Another Edhi would be a miracle but fighting for his legacy need not be

For those who insist that there is life after death, the divine reward for a lifetime of devotion to God and humanity is a place in heaven. The temporal reward for pious icons who have served humanity is to enshrine or canonise them (Mother Theresa). Ironically, sainthood has a history of populist heresy. The practice of venerating departed souls and seeking intercession was usually held at the sites of graves. This custom was later coopted by the Catholic church, which then imposed stricter papacy rules and controlled the anointment of this honour.

Bureaucratising anything, including abstract things like sainthood, does not yield quick or easy results (sometime saints have been canonised after 10 centuries). Even though she was probably the world’s most recognised ‘living saint’, it took the church 19 years to anoint Mother Theresa posthumously. The cycle of the process -- from beatification to sanctification -- has to be verified by the performance of miracles. Those who experience these divine acts have to testify to the Vatican that they prayed to the virtuous nominee in heaven and of course, show proof of delivery of their claim of miracle.

In (South Asian) Islam, the closest comparative to sainthood is with reference to the sufi fraternity (tariqahs). Since there is no Islamic church, sufi mysticism and its heterodox possibilities have been much harder to harness or institutionalise. This obviously created historical tension between Islamic legal scholars/ulema, and the sufi masters.

The role of sufism in the promotion of inter-faith tolerance in South Asia has also been erroneously proposed as a liberal alternative to radical Islam in the post 9/11 years. This is contradictory to the core principle of sufism that resists instrumentalisation and nor is it in sync with any liberal politics. The reliance on fatwas and theocratic ‘solutions’ simply repeats the trend of failures in applying faith-based solutions to modern, secular challenges (like polio).

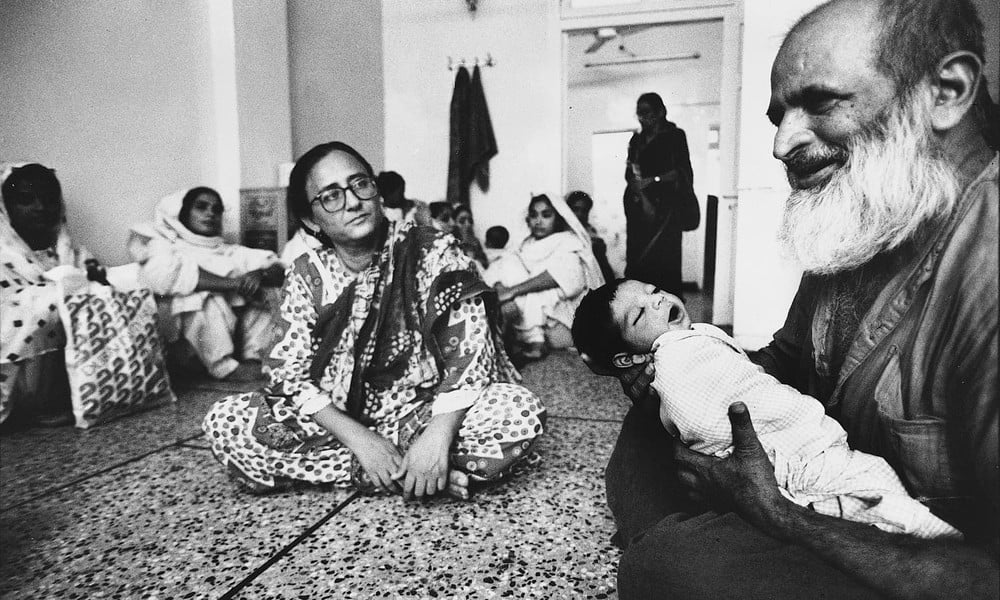

The most challenging intersection between religious and secular agendas in Muslim contexts lies in the field of philanthropy or in the service of humanity. This summer, when renowned Pakistani philanthropist Abdul Sattar Edhi died, the tributes and acknowledgements flowed in from across the political spectrum. Even the secularists, and skeptics who reject the model of charity as form of development, described Edhi as ‘a saint’. However, I propose that Edhi was neither saint nor sufi. Instead, Edhi exemplified what could be claimed as a Pakistani secularism -- a commitment that is not in the service of liberal or Westphalian principles but one that is devoted towards resisting the hegemony of an Islamic state and theocratic fraternity that discards its underclasses and discriminates against the lesser Muslims.

By all accounts, Edhi’s consciousness emerged out of his critical grasp of the multiple layers of discrimination in our society. He redressed these not through abstractions or the arrogance that seeks spiritual corrections of perceived evil. He didn’t rescue souls, just humans. He didn’t indulge in the easy self-gratifying act of giving alms, he did the dirty work of collecting them without coercion or promissories of heavenly rewards. He didn’t simply provide for the material needs of the human body, he restored some dignity into the lives that make up Pakistan’s subalterns.

Edhi also grasped how charitable communalism defines Pakistani Muslims -- the kind that may be very generous but exclusively towards its own community only. It was Edhi who knocked over the dividing lines by his inclusive and universal, not just sectarian humanity. Muslims take pride in how the Islamic ethos is committed against the ‘Hindu’ practice of female infanticide but when Pakistan’s pious populated their garbage dumps with unwanted baby girls, it was Edhi who rescued them without asking them to fill in their identities under some religion column or proof of legitimacy. For this he earned the wrath of the righteous Islamist whose career of spreading religious hate and exclusion was threatened by Edhi’s pluralism, which included serving minorities and women who carry the burdens of patriarchal social norms.

Whether one considers Edhi a saviour, soldier, saint or sufi, the best way to honour his legacy would be to return the compliment -- not through abstract prayers for his soul on this Eid but by deepening the humanity he spread in Pakistani society and making actual material contributions to his multiple causes. Better still, this would further the secular principles that he abided by in his devotion to Pakistanis regardless of his or their personal beliefs, caste, or creed.

It is important to reclaim such forms of Pakistani secularism which resist the hijacking of religion for profit and power by those who, may be pious and even charitable, take away our humanity in the exchange. Another Edhi would be a miracle but fighting for his legacy need not be.