How the intersection of medicine and politics change the history of nations

Over the last few days, the health of Hillary Clinton has become a major political issue in the run up to the United States elections for president. At this time the two major party candidates for the presidency are quite old in relative terms. When elected, he or she will be the oldest or almost the oldest person to take oath as president for a first term. However, age by itself is no longer as important a factor as specific medical conditions. Based upon US statistics, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are both expected to live for another twenty years.

Considering the fact that both of these candidates are well-educated and are quite wealthy, chances are that both of them receive good medical care and look after themselves. That still does not exclude the possibility of developing some medical condition that could seriously affect their ability to govern as president. Over the last century the health of US presidents often became a serious problem. That said, during the latter part of the last century health issues rarely had any impact on the ability of the president to govern effectively.

The health of our leaders has also played a significant role in the history of Pakistan. As a physician and an occasional student of history and politics the intersection of medicine and political history has always been of interest to me. For most of my life this interest was limited to medical policy-making and its relationship with politics. Many of my articles in these pages have tackled such issues. However, the health of our leaders and the effect that has on history is at best a speculative subject but is nevertheless an interesting topic to think about.

My interest in the health of leaders and the consequences of their ill health on history were stimulated by an interesting book on the history of Tuberculosis (TB). This book came out some two decades ago. In one of the chapters about the person responsible for popularising the drug (Streptomycin) that could cure TB, an interesting factoid was mentioned just in passing. This person said that he received a letter from a physician taking care of an ‘Asian’ leader inquiring about the availability of ‘Streptomycin’. Before anything could be done about this request another letter was received a few days later saying that that the drug was no longer needed.

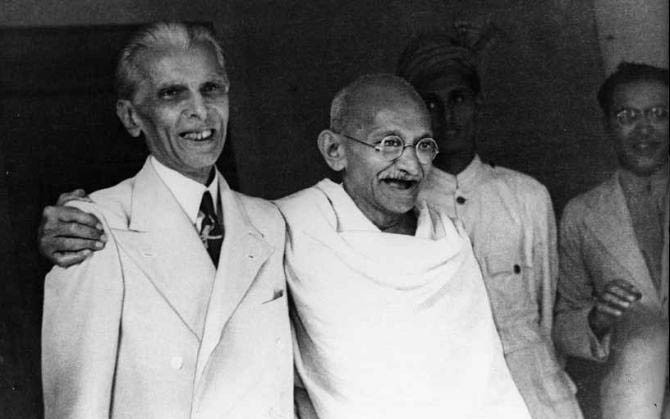

The exact dates or names of the people involved on the Asian side were never mentioned in the book. The use of Streptomycin to treat TB in humans started in the late nineteen forties. So if we put the proverbial two and two together, the most likely ‘Asian leader’ in dire need for Streptomycin at around that time would be Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder and the first Governor General of Pakistan. So as I read the book I could not but wonder if Streptomycin had become available for Jinnah, and if he had lived for at least a few more years, the history of Pakistan might indeed have been quite different.

It is a reasonable assumption that if Jinnah’s medical problems had become well known before the partition of India then the partition might have been delayed or even completely denied. And at the same time it is quite possible that Jinnah knew he was not going to last too long and therefore pushed for and accepted an early partition even though he did not get what he wanted for a future Pakistan. Even if we ignore the ‘what ifs’, the fact remains that Jinnah’s illness played an important role in the creation of Pakistan as well as in its subsequent history. Undoubtedly, Jinnah’s death within almost a year of the creation of Pakistan left the new country without a strong leader.

Ghulam Muhammad, the third governor general of Pakistan (1951-1955), though a relatively young man developed serious medical problems that affected his mental abilities during his tenure. Whether these problems (a major stroke) had anything to do with his decisions as governor general is debatable but can possibly be related. After all, his imposition of the first martial law in the history of Pakistan (1953), subsequent dismissal of Nazimuddin as Prime Minister in the same year and then the dismissal of the Constituent Assembly (1954) leading to a constitutional crisis and the famous Tamizuddin case are all actions that had unfortunate consequences for a newly-formed country. Ghulam Muhammad took a leave of absence due to ill health in 1955 and was replaced by Iskander Mirza. Ghulam Muhammad died a year later at the age of sixty one.

The next time health issues might have played a role in Pakistani history was during the late nineteen sixties. Ayub Khan as president of Pakistan faced serious political opposition in 1968-69. As a result of this opposition, Ayub Khan handed over the government to General Yahya Khan in 1969. During the last few years of his presidency, Ayub Khan was suffering from heart problems and was quite unwell. Whether his precipitous decision to resign had anything to do with his poor health is debatable. However, for a powerful ‘dictator’ like Ayub Khan to resign so suddenly does raise the question whether his poor health was responsible for his decision. Ayub Khan died five years later at the age of 66. About Yahya Khan and his rumoured medical problem (alcoholism), less said the better.

Over the last forty plus years, the health of our leaders has seemingly been of little consequence. However, Asif Zardari did suffer some medical problems during his tenure as president. These did not seem to affect his ability to fulfill his duties as president or evidently inhibit his tactical political abilities. So far in our history most of our political leaders assumed office and ran the country while they were at the most in their fifties or sixties. The only exception was of course Jinnah.

Our present prime minister is however going to be an exception for more than one reason besides his multiple tenures. If he is re-elected for a fourth term in 2018, he will be older than any previous PM and the only one known to have serious heart problems requiring major heart surgery even before starting his next term.

As a physician I strongly believe that without severe debilitating diseases and neurological problems, most political leaders can function effectively in their positions. Also at the present times most people with access to good healthcare can recover well from even major medical problems and continue to work quite well. That said the fact remains that as the age of people seeking public office increases, the voting public should know about any serious medical problems of the people they are voting for.

Finally, in the history of Pakistan more political uncertainty was engendered by the death of politicians from non-medical reasons. The assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan, the judicial murder of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the mysterious air crash that killed Ziaul Haq and the assassination of Benazir Bhutto were all unexpected occurrences that significantly changed future political trajectories and raise important and interesting ‘what if’ questions.