An English translation must reproduce the leisurely effect

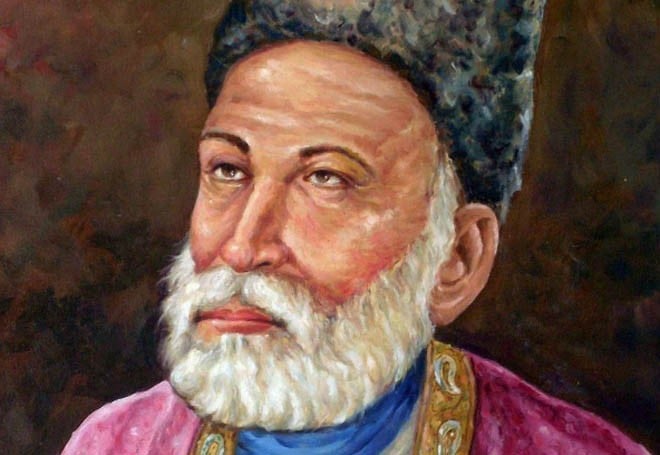

It took Daud Rahbar six years of painstaking work to complete his translation. Urdu Letters of Mirza Asadu’llah Khan Ghalib was published by the State University of New York Press. It is exhaustively annotated with notes about every idiom and metaphor, a task most necessary for readers who are not familiar with Urdu and Persian. On the first page, above Ghalib’s portrait, he wrote, "The Translation is affectionately dedicated to Zia Mohyeddin and Noon Meem Rashed." To have equated me with a poet of such eminence as Rashed, was a sign of his extreme generosity.

In the introduction, Rahbar wrote that an English translation of the letters has to reproduce the leisurely effect of the original. "In my childhood, I enjoyed the company of many elders of classic personalities; the style of whose conversation echoed Ghalib’s culture … The translation was produced without haste to ensure the right taste."

The reader can observe the simplicity and the easy conversational manner Rahbar employs in rendering Ghalib’s dry humour in a letter full of grief (but devoid of self-pity):

"Prayers from Ghalib, the man of burnt-out stars, to Munshi Habibullah Khan, whose sign is grace and whose continence, line by line, spells out felicity’s face.

Your letter arrived. My heart was gladdened by reading it. You have asked me how I am. What may I write? My fingers do not do my bidding. One eye has lost the power of sight. When some friend comes by, I shall have him write a reply this letter. They say that when someone holds the fatiha ceremony in honour of some deceased relative, the smell of the food reaches the soul of the dead. That is the kind of relationship I have with food: I smell it and that is all. Formerly, the quantity of my diet was measured in ounces; now it is a matter of grains. Formerly, my life expectancy was considered in terms of months. Now it is a matter of days. Please don’t think I am exaggerating.

* * * * *

Read also: Ghalib and his letters

Annamarie Schimmel has made an astute observation in her Foreword: "One should not be deceived", she writes, "by the ease and casualness that Ghalib’s letters seem to reveal at first sight. The reader may be reminded of the famous story of the Chinese painter who was ordered to paint a rooster and for years nothing was heard from him. Eventually, the emperor entered his study and asked for the picture. The artist took his brush, and in a few strokes he painted the most perfect rooster possible. Only then did he show the amazed emperor the thousands of sketches that were required to paint the drawing with such ease. Similar is this case to that of Ghalib and it is not in vain that he has often alluded to his poetry to the difficulty of achieving something that looks easy. The hardest work is necessary to achieve a truly artistic result. Did he not say?"

* * * * *

The uprising of 1857 had a devastating effect on Ghalib. Many of his friends and associates were killed, imprisoned and forced into exile. Others lost their home, land and financial assets. The destruction of the private libraries of Nawab Ziauddin Ahmed Khan Nayyar and Nawab Husain Mirza during the looting resulted in the irrevocable loss of his writings. Fortunately, just before the uprising he had sent a freshly prepared manuscript of his collected Urdu poetry to the ruler of Rampur, thus assuring the preservation of at least that part of his literary output.

Another terrible loss he suffered was that his pension was cut off by the British, leaving him and his family with no income of any sort. Living in a state of desolation he continued to write poetry (including panegyrics in praise of various Indian princes in the hope of gaining some financial rewards) and - so fortunate for us - exquisitely written letters to a growing number of friends and acquaintances some of whom deluged him with requests for commentary and criticism of their verse. Ghalib seldom refused a request. In fact, he was generous with his advice and always encouraged those seeking his guidance.

Maulvi Abdul Razzaq Shakir, a successful lawyer and a man of considerable literary attainments wanted Ghalib’s advice about improving his prose. Ghalib’s reply was:

"Patron Sir, your prose needs no emendation. The special prose style of yours is engaging and free of flaw. But if you want to favour me thus by imitating my style, study the Panj Ahang (Five Modulations) and other writings of mine thoroughly and diligently. Your eminence’s talents are of high calibre. Before long you will write with great excellence and will be envied by myself, my friends and foes."

Read also: Ghalib & his letters 3

* * * * *

Ghalib was particularly fond of his evening tipple. Knowing that he wasn’t able to afford this luxury every evening, his well-wishers often made it possible for him to receive his supply from time to time. Here is one of his most enchanting letters:

"Mir Mehdi, the Prosperous and Fortunate,

I had just finished the above lines when two men arrived. Not much was left of the day anyway, so I shut the stationery box and came out and sat on the takht. It became dark. Munshi Syed Ahmed Hussain was sitting on a cane stool near the head of my bed. I lay on the bed. Suddenly the sight and light of the wise and pious family, Syed Naseeruddin made his appearance. He held a whip in his hand and accompanying him was a man bearing on his head a basket covered with green grass. ‘Ah ha!’ I exclaimed, ‘what a sight, what delight! The Sultan of Scholars, Syed Maulana Sarfaraz Hussain Dehlavi, has sent supplies again’ Alas! It was not to be. The contents were other than the expected, this time, mango rather than the fruit of the vine. Ah well! This gift could not be faulted for mango fruit is equally exalted. I held each mango as a sealed decanter filled with leekor (this is how Ghalib pronounced the word liqueur) Glory be to the Maker! What marvel was involved in the filling of the decanters. Not a drop leaked out.

You are probably unfamiliar with the word leekor. It’s an English wine of fine consistency, attractive in colour and sweet to the taste. It is like a very thin syrup. You are not likely to find the word in any Persian or Urdu dictionary…"

Najat ka Talib

Ghalib"

Ghalib frequently signed himself with the words: Najat ka Talib, meaning seeker of salvation, playing on the rhyme: Talib and Ghalib.

(To be continued)