’s obvious that they do so only as long as our idea of freedom aligns with theirs, or rather that of the high command, or the power at the centre. Similarly, their protecting our lives depends wholly on the ‘enemy’ army trying to kill us. Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying that the army is redundant; it isn’t, not until there is still mistrust and hatred. But then we must strive to do away with both.

Punjab

"So is there a Punjab in Pakistan?" my wife asked me once when we were discussing Partition and how Gurdaspur almost went to Pakistan. She finds it very amusing that I could very well have been a Pakistani. "Of course there is, for Punjab was partitioned."

And then the Indian Punjab was split again in 1966, into the Hindi-speaking Himachal and Haryana, and the little triangle of Punjabi majority that we know today as Punjab. The result: there’s a province called Punjab in Pakistan that’s about four times the size of the Indian state of Punjab. It is also Pakistan’s most populous province, almost completely Muslim, and they write their Punjabi in Shahmukhi, like Urdu, and not in Gurmukhi. So much for the Sikh-Punjabi identity. The way I see it, the Sikh-Punjabi community has gone and demarcated increasingly restrictive boundaries - be they spatial or cultural - around themselves until they’re left stranded in a little, depauperate triangle, for the more we designate as the Other, the poorer we leave ourselves. And there seems to be no end to the trend, because all around us people seem to be ever ready to keep dividing and subdividing themselves in an extreme-right xenophobic frenzy.

My great grandfather was a scholar of Persian. My grandmother tells me that he topped his Giani as well as his Persian exams - something that his Persian teacher just could not believe. My grandmother is known by everyone - and I mean everyone - as Ammi or Ammiji. I asked her why, and she said she didn’t like the idea of being called mamma, so when my mother was born my grandmother asked her to call her Ammi and everyone else just followed suit. And my grandmother called her father Pitaji.

That to me is what Punjab was: a place where Persian, Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi and numerous local dialects mixed and mingled; where Sufism infused both Islam and Hinduism, and where Sikhism, like a delicate sapling, first took root; a land whose cultural diversity stretched from the Indian mainland, all the way to present-day Iran - a place that I know close to nothing about - but whose language, amongst numerous other words, gave the land its name: Punjab.

More irksome graffiti

The trouble with asking Pakistan to clean up its act before we allow Pakistani actors to perform here, or allow trade with Pakistani traders is that the actors and the traders aren’t responsible for their government, and may not even approve of their government - not any more than I do of mine. We must not confuse the people living in Pakistan with the people who control the policy in Pakistan. We may live in a democracy but honestly, how much say does the common man have over the national policy? How responsible is any Punjabi for what the Badals are doing in the state?

And if this is meant to be a strategy to arm-twist the government or the power centres, it seems rather far-fetched and implausible even to someone as politically unaware as me. Making the common man suffer to reach the policymakers is misdirected and even somewhat cruel. Moreover, such an approach would further antagonise the common man in Pakistan who - judging from the people here in India - probably think of India vaguely as an enemy mainly because of the prevalent propaganda, and would very much want to get on with their day-to-day lives.

The way forward is to highlight the things we have in common, and not through some macho, jingoistic, call to fight, kill and subdue. What we ought to be rather pushing for are better trade relations and a lot more cultural exchange with Pakistan.

There were artistes - like Bhisham Sahni, whose autobiography I just finished reading - who, after surviving Partition came to hate communalism, not Pakistan. That’s the vision we need at the moment. A common platform for literature and art and a harmonious mingling of artists, for instance, would go a long way to improve relations between the two countries. You wouldn’t consider someone who sings the same songs as you in the same language as you as very different from you, would you? And maybe it’ll be a little more difficult to want to kill someone who’s so much like you, wouldn’t it?

If this sounds like the argument of a weak-minded, weed-smoking hippy and you subscribe to the more politically aware, economically sound opinions about how the tripartite relations between China, Pakistan and India, leave India with no choice but this or that or whatever, just think of this as a devious opinion, as an imbecile’s idea of intellectual vandalism, as the irksome graffiti on the wall that you can just walk past; but it does exist.

My grandfather, my father’s father, used to work in the electricity board in Lahore before Partition. Whenever his leave ended, he’d cycle back to Lahore along the branch of the Upper Bari Doab canal that passes close to our village. That canal still exists, and I’d love to cycle the 90-odd kilometres to Lahore along it, to try and piece together from this fractured landscape, an image of the past, of the Punjab that was and that shaped the people whom I’ve heard so much about - be they famous poets and artists, or my own family.

Until that becomes possible, I’ll just keep making these occasional mumbling noises about love and Punjab and Farsi. For what can we do but try to carry on with our lives as normally as we can.