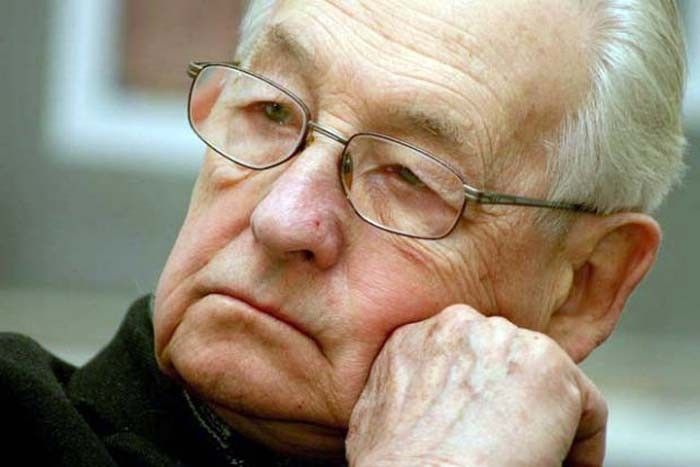

Director Andrzej Wajda created marvels that no film lover should miss

If you have seen films such The Pianist and Three Colours trilogy, you must be familiar with names such as Polanski and Kieslowski -- both directors of Polish origin. But much before these masters of moviemaking attracted world fame there was a giant of Polish cinema, Academy Award-winning Andrzej Wajda, who documented at least a century of Polish society with his camera. Wajda died on October 9, 2016 at the age of 90 and left behind works of film art that, in a way, encompass generally the entire 20th century, and particulary the Nazi and communist chapters of the Polish past.

Let’s begin with his first full-length direction in A Generation (1955). It was the opening salvo of his war-film trilogy based on a novel set in WWII. The story revolves around two young men who are petty thieves but cannot tolerate the German occupation of Poland. They carry out wayward acts of rebellion such as stealing coal from a German supply train before getting involved in an underground communist resistance cell. The film is one of the early portrayals of how relief operations were run in the Jewish ghetto during the uprising.

Since Wajda himself had been associated with the Polish resistance, the film is almost an eyewitness account. A Generation was followed by Kanal and Ashes and Diamonds completing the trilogy. Fast forward 20 years to 1975, and you find Wajda directing The Promised Land showing life in a Polish manufacturing town at the turn of the century. The film shows the ugly face of early industrialists indulging in cutthroat competition to earn profit but least bothered about the unsafe working conditions for labourers in dirty and dangerous factories which contrast sharply with their opulent residences devoid of taste and culture.

Wajda’s screen imagery reminds us of a world where Dickens, Zola, and Gorky come alive. He brings together characters of a Pole, a Jew and a German together as friends who pool their money to build a factory. With a brilliant stroke of genius, the director blows up all prejudices of nationality and religion to show their ruthless pursuit of fortune. The movie is highly critical of rampant capitalism and its characters are ever ready to take advantage of the new potential for fortune-making. A large part of The Promised Land is concerned with raising the initial capital for constructing a factory.

Today, in the 21st century, the business schools run courses on entrepreneurship and entice everyone with terms such as ‘venture capital’ and ‘seed money’. Rather, we should use The Promised Land as audiovisual aid to teach students how not to become capitalists by making a killing on the futures market as shown in the movie. Wajda highlights the lack of human compassion toward subordinates in those who recklessly seek careers. In the end, the film unmasks the illusion of good fortune by showing us the price of maintaining it: continuous struggle and even compromising morals.

The Promised Land is based on a novel by the first Polish Nobel laureate in literature, Władysław Reymont, who is best-known for his award-winning four-volume magnum opus Chłopi (the Peasants).

Then Man of Marble (1977) and Man of Iron (1981) chronicle a nation undergoing change while communism stagnates and crumbles. Shipyard strikers in Gdansk are investigated and flashbacks show actual news footage of 1968 and 1970 protests that gave birth to free unions and Solidarity. In Man of Iron, Wajda recreates events at the Gdansk shipyard of 1980 and uses journalistic probing to pierce into the lives of people affected by the ruling party’s penchant for suffocating dissent.

A planted hack sent to spy on striking workers finds herself torn between her manipulators and her country folk aspiring to overthrow the yoke of dictatorship. Rather than digging up dirt on the workers, she smells the dirty laundry of the party itself. The film is a fine depiction of the Solidarity labour movement that cracks the communist hold on Poland by winning the workers’ right to join independently as a union. The film continues the story of Wajda’s earlier film, Man of Marble by using the protagonist’s son as a young worker involved in anti-communist labour movement.

The young worker is clearly a parallel to Lech Wałęsa, the future president of Poland. How could Wajda make such a critical movie under the communist rule? Well, for 18 months there was a brief thaw in communist censorship after the formation of Solidarity in mid-1980 till its suppression in December 1981. Wajda made quick use of this relaxation to direct Man of Iron which became one his four movies that were nominated for the Academy Award for best Foreign Film. Finally, no discussion about Wajda can be satisfactorily concluded without a mention of Katyn (2007) which describes a tragedy in Polish history affecting generations.

In 1939, Poland was invaded by the Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and at the outset of WWII, a great number of Polish soldiers become victims of Hitler and Stalin’s atrocities. Katyn tells this story through the women related to the victims that were executed on Stalin’s orders in 1940. A diary kept by one of the victims reveals the horrors of the entire episode and the events unfold in a terrifying manner. In fact, Wajda’s father was one of those killed by Stalin’s agents in the Katyn massacre.

For enthusiasts interested in the history of Poland and how it was affected by the Nazis and the Soviets, Wajda has created living marvels that no film lover should miss.