Gulbaddin Hekmatyar’s latest gamble to try rapprochement with the pro-West Ghani-Abdullah government appears to be a desperate move

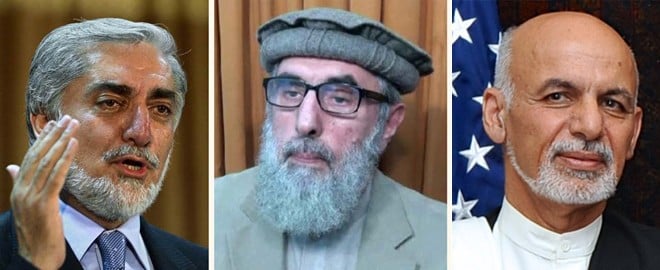

Gulbaddin Hekmatyar is known for making unlikely alliances and he has done it yet again by striking a peace deal with the Afghan unity government of President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer Dr Abdullah.

One isn’t sure how long his latest deal-making would last in view of the fact that his previous such deals fell by the wayside pretty soon.

Most of Hekmatyar’s alliances were made to come into power, though his bid to rule Afghanistan never really materialised. This time though, Hekmatyar’s Hezb-i-Islami has declared that it won’t join the Afghan government and would instead be content with becoming a part of the political mainstream after giving up fighting.

The peace agreement has been generally welcomed in Afghanistan and abroad, including by the US and its allies, as it is seen as a step towards ending the conflict and eventually stabilising war-torn Afghanistan. It certainly has symbolic importance and political significance, but there won’t be any military impact as the Hezb-i-Islami (Hekmatyar) didn’t have many fighters and was unable to launch many attacks against the US-led Nato coalition and Afghan forces.

The practical difficulties in making the agreement work were evident from the very beginning, as it was signed in Arg, the presidential palace in Kabul, in absence of Hekmatyar, who had put his signature on the document in a video clip made at an undisclosed location and later shown at the signing ceremony. He was most likely in Pakistan at the time. He couldn’t possibly travel to Kabul to join President Ghani at the ceremony until his safe passage and stay in the Afghan capital was guaranteed.

There would be hurdles galore as the two sides take steps to implement the terms of the agreement in the face of opposition by certain circles and on account of the deteriorating security situation and the occasional differences in the unity government between President Ghani and CEO Dr Abdullah.

Protests have already been staged by some political and human rights activists in Kabul and other cities against the peace agreement with Hekmatyar because they believe he should be held accountable for committing human rights abuses instead of granting him amnesty. However, Hekmatyar and his men aren’t the only ones from the past to be granted amnesty as Afghanistan’s parliament and government in the post-Taliban period have formally amnestied a number of mujahideen leaders and warlords, including some accused of serious human rights violations and killing of rivals. Most of these warlords have been part of the governments of former President Hamid Karzai and his successor Ghani. Others are members of parliament, ministers, businessmen, etc and most are fabulously rich.

A glimpse at Hekmatyar’s past makes for interesting reading. As a student of the Polytechnic Institute in Kabul, he joined Afghanistan’s fledgling Islamic movement, rose in revolt against the government of President Sardar Mohammad Daoud in the early 1970s and fled to Pakistan to escape arrest. Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto welcomed him, Ahmad Shah Masood and other Islamists to counter the Sardar Daoud government which was harbouring dissident Pakistani Pakhtun and Baloch nationalists at the time.

Ever since, Hekmatyar has been fighting different Afghan rulers ranging from Daoud to the communists Nur Mohammad Taraki, Hafizullah Amin, Babrak Karmal and Dr Najibullah, and from one set of mujahideen to another, and finally the Taliban and the US-sponsored governments led by Karzai and Ghani. It has been a long and tiring fight with no end.

During the Afghan communist rule, Hekmatyar made a deal with General Shahnawaz Tanai, who was the Afghan Army chief in President Dr Najibullah’s government and also served as defence minister, to stage a military coup in March 1990. It failed and Tanai along with his aides escaped to Pakistan in a helicopter. Hekmatyar was an Islamist and Tanai was a known member of the communist Khalq faction of the ruling People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan, but this didn’t stop them from entering into an unnatural alliance to capture power. Subsequently, both lived in Pakistan for years as Tanai became irrelevant and faded from memory, and Hekmatyar continued his struggle to stay relevant in Afghanistan’s politics and later in the post-2001 anti-US resistance movement primarily fought by the Afghan Taliban.

During the mid-1990s, Hekmatyar joined hands with the Uzbek warlord General Abdul Rasheed Dostum during the bloody battle for Kabul, which at the time was held by President Burhanuddin Rabbani and Defence Minister Ahmad Shah Masood. It was another unnatural alliance because Hekmatyar wanted to turn Afghanistan into a true Islamic state while Dostum had aligned first with the communist regime and used his ruthless militia to fight the Afghan mujahideen and then changed his loyalties to become an ally of the same mujahideen. Just like his earlier alliance with Tanai, it was obvious the one with Dostum would not have lasted long in case they had succeeded in their mission because their worldview and ideological orientation was completely different.

Eventually, he concluded a power-sharing deal with the Rabbani-Masood government to put an end to the mujahideen infighting and spare the hapless residents of Kabul of the daily barrage of rocketing of their city by the Hezb-i-Islami fighters deployed on its outskirts. Under the deal brokered by Afghan and Pakistani mediators, Hekmatyar became the Prime Minister of a barely functioning government. However, real power remained in the hands of President Rabbani and Defence Minister Masood, and before long, Hekmatyar realised how powerless he was -- and quit the government.

Hekmatyar’s choices of country with which to align also kept changing. For a long time, starting from the mid-1970s, he was aligned with Pakistan and was its valued guest in Peshawar. However, Islamabad’s subsequent closeness with the Taliban, who decisively defeated both Hekmatyar and Masood during their victorious march to Kabul in September 1996, prompted the Hezb-i-Islami’s long-time chief to shift to Iran.

He began living in Tehran, but soon found the atmosphere suffocating as he had little room to manoeuvre.

Finally, he left Iran and apparently returned to Pakistan, or to somewhere in Afghanistan as his aides claimed. Since then he has been critical of Iran. He hasn’t been as friendly with Pakistan as he was in the past because Islamabad gave more importance to the Taliban who are politically and militarily far more powerful than the fractious Hezb-i-Islami (Hekmatyar).

As all stakeholders are insisting, the peace accord was negotiated by Afghans themselves without any mediation by non-Afghans or any country or organisation. Afghan officials have in particular singled out Pakistan for having no role in making this happen as if reminding it that couldn’t bring the Taliban to the negotiations table despite promising to do so. On the surface, it is true Pakistan played no role to persuade Hekmatyar to hold peace talks with the Afghan government as he on his own was keen to do so, and these negotiations were taking place off and on for almost two years. Though some analysts have argued that Pakistan wanted Hekmatyar to become a part of the Afghan government to counter India’s strong influence in Afghanistan, this looks far-fetched because President Ghani and Dr Abdullah, obviously along with the US, wield real power and no other group or individual are capable of influencing their policies.

Hekmatyar’s latest gamble to try rapprochement with the pro-West Ghani-Abdullah government appears to be a desperate move as he had to abandon some of his known positions on issues such as the complete withdrawal of foreign forces, enforcement of Shariah, holding of fresh elections, etc to make the deal. He had vowed never to join the ‘puppet’ government in Kabul and continue fighting until all foreign soldiers left Afghanistan. None of this has been accepted in the peace agreement that has now been inked and there is no timeline when some of these things would materialise.

The deal is personally beneficial for Hekmatyar and his party, who could become part of the mainstream after years in the political wilderness. Under the terms of the agreement, a legal amnesty would be offered to Hekmatyar, who was wanted by the US and whose party, Hezb-i-Islami was classified as a terrorist organisation. Also, the names of Jezb-i-Islami members would be removed from the UN Security Council ‘black list’ and those imprisoned would be released. Hekmatyar and his supporters, including Afghan refugees linked to his party, would be resettled in Afghanistan on land and in houses to be made available by the Afghan government.

It is also possible that once back in Kabul, Hekmatyar can try and unify his fractured party by persuading its two breakaway factions that have been part of the post-2001 Afghan government to rejoin him in making Hezb-i-Islami one of the most powerful parties in the country.

The peace deal is also an achievement for the beleaguered Afghan government, which had been trying for years to take forward its peace process. Both Ghani and Abdullah had promised during the 2014 presidential election campaign to give priority to the peace process above everything else and the agreement with Hekmatyar certainly represents a breakthrough toward this goal. Though making peace with Taliban is crucial to make Afghanistan peaceful and stable and it isn’t in sight yet, the real challenge now is to implement the deal with Hekmatyar as it would send a strong message that the Afghan government isn’t powerless as the Taliban allege.