Thirty years ago when I was in England, the EMI company of Pakistan invited me to record my selection of Ghalib’s letters in Urdu. They were recorded on 4"x 2" audio cassettes which are now considered to be out of date. In my career it was one of those few assignments I undertook which did not put me to shame.

Not so long ago, I devised a programme in which some of Ghalib’s more easily understood ghazals were to be sung interspersed with a narration of some of his letters. Before presenting the musical evening on stage, I went through the four volumes of Ghalib’s Urdu letters carefully compiled by Khalique Anjum, Professor Emeritus at Jamia Millia, Delhi. Once again a new world opened up for me

(" Wonderful is the delight of speech

When upon hearing it

One claims, "I hear what is already in my heart")

His oft-quoted, light hearted verse describes the effect that his poetry has on us.

* * * * *

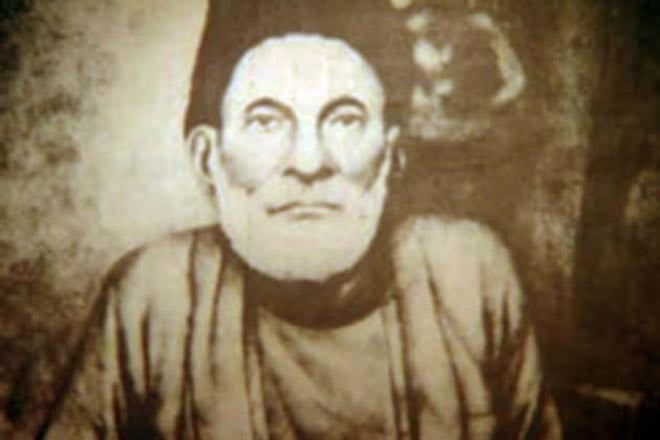

Mirza Asaddullah Khan Ghalib is, without doubt, the greatest Urdu poet of the 19th century. His verse appeals to almost every taste. We quote him more often than any other poet. There are few poets in the history of Urdu and Persian literature whose verses are as deeply filled with the whole heritage of Muslim culture as his. Behind his lines lie the wisdom, charm and the imagery of nearly a thousand years of Persian poetry, and eight hundred years of Muslim rule in the northwest of the sub-continent.

Read also: Ghalib & his letters 2

Ghalib’s Persian poetry can be traced back to the classical period of Persian poetry. He studied the Persian language intensely and, consequently, knew Persian literature better than his contemporaries. He was very proud of it and he mentions this fact, sometimes vaingloriously, in many of his letters.

But if Ghalib had been a perfect poet who applied classical model to his Persian and Urdu poetry he would not have gained that much fame and would not have captured the heart of a large part of the Urdu speaking population of Pakistan and India. His verses, despite their immense technical difficulty, lend themselves very easily to quotation since he had the gift of inserting expressions from the spoken language into his metrical scheme. In this respect, he is surprisingly modern. His Urdu poetry becomes often conversational playing with everyday language of the people around the Jamia Masjid in Delhi:

The conversationalism in Ghalib’s poetical creations is similar to the style of his letters. The lightest, and apparently superficial talk, is interspersed with the vocabulary of classical Indo-Muslim culture; even more, his most casual remarks reflect his heritage in all its different moods and shapes. The perfect ease with which he enjoys the possibility to use an Arabic, sometimes a Persian, and sometimes a proper Urdu word for one and the same object, reflects the integration of his personality within a highly composite culture.

Read also: Ghalib & his letters 3

This is best illustrated in the manner in which Ghalib plays back and forth between honorific and familiar forms of addressing his friends of different social ranks. The range is extensive and inventive. An English translation will have to grope for some devices of capturing the drama of Ghalib’s play of interchanging pronouns. For intimate friends, it was "Mr Resort", "My very life" or simply "Mian" or "Hazrat". For acquaintances, it was "Bhai" or "Qibla", but for those he wished to ingratiate, the form of his address was fresh and flowery: "Sign of Virtue and Auspices," "Resort of Those In Need", and even "Emblem of Felicity, Prince of Actuality, First and Best" etc,. etc,.

In an Urdu couplet Ghalib has joked about himself that he is not completely crazy but not completely normal either. This plurality in his character is well reflected in his letters. At one time his writing shows absolute hopelessness and then suddenly flash up in joke revealing black humour. His syntax changes from majestic to easy-going and casual, but the underlying wit is never absent. In letters that might begin with an account of his financial straits he would change gear in the next paragraph:

"Now listen to an amusing story of the day before yesterday. Hafiz Mummu was judged innocent and released a while ago. He paid his respects to the officials and petitioned for the return of his property. His claim to ownership had been verified and established. All that remained were for the orders to be issued. The day before yesterday, he presented himself at the office. His file was placed before the official who asked, "Who is Hafiz Mohammad Bakhsh? Hafiz Sahib humbly answered, "Me". Then came the question, "And who is Hafiz Mummu?" Humbly again, he answered, "Me. My real name is Mohammad Bakhsh, but I am called Mummu. That’s my nickname." The Sahib then uttered the superior words: "Well, that doesn’t make sense. Who is Hafiz Mohammad Bakhsh? You. Who is Hafiz Mummu? Again you. Everybody in the world is you. To whom shall I give the house?" The file was closed and Mian Mummu came away having lost everything."

(Translation by Daud Rahbar)

* * * * *

When Ghalib’s centenary (1969) was approaching, Mrs Bonnie Crown, the Director of Asia Literature Program of the Asia Society of New York, was eager to arrange a literary and scholarly homage to the great poet in the United States. She approached Dr Mohammad Daud Rahbar to enquire if he would like to undertake the English translation of some major work of Ghalib. He suggested to Mrs Crown ‘The Letters of Ghalib’. She agreed with enthusiasm.

The late Dr Rahbar was a polymath. He was a scholar steeped in Urdu, Persian and Arabic literature, and was fully conversant with the Western literary tradition. In the ‘Foreword’ in Dr Rahbar’s finished work, the eminent oriental scholar, Annemarie Schimmel, writes: "To translate a work of this kind which is both traditional, owing to its whole historical background, and modern, thanks to its spontaneity of style, a specialist was needed who is perfectly at ease in Indo-Muslim culture, brought up in the highly educated Muslim community of the subcontinent, as well as conversant with the technique of writing classical poetry, with Indian music, and with a way of life in which conversation on a very high level is still considered valuable. For this reason the translation of Ghalib’s letters by Dr Rahbar is an unusually fortunate event."

(To be continued)