Dr Abdul Wahab defied orders, accepted challenges and put the IBA at the top

It was 1992, the first Nawaz-Sharif government was in power and Sardar Aseff Ahmed Ali was the minister of economic affairs. The Soviet Union had disintegrated in 1991 and in the Central Asian and Caucasus regions six newly-independent Muslim-majority countries had emerged. Sardar Aseff had visited these states and offered them any assistance they needed from Pakistan. They were in need of trained professionals who could steer their countries -- from failing socialism to business-oriented economies. Pakistan offered to train officials from Central Asia in Pakistan.

The first batch of 60 officials was sent to IBA Karachi where Dr Abdul Wahab accepted the challenge of training these officials who were all fluent in Russian but could barely understand English. Never to be daunted, Dr Abdul Wahab contacted Prof Zakia Sarwar who was leading SPELT (Society of Pakistan English Language Teachers) at that time. In turn, she contacted me for help with the Russian language.

Thus began a life-long association with Dr Abdul Wahab and my eight-year teaching apprenticeship under his direct tutelage.

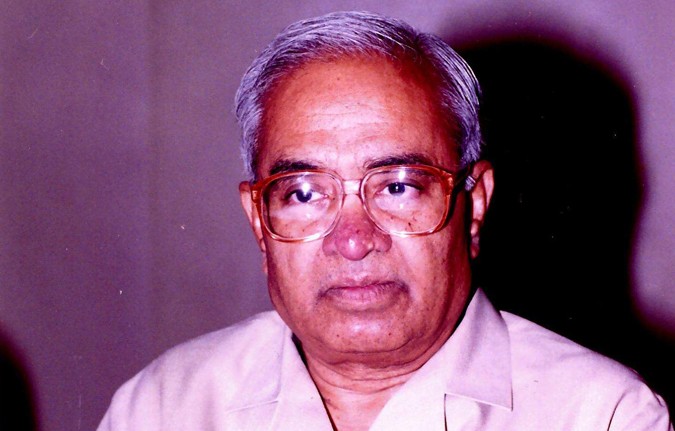

Dr Abdul Wahab who died in Karachi on September 6, 2016 was an administrator, mentor, educationist, writer, and reformer, all in one. His administration as director of IBA for over 15 years and as the vice chancellor of the University of Karachi just for two years earned him many enemies.

At the IBA, his tenure coincided with the worst ethnic nightmares in Karachi during the 1980s and 90s. Repeated curfews paralysed academic and professional lives but the IBA was one institution that stood out by not cancelling any classes even in the face of widespread disturbances all across Karachi.

Dr Abdul Wahab was mocked for his singular insistence on keeping the IBA open but he never put his students’ lives in danger; actually whenever a strike call was given, he arranged for all students and teachers to stay at the IBA overnight so that nobody had to commute while the city is closed. Sounds weird, but everybody cooperated with him; for students it was fun sleeping on mattresses especially purchased for such strikes that were common those days. His stance was simple: ‘if I allow one strike to close my institution, I will have to shut it again and again; so no compromise here.’

His mentoring skills were matchless, especially for young and junior teachers; though there were many senior teachers who didn’t like him for he was too demanding and strict and somewhat ‘over the top’; he never minced his words if he didn’t like something or somebody. Doing that he put many people off who repeatedly conspired to malign him and paint him black. When he appointed me the head of IBA’s Skills Development Unit, I proposed to him that the IBA should launch a Business English Programme; he didn’t take even an hour to decide then and there.

As an educationist, his stress on nurturing well-rounded professionals is proverbial. His IBA admission tests included substantial portion on assessing general knowledge of admission seekers; while other institutes were more interested in checking English and mathematical skills, the IBA, in addition, measured applicants’ geographical understanding of the world and their knowledge of recent history of Pakistan; add to this current world affairs and economic challenges Pakistan is facing and you have a successful IBA applicant.

Probably the IBA was the only institution that ran its own preparatory classes for aspiring candidates. Thousands of students benefitted from those classes and even those who could not clear the IBA test took away with them bundles of knowledge that they could hardly get anywhere else.

IBA’s test-management machinery became a byword for integrity and transparency, so much so that other institutions and organisations started hiring the IBA to conduct their admission tests. One remembers travelling with the IBA team led by Dr Abdul Wahab himself to Lahore, Taxila, and other cities to manage tests for thousands of students. The test papers were locked in trunks and he slept in the same room where the trunks were placed after locking the doors from inside.

As a writer he penned his ideas about organisational reforms in a recent book published in 2014. In that book he has narrated various events of his career where he was under tremendous pressure to admit certain near and dear ones of influential people but he circumvented such orders, both politely and defiantly. Luckily he had the support of almost all governors of Sindh from Jahan Dad Khan and Ashraf Tabani to Kamal Azfar and Moinuddin Haider who stood behind him when he faced pressures from feudal lords and other higher ups especially from the civil and military bureaucracy. Even Moinuddin Haider’s daughter had to attend preparatory classes before she could appear for the test.

Probably the most difficult period of his career was when he was appointed vice chancellor of the University of Karachi in 1994 during Benazir Bhutto’s second government. He accepted the challenge and started implementing the same strict and almost revolutionary policies at the university that he had successfully led at the IBA. Suddenly all hell broke loose at the university, the teachers split in his supporting and opposing groups ironically dubbed ‘Wahabis’ and ‘anti-Wahabis’.

Supporters liked the evening academic programmes that he had started on self-finance basis, for now the teachers had some additional income. Students and teachers were mobilised to clean the campus, all the classes were whitewashed, furniture improved, and fresh towels were placed in the bathrooms every hour; just as it was the practice at the IBA.

The opponents blamed him for expecting menial jobs from them.

Some didn’t like all this because it meant more work; agitation started at the campus, rumors were floated that the new VC had ‘torture camps’. In fact he had vacated university hostels for a cleanup so that unregistered occupants could be removed. Anyway, because of stiff opposition to his policies he was sent back to IBA in 1996 after just two years as the VC. His exit from IBA in 1999 was also unceremonious when the then Sindh governor, Mamnoon Hussain, appointed deputy director, Fazle Hasan, as acting director; and then handed over additional charge of IBA director to the VC of Karachi University, Dr Zafar Zaidi.

Then began a decade-long decline of IBA that deprived it of its position as the best business school in Pakistan, the coveted status since then has been occupied by LUMS. Much later, the IBA was rescued by Dr Ishrat Hussain.

After leaving IBA, Dr Abdul Wahab joined a private university as president and devoted his time and efforts whole-heartedly. He remained there until his mid-70s. Even during his last days he was an avid reader of books of all kinds. He expected his faculty members and students to remain up-to-date with the latest developments not only in their own fields but also about all happenings around the world. He never discriminated against anyone on the basis of religion and ethnic group and in that sense he was a secular and liberal person. Rest in peace Dr Saab, we will miss you.